My last post reminded me of the second post I ever made on this blog back in 2011. I didn’t know it was my second post until I just looked back and checked.

There are some prominent commentators these days, even an economist that runs a mutual fund based on his econometric analysis. The newsletter is a great read and I assume he is correct. But this reminded me of another manager that still writes great reports and is totally convincing, and as far as I’m concerned is ‘correct’.

In any case, I mention these guys in my original post back in 2011:

Perils of Trying to Time the Market

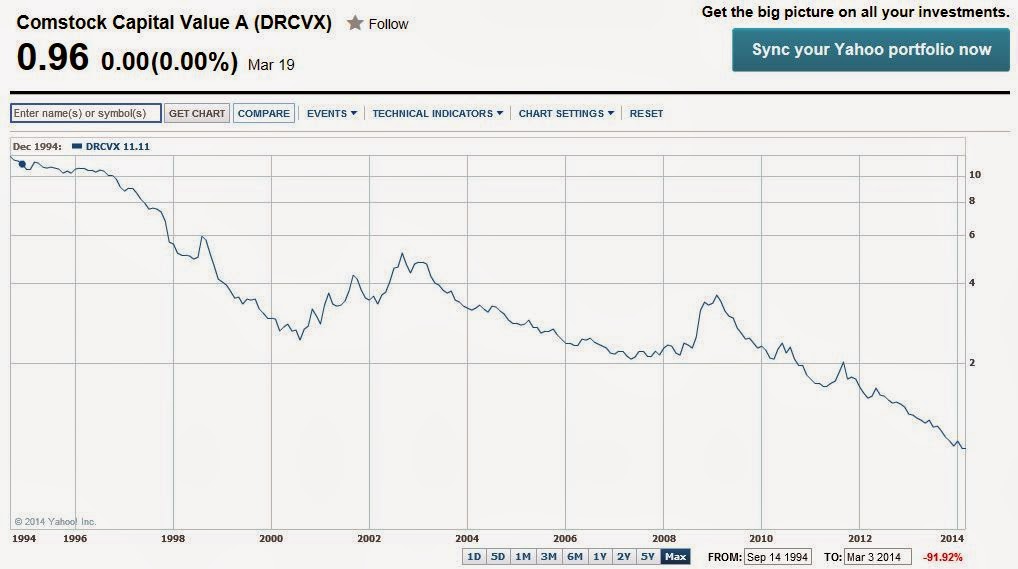

The two mutual funds I mention in the post is the Comstock Capital Value Fund (DRCVX) and the Prudent Bear Fund (BEARX). Prudent Bear also has a nice website with some scary reports. Again, the information there too is well written, convincing and scary. And they are probably correct.

But here is what those insights have done for them over the years:

Just for reference, here’s the blurb on what the Capital Value Fund is about (from their website):

Investment Philosophy & Comstock Partner Bios

Comstock’s approach is wide-ranging, including the analysis of specific equities, general stock market strategy, interest rates and real estate as well as long term macroeconomic themes centering on the interaction of inflation, debt, interest rates, economic growth and their effects on the stock, bond, commodity and currency markets. Comstock Partners started implementing these strategies when they began managing the Dreyfus Capital Value Fund (presently the Comstock Partners Capital Value Fund) in 1987 and launched the Comstock Partners Strategy Fund in 1988. In May of 2000 the Shareholders of Comstock Funds voted to join the Gabelli Family of Mutual Funds. Investment Style

Comstock Partners, Inc. analyzes economic and financial conditions from a long-term macro-economic perspective and makes adjustments based on cyclical and shorter-term considerations. In pursuit of its goals, the firm invests in various asset classes including domestic and foreign stocks, bonds, currencies and derivatives including indices and options. For the Capital Value Fund, Comstock Partners can buy or sell short and make use of leverage in order to maximize returns under various market conditions. In effect, we believe our operation resembles a modern-day hedge fund in its scope of activities.

For each of its asset classes, Comstock adheres to macro-economic themes while also utilizing a disciplined investment philosophy that attempts to remove the emotional element of investing by focusing on data that, in the past, has exhibited a correlation with an asset’s future price movement. Such data may be fundamental or technical and includes indicators relating to the economy, money and credit, valuation, price momentum and investor sentiment. While each of these indicators may provide some degree of insight into the future performance of a particular investment, Comstock believes that an appropriate combination of these tools provides the highest probability of accurate market timing and security selection. Investing, of course, inherently involves subjective judgements and there can be no assurance that Comstock’s investment approach will prove successful.

They have been bearish for as long as I’ve known about them, and it’s a little scary because even when they turned out to be right and the market collapsed after the internet bubble in 2000, their gains barely recovered losses incurred during what I’m sure they considered an irrational bull run in the 1990s. Even at the bottom of the worst financial crisis, the gains they had still barely recovered losses of earlier years.

The scary thing here is that if you read any of the reports going back in any given year you would nod along and agree with what they’re saying. Yes, too much debt, too much leverage, Fed pump priming too much etc. And yes, the housing market collapsed, the internet bubble collapsed, valuations getting high etc. And yet they weren’t able to make money on those astute insights.

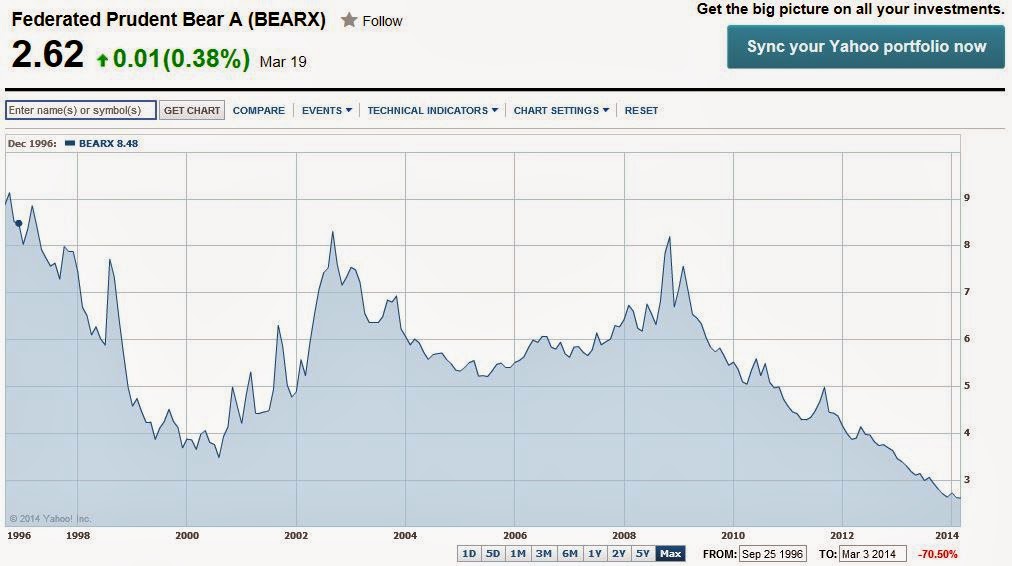

Here is another fund that was initially supposed to invest ‘prudently’. The original intent was to be short the market when the dividend yield was lower than a given level and then long when the dividend yield was higher than a certain level. I think it was 3% and 6% or something like that. But the dividend yield has never gone back up so they have been short since inception. The idea sounded good on paper.

Their website too has some very interesting reports, but again, their insight isn’t turning into profits. They couldn’t recover earlier losses even after the worst financial crisis since the great depression.

I don’t mean to pick on these guys. They seem to be honest, hard working, decent people. And these funds may serve a purpose in some portfolios; maybe people want to allocate capital to these funds as a sort of a disaster hedge. Who knows.

And I am not cherry-picking funds to make my case. I have known about these funds in real time for a very long time; I don’t know others that run their portfolios in a similar manner with long term records going back this far.

Of course there are some successful macro hedge funds, but those are different; they are more engaged in leveraged futures, bond and foreign exchange trading and other things like that so they don’t focus just on trying to call the stock market.

This is a cautionary story for people who are interested in investing in mutual funds that promise to make money in all market environments, hedge their equity or whatever. Alarm bells should go off if there is a claim that they could do that successfully over time and through cycles. And as someone once said, the bear argument is always going to be more sophisticated and smart-sounding. Listen to Buffett on his bullishness on America, for example. He just sounds pollyannaish.

(OK, I know some of you will say, but what about Fairfax/Prem Watsa?! I also tend not to like the extent of his hedging of the equity portfolio, but he has a proven track record of outperformance even including hedging. Of course I would prefer the BRK, MKL or Y model of no hedging, but Watsa has performed over time with these decisions so…)

Back to Buffett

So let’s go back to Warren Buffett for a second. He was kind enough to give us his thoughts on investing in the recent letter to shareholders.

He starts the section off with a Graham quote:

Investment is the most intelligent when it is most businesslike. -Benjamin Graham

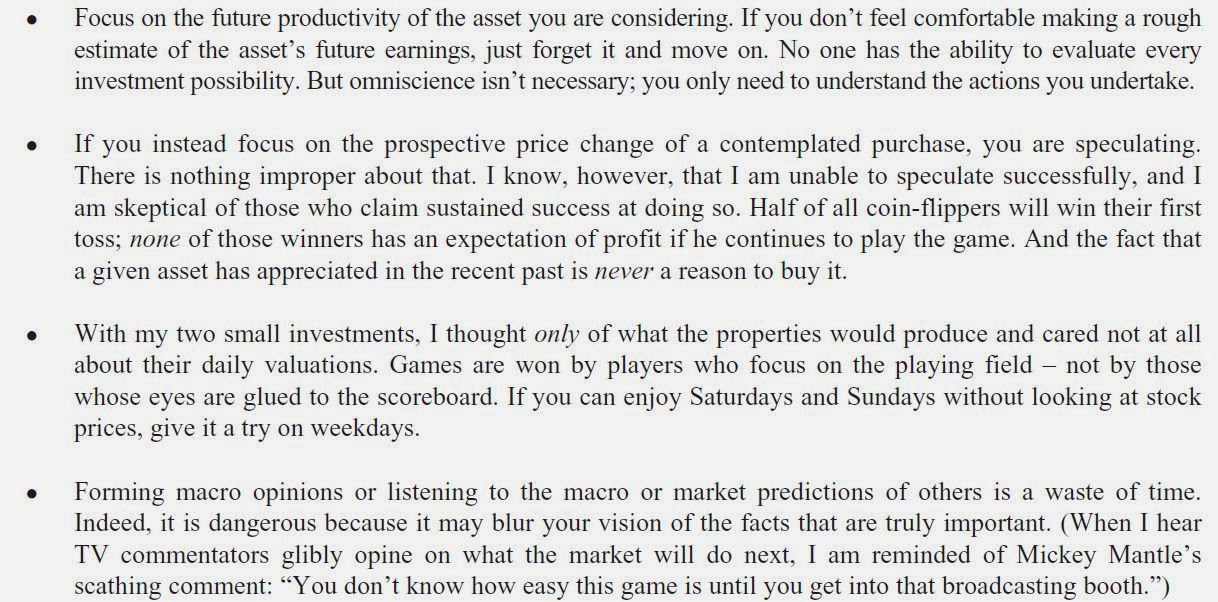

And here are some of his thoughts; what he feels are certain fundamentals of investing:

Note the second bullet point:

If you instead focus on the prospective price change of a contemplated purchase, you are speculating.

So if you are looking at the market overall p/e ratio and deciding that stocks are overvalued and they must go down, then you are speculating. Even if you are just pricing the market and getting out so that you can get back in cheaper, you are still speculating. (If something gets really expensive/overpriced, then by all means sell!)

His two purchases were in 1986 and 1993. Both were times that were considered bubble-ish. After black monday, the outlook was horrible; people called for the coming of another depression. What happened in 1987 and 1994 “was of no importance to me in making those investments”.

He says thinking about macro is a waste of time and is indeed “dangerous because it may blur your vision of the facts that are truly important“. I think the above two mutual funds are perfect examples of this danger.

As he says, “games are won by players who focus on the playing field – not by those whose eyes are glued to the scoreboard”.

Value investors shouldn’t care about the fluctuations in the market (except to the extent that they can take advantage of it); they keep their focus on the business (playing field) and not the stock price (scoreboard). The above two funds seem to focus a lot on the scoreboard, setting up positions so their profits will be based on the accuracy of their market predictions (and not on the evaluations of businesses).

Stocks Don’t Always Go Up

All of this is not to say that valuations don’t matter. They matter a lot. We are “value” investors, so of course “valuations” matter. When we say don’t worry about warnings about overvalued stocks, bears will call us perma-bulls; that we bulls think markets always go up. Well, they don’t. They will go up and down as they always have. My argument is that it’s going to be hard to predict the market based on it.

Higher valuations will mean lower prospective returns but higher valuations don’t necessarily lead to an imminent bear market or correction. A bear market or correction will always be inevitable, but it’s hard to say when it will happen. And if you don’t know when it’s going to happen, it’s going to be very hard to capitalize on it (as we see from the DRCVX and BEARX examples).

Other Alarm Bells

This goes off a little on a tangent, but I was browsing through a presentation of Brookfield Asset Management and I almost fell out of my chair. I have always thought that this alternative asset thing is getting a little bubbly. Over time, I guess it can grow as an asset class. But a lot of this movement into alternatives seem driven more by fear and seems like a kneejerk reaction to the financial crisis; people got hurt so badly in the financial crisis that they don’t want a big allocation to stocks anymore.

Also, it is driven by pension needs as interest rates are too low; they need to invest in higher return asset classes to meet their expected returns. Bond yields are too low and stocks have done nothing over the past decade.

The AUM growth at the listed private equity companies (most of which are really well run by really good people) always scared me a little bit because of this.

What happens when interest rates start to move back up? Some of these assets can get hit by a double whammy; once because capital moves out back into higher yielding bonds, and then again as cap rates go up because of higher rates (even though there is some cushion there as spreads are apparently still wide).

Anyway, first of all, I have to say that Brookfield is an amazing entity and is well run and they do have some of the best reports to read; very detailed and everything well explained. So this is not a judgement at all about Brookfield or any of it’s entities.

Here are some interesting slides.

If you look at Buffett’s third bullet point above, it says, “…the fact that a given asset has appreciated in the recent past is never a reason to buy it”.

Of course there are many good reasons to get into “real” assets but:

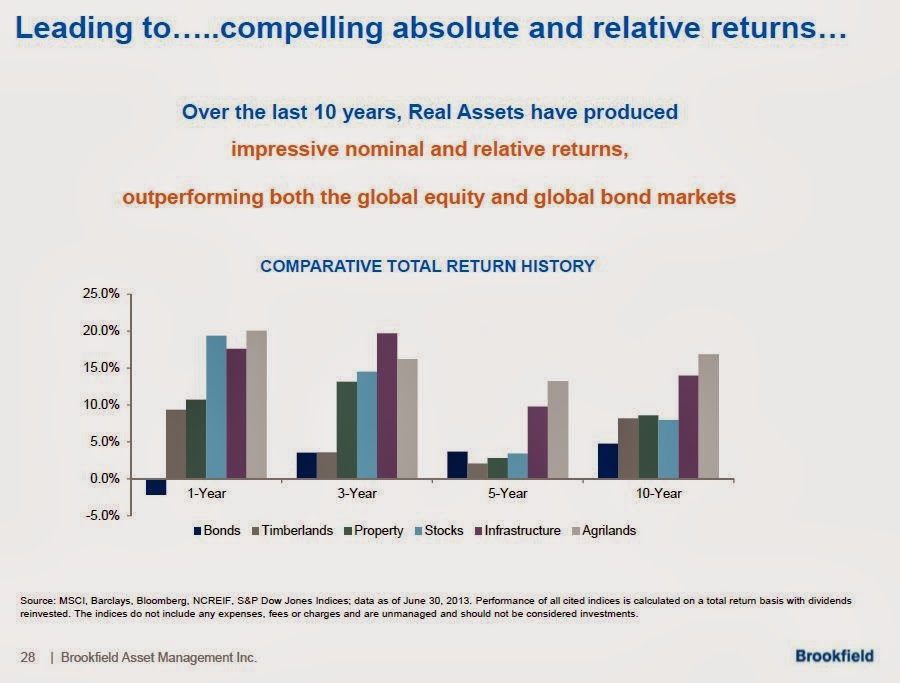

Great ten year return is good, but I’ve seen this sort of thing in the past with all sorts of asset classes. The U.S. stock market looked good on this basis back in 1999/2000 too.

And here’s the all too familiar chart and table:

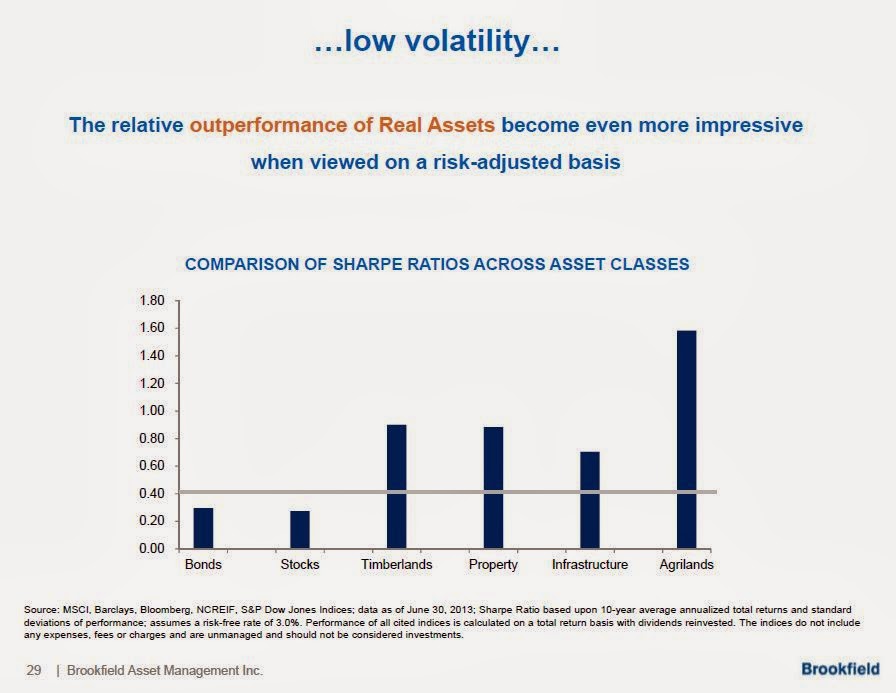

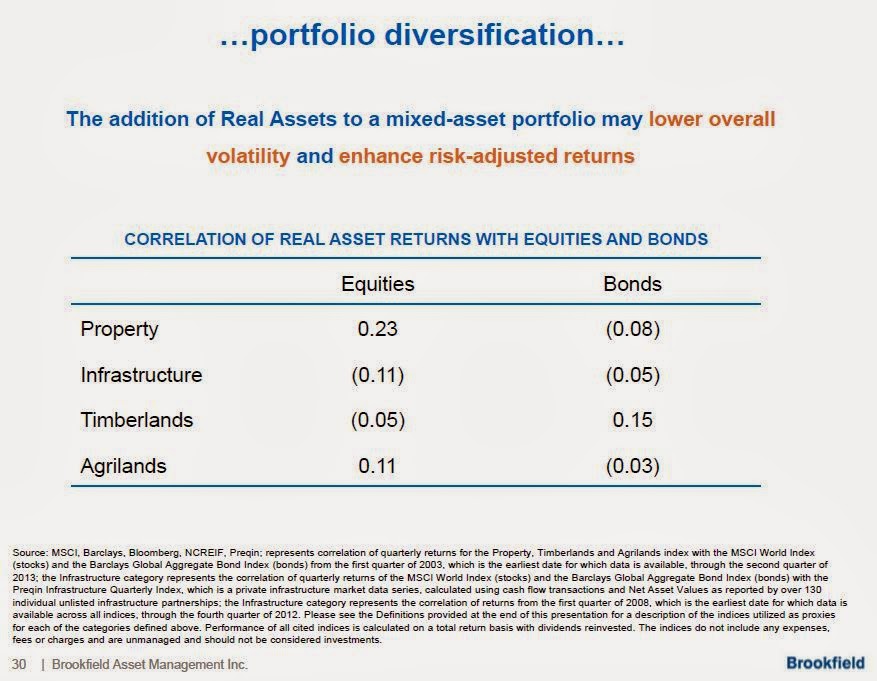

I’ve seen (and created myself too) the exact same sort of charts/tables but instead of agrilands/timberlands, the asset classes were (at various different times) managed futures accounts, hedge funds, Asian equities, Japanese equities, global equities, emerging market equities and commodity indices (and others). Some of these asset classes looked the best at various points on a five or ten year lookback basis, and almost always, things didn’t really work out too well going forward.

I remember strategists running around with presentations showing Asian equities in the late 80’s and early 90’s saying that you had to be there. Owning them would lower volatility of your portfolio and increase your returns. I’ve seen the same argument about Japanese equities in the late 80’s, emerging markets in the 90’s, commercial real estate, commodity indices in 2006/2007 etc…

I wasn’t in the business back then, but people used to show a similar table showing how adding managed futures accounts (CTA) would increase returns and lower volatility of institutional portfolios in the late 1970’s/early 1980’s. Slightly different, but option overwriting strategies were hot too at some point in the 1980’s; if you hire an options overlay manager to write call options on your equity portfolio, your return/risk would be enhanced. And if you can lower volatility and improve the risk/return, maybe you can lever up too!

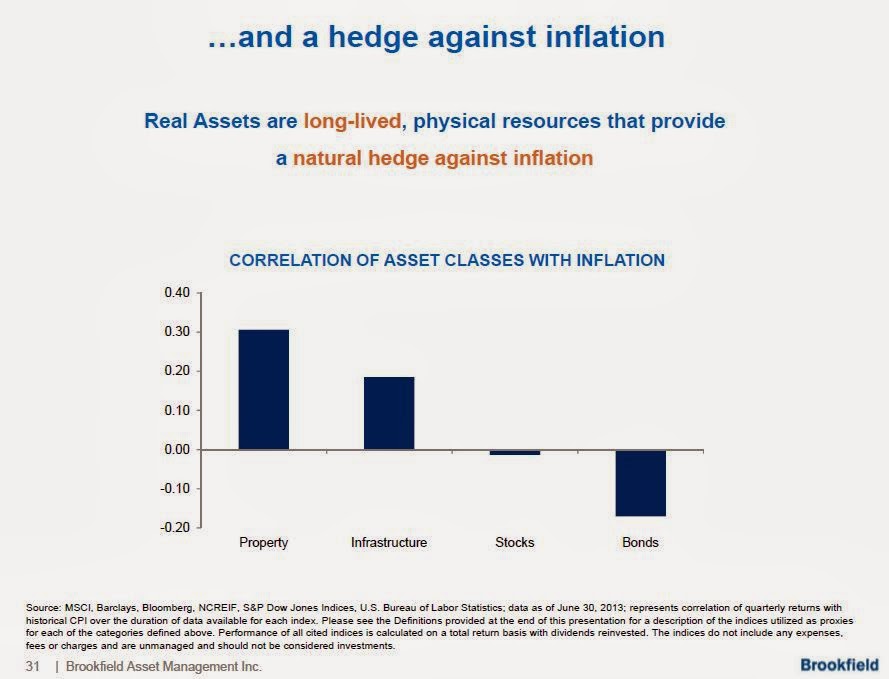

And now we have this added fear of perpetual, QE-infinity creating inflation down the line. So this slide adds to the excitement of the above slides:

So how can you lose? It’s a no-brainer, right? Good Sharpe ratio, low correlation to conventional asset classes and it even acts as an inflation hedge!

But again, I have the highest respect for Brookfield Asset Management. I’ve never written it up here as I never got the chance to or there was no ‘trigger’ to make me do so. Plus, I personally am not too big on infrastructure / real estate. But I have owned it in the past and may do so in the future. It’s really a high quality organization, so none of this is a reflection on Brookfield, but more of a commentary on what’s going on overall.

Conclusion

So are stocks the best place to be? I don’t know. I have no idea which asset class will perform the best over the next few years. I have no idea if this is the tippy top of the bull market (even though my recent posts might be indicative of at least a short term top!). I really don’t know.

And I don’t say all of this to say that we won’t enter a bear market soon or anything like that. We will certainly have another bear market, and I have no idea when. Buffett said that he would be very, very surprised if we had another 2008 soon. He thinks that won’t happen for a very long time because when people go through an experience like that, they tend to be cautious for a long time after.

But my comments are not so much defending the market so much as warning about trying to get too smart and trying to dance around avoiding what might or might not happen. Also, running to other asset classes just because it has a better 10-year rear-view mirror return with lower volatility and is uncorrelated to the stock market and bonds is not necessarily a great idea either.

This is not to say those other asset classes are bad. It’s just that people might run into them for the wrong reasons. And that would be the mistake.

ever looked at VRSN?

No, but i should. It's a BRK stock too. Lone Pine owns also. Recent news may be an opportunity… but don't know if it's an opportunity to rush in or out…

Did you have a look ? I was reading their Ks lately to get an idea. From what I understand they should have a pretty good position in negotiations going forward since they control a large and very significant part of the whole domain space (.com and .net, probably even larger if you exclude redirectors like .to). Say a new company tries to enter the market. They would have to offer lower prices to do so imo since VRSN's track record is pretty flawless (0% downtime over 15 years). Do you think that Amazon and eBay would choose to save a few bucks and instead run the risk that the transfer to the new provider doesn't work seamlessly or that their website cannot be reached for a short period of time ?

The business model reminds me of TDG. VRSN provides a small part of the overall business, the cost is small compared to the overall costs. However, the small part is crucial, if it stops working or some hiccups occur the potential damage is high.

Hi,

I only took a quick look and it looks interesting, but don't have a strong view at this point. It looks OK, though.

see low risk of that event, these are good lt levels, outstanding economics + great mgmt

To provide context for my question, I am in the Buffett camp in terms of seeing the US equity market within a range of fair value. Given that line of thinking and the fact that I am finding it more difficult to identify obviously discounted securities, I am inclined to look at more reasonably priced companies that are non-cyclical in nature, high quality (i.e. high returns on tangible capital), and are run by management teams that are disciplined capital allocators and will be willing/able to take advantage of future stock market declines by buying in shares.

As you have mentioned, financials are still cheap and you have high conviction on some very high quality banking businesses (JPM, WFC, etc.). My question is: Given the nature of the banking business and financial regulation, will these businesses be able to take advantage of relatively near term stock market price declines via share buybacks?

Yes, if share prices are attractive, banks can't wait to start returning capital to shareholders so that's a good thing for sure.

I probably wasn't clear enough with my question. What I am really referring to is the fact that it is possible for the banks to be constrained by regulators from doing large returns of capital via buybacks. Given the fact that the US banks are very well capitalized it seems like the Fed is going to further allow them to loosen the purse strings and return more capital. How confident are you that the banks won't find themselves constrained again by regulators when the next downturn occurs? If there can be no real certainty that the banks will be able to take advantage of lower share prices via buybacks during the next period of distress, then wouldn't it be more desirable to find companies that won't find themselves in that sort of position.

I personally haven't sold any of my bank investments and feel that they are still attractive, but this unfavorable dynamic in terms of the regulatory constraints on returning capital makes me inclined to focus my efforts on other things at this point. It also doesn't help increase my interest that banks, while still at attractive valuations, aren't at the sort of "no brainer" valuations that were seen a few years ago.

Oh, OK. Yeah, that question comes up on Dimon conference calls sometimes, and Dimon says that yeah, he can't know what the regulators will do so they will do what they can.

I understand your concern and I don't know either. I do tend to think regulation pendulum swings back and forth, and it might move back a little, especially when the 'authorities' want more economic growth.

And yes, I too think that it is not at all a no-brainer like it was in 2011, for example, when I started this blog… At the time I used to walk through the Occupy Wall Street encampment in downtown NY and I couldn't be more bullish bank stocks and all the pundits including 'star' bank analysts all hated banks and said they are cheap but there is no good reason to own them, lol… So much for 'experts'!

Thanks for your thoughts. To my mind, the fact that analysts were spewing nonsense during that period is really a function of the fact that they, presumably, can't take a long term view. If I had to tell clients what bank stocks were going to do in 3 months or something, I would probably end up spewing a bunch of nonsense as well. Klarman really nailed it in "Margin of Safety" with respect to clearly describing the edge that is conferred with taking a long term view.

Again, I appreciate your thoughts and the effort you put into the blog.

As a sidenote to the Brookfield presentation, I have seen a lot of people heading into infrastructure and similar stuff lately. Not because they have a ton of expertise but because it is a "real" asset, long-term and has a predictable stream of cashflows (think toll roads or something similar). Well, at least it is supposed to be this way. The problem is that those guys have zilch experience in these asset classes and therefore hire teams of specialists doing that stuff and telling them of course that everything will be perfectly fine in the end (that is why they were hired in the frist place, no ?). So they do the seemingly right thing but for the wrong reasons…

That's the problem, right? If they get in because recent historical returns look so good, they will be quick to exit when it doesn't look so good; they are performance chasers, basically…

Fully agreed. The issue with those assets is, however, that they are not exactly liquid… Not like GOOG or BRK or SPX. It is hard already to get in and even harder to get out. Think csah bonds back in 2008. All of a sudden liquidity was king and nobody wanted to touch bonds with a 10" pole. Similar situation here, but worse. On the other hand usually there is no mark-to-market so as long as you are ok from a credit risk point of view you just hang on (and never mind that those 50bps yield over the 30 years don't look so juicy all of a sudden).

From following Brookfield, they indicate that real/alternative assets would be part of the portfolio mix. There would be some performance chasing, but there is room to buy in to manage risk and inflation and so forth, no?

Of course, there are more players coming into the market as alternative/real managers, and I'm not sure if they have the track record or expertise of Brookfield.

Yes, those are valid asset classes but my point is that when things look really good in hindsight and everyone rushes in, things don't work out too well. For the really long term, things should be fine as long as they own good assets etc.

Really enjoy reading all your great posts. As a comment to the real assets, are people becoming acquainted with and comfortable with some lower rates of return? Especially with low interest rates having been here for a decade or so now, it seems people are more willing to lock into these 'real assets'. I think it is a sign of the times and a search for a place to put all that excess cash that seems to be piling up.

I don't know. This has been a specialists' playing field over the last ten years or so. Long term assets means you need significant experience to appreciate what can go wrong (again, over the long term). This is something you cannot replicate easily so I think some players entering this space now will figure out that their deals were not as good as they initially thought. Which doesn't mean that you can't make nice profits there, especially if you are on the right side of the table :-).

Really interesting post thanks.

For me it emphasizes the importance of 'bottom up' investing and not to get too worried about 'top down' events. Of course, you should always consider the macro environment when thinking of the future of an individual stock, if they will go bankrupt during a recession obviously you don't want to own them, but going short the market, or even hedging against the market is not something I think improves returns in the long run.

Personally, I think Brookfield is simply trying to tell people what they want to hear. Sure, they've got great assets and expertise, but hey it happens their assets have low correlation, good sharpe ratio. So why not pitch that. That's what you do when you're trying to raise money.

As for infrastructure/real estate, I actually find many opportunities (at least in the public market). Brookfield Infrastructure Partners, for example, is trading ~13x 2014 AFFO. That's very reasonable for a low risk growing income stream. And we're not giving any credit for future investments.

Canadian REITs are trading ~12-13x AFFO. Implied cap rates are reasonable for the most part. There appears a disconnect between REIT implied cap rates and the cap rates of underlying properties, which leads me to believe higher interest rates are already fully discounted. Canadian REITs already pulled back ~20% last year.. that looks like a bear market to me, albeit after many strong years. Insiders are backing up the truck at so many REITs.

I bought a couple industrial REITs that were yielding 7-8%, with payout ratio under 90%, benefitting from weak CAD/recovering manufacturing, all the while demand for industrial space continues to outpace supply. I don't know if they're good investments, but it's hard to picture what the downside is. The surprising part is the ease at which I can find these kinds of situations.

Though I guess the places I'm looking at is just a small corner of the "real asset" universe. So it might not be indicative of anything.

My 2 cents on the market: I still find good opportunities but it's becoming much harder to find "slam dunk" ideas like last year. I find myself either settling for great companies at reasonable valuation OR reaching for more risky situations (turnarounds, highly leveraged, cyclicals, company specific headwinds). Many of the "trapped value" situations are already unlocked by activists or otherwise. And on good growth situations, the market is really stretching out the time horizon.

An aside: I've always find Ken Fisher's views fascinating. I'm not even sure what's his style. He believes we're going from the skepticism stage to the optimism stage of bull market, i.e. we're in the middle innings. The economy is getting better (according to him, the only thing you need to look at is the Conference Board's leading economic index). For the most part valuations don't matter, but people freak out nevertheless. At this stage, just buy mega cap blue chips with high gross margins because the market wants consistency. And enjoy the rest of mid-late bull market.

You are hitting on a bit of a rift within the value community: If you are pricing the market, or if you are pricing a set of many individual securities, and you find it to not be attractive at all from a valuation standpoint, what do you do? (Set aside tax considerations for this.)

Greenwald generally recommends some index exposure, in a bit of a nod to required rates of return and perhaps even a bit of EMH.

Klarman generally goes to cash, and looks for event driven things.

Buffett generally does things other than buying securities in such an environment. Whether it was closing his fund as he felt 'out of step' with the market decades ago, buying privately held companies in a non-auction environment, selling options on indices and so forth. In this latest iteration, notably Todd and Ted have not had trouble finding attractively priced individual securities, and Buffett has found other innovative arrangements (e.g. Heinz situation).

That's a good question. I understand the rift. If things are not attractively priced, I don't think anyone should necessarily go out and buy things. You can sit and wait, of course. But do you want to go out and sell stuff you already own? Buffett didn't sell his two investments (he discusses in the lts).

So if you think about what you own as a business, like Buffett does with his long term holdings (what he used to call 'permanent' holdings, which we now know are not as he sold WPO, and he said the other day that he would sell his other stocks if he needed to to buy a business), then you shouldn't be selling even if it is overvalued.

I was curious about this too and last night reread the 1986 BRK letter and he said when stocks are overvalued he sells them, except for his 'permanent' holdings which he considers as businesses that he won't sell even if it substantially overvalued (or someting like that). Maybe I will do a followup post on that.

Also, as for hedge funds and mutual funds, there are practical issues that may require them to raise cash when they are concerned about the market; unlike BRK, hedge funds and mutual funds do face redemptions, and we have learned over the years that redemptions do occur at the worst times; people want cash back at the worst time to be selling stocks. So as a practical matter, some institutions may want to raise cash and keep them in certain times. That makes sense given what happened in the recent crisis.

Anyway, many value investors have different styles and will approach this stuff differently and I don't think there is any right or wrong way to go about it. It's just an important way of thinking that we should keep in mind and be careful not to fall into the trap of inadvertantly 'speculating' etc…

This is certainly an interesting discussion… Thanks for commenting.