OK, so this is another post that follows a discussion in the comments section (of previous posts). I think it’s pretty important so I thought I’d expand on a comment I made and turn it into a post.

Halo Effect

No, not the book. But the same idea. I think some of these top-down, market-timing mutual funds in the past have benefited from a sort of halo effect. For example, people read about how Soros made billions betting against the Bank of England. They read about how some hedge fund wizard made a killing shorting Japanese stocks. They read about a trader that had a massive position in index puts on the day of the crash. They read about how someone piled into subprime default swaps and made a killing during the crisis.

So they see all these people making tons of money while other, “normal” mom and pops lose their shirts in a nasty bear market.

And then they see these funds that promise to watch out for these macro factors and structure the portfolio accordingly, promising them that they won’t get crushed in the next bear market (never mind that there is a cost to that; a cost/risk that is not at first evident).

Most individual investors don’t have access to hedge funds, so these market-timing funds sort of fill that need to have an ‘alternative’ to the usual equity funds.

The more volatile the markets, the higher returns that the big hedge funds show, the better relative performance these market-timing funds put up in the short term, the more popular these funds get.

Market Timing Funds Have to Be Right All the Time

But there is a big difference between the big hedge funds and the market timing mutual funds. The market timing mutual funds, for the most part, have to be right just about all the time for them to do well. If they miss one bear market, their performance is in the tank. If they miss one rally, that can also destroy their performance. Once you do that, it gets exponentially harder to try to make it back.

For example, you can take some of the great traders from the past. Say, George Soros or Stanley Druckenmiller. I can’t prove this or know for sure, but I am pretty certain that if they had a mandate to hold an equity portfolio and then hedge it according to their market views over the past 30 years or so, they would not have gotten anywhere near keeping pace with the S&P 500 index. No way. Druckenmiller himself has said that he has predicted 15 of the last 3 bear markets (or something like that; I don’t remember the numbers but you get the point!).

Difference Between Market Timing Funds and Macro Hedge Funds

Contrary to popular belief, most of the high returns generated by macro hedge funds are not from timing the stock market. Yes, some have made tons of money shorting stocks on Black Monday (Soros was actually on the wrong side of that, famously having sold the low tick on Tuesday), shorting the Nikkei crash in 1990-1992 etc.

But most of the money, I would guess, in macro hedge funds were made in fixed income and currencies. Back in the 1980’s and 1990’s, there were a lot of strong and persistent trends, macro imbalances with sudden corrections and other things that allowed hedge funds to make tons of money. And these funds put these trades on with massive leverage; leverage that can’t be replicated in the usual equity mutual fund format.

So they can be wrong about the stock market for years and still make tons of money (also, if they are bearish and short, they don’t stay short for very long when the market goes against them).

However, market timing funds don’t have alternative sources of income. They live and die, basically, by being right about the U.S. stock market. And they have to be right year in and year out. It’s just impossible to do that. Not even Soros can do that.

A lot of macro hedge funds take massive bets, but they do so in many markets around the world. If they have no opinion about the U.S. stock market, they can still go long something else somewhere in the world. Like Buffett looks for the easy questions to answer, macro hedge fund traders do the same thing; they look for the easier questions to answer. They don’t have to know where the stock market will go.

One of the big macro funds today has a bunch of non-correlated trades on. So they can be wrong about the stock market or interest rates, or even both and still make money because they have different trades on with uncorrelated factors.

If you are a market timing fund, you have to be right about the stock market. If you are right, that’s great. If you are wrong, that’s it. It’s hard to make it back.

This is not to say, of course, that all macro hedge funds are good. It is very hard to make money in global macro hedge funds and there are plenty of failures there too.

I am only trying to illustrate the difference between market timing mutual funds and the global macro hedge funds. Some market timing mutual funds talk about going into various asset classes and flexibility to go anywhere, but it seems like they are still mostly driven by being right or wrong about U.S. stocks.

Analogy

OK, so here goes one of my analogies that might just confuse the issue. But anyway, it goes back to Rumsfeld’s known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. By the way, I am not a fan (or unfan) of Rumsfeld; it’s just a convenient expression.

Buffett is known as a great stock picker. He has done well for more than 50 years. But if you look at Wall Street analysts, they do no better than random. Why is this? The usual interpretation is that Wall Street analysts are just incompetent. But I beg to differ. Many Wall Street analysts are very smart. Yes, I’ve met some really, truly dumb ones. But most of them are normal, highly intelligent, hard working people.

So why are they so wrong all the time? Well, they’re not wrong all the time. They are just no better than random.

But again, just like asking Soros to hedge and unhedge a portfolio over the years, if you ask Buffett to look at a list of the S&P 500 stocks and pick the ones that will outperform over the next year or even five years and then pick the ones that will underperform, I bet he will do no better than random.

Why?

Because for most stocks, his opinion would be “I don’t know”. Most stocks would go into his “too hard pile”. If we force him to choose, buy, sell or hold, he will choose. But he will have no conviction. And he will probably do no better than random.

The key here is that in order for him to do well, he doesn’t have to have an opinion on most stocks! He only has to have conviction on the ones he understands well and has a strong opinion about. He can ignore the rest.

Wall Street can’t do that. Analysts, in aggregate, can’t say, “no opinion”. They have to say, buy, sell, or hold. Not to mention that they have to guess the next quarter’s EPS etc. I don’t know if Buffett would be any better at guessing EPS on a quarter to quarter basis than Wall Street analysts.

Again, it doesn’t matter because he doesn’t have to do that to do well! But Wall Street does. This is why Buffett is not often wrong while Wall Street is very often wrong. In fact, Buffett has been wrong about all sorts of things but it hasn’t hurt his performance because he knows what he doesn’t know (he predicted a housing recovery that never came, higher interest rates that hasn’t come yet etc.)

Back to Market Timing Mutual Funds

Similarly, market timing mutual funds, like Wall Street analysts, have to have an opinion all the time. They have to be long, flat or short. They can’t really say, “I don’t know” and just stay flat, as that is their only source of profits. Yes, some funds have flexibility to go elsewhere, but for all practical purposes, other assets will usually only be a small part of an equity mutual fund.

Macro hedge funds can afford to say I don’t know about the U.S. market and choose to do something elsewhere. They can put on massive, leveraged bets on things they have conviction about and don’t have to have a view on the U.S. stock market at all. They can just go out and find something they do have conviction about.

Fallacy of Overvalued Markets

When you look at these long term charts, it’s really easy to fall into the trap of saying, “gee, look how expensive the market was in 1929, 1962, 1972, 1987, 1997, 1999 etc… We should have shorted the market at these levels!”.

Yes, expensive markets are often followed by corrections. Sometimes corrections are meaningful, like in 1929, 1999 and 2008. Sometimes they are not, like 1987.

But this is sort of like the guns and bank robbers fallacy. All bank robbers have guns, but not all gun owners are bank robbers. Many large corrections and bear markets are preceded by overvalued markets, but not all overvalued markets are followed by bear markets or corrections.

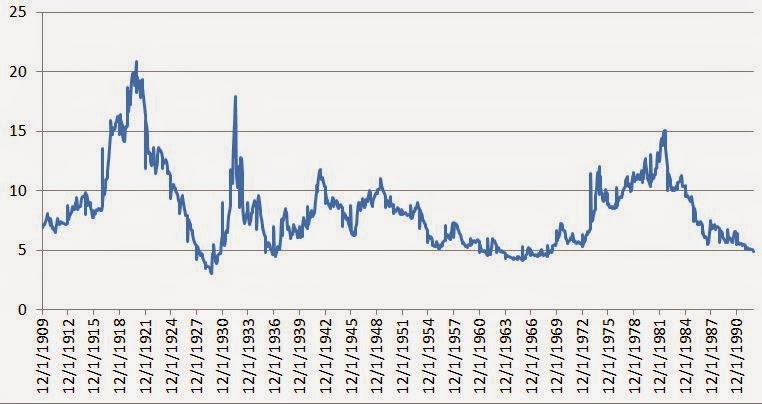

Here, check this out:

Again, Excel couldn’t handle the length of data so I chopped it off at 1909. If you go back further, the chart is even more convincing as CAPE10 (inverse) was under 5 in 1901.

If you saw this in December 1992 when the CAPE10 yield fell under 5% for the first time since the late 1960’s, it would have been perfectly reasonable to assume that the market is very overvalued, even more so than right before Black Monday. I didn’t do it, but you can put an average on here and then standard deviation bands around the 100-year average, and it would have told you that the market was really, really outlier expensive in late 1992. Look what happened to the market in that past after it got below 5% CAPE yield; 1929, 1937, mid 1960’s etc.

It is a visually compelling argument. It’s hard to argue that the market is not overvalued at this point. I just picked a 5% yield because it corresponds to a 20x P/E ratio that usually makes people think the market is expensive.

But check this out.

Where was the Dow and S&P 500 index back then?

December 1992 Now Chg per year

DJIA 3301 17613 5.3x +7.9%

S&P 500 436 2023 4,6x +7.2%

And this 7-8%/year return since then, when the market was just about as overvalued as ever is excluding dividends. That’s just the change in the index level. Throw in dividends and it’s probably close to 10%/year. From an expensive market!

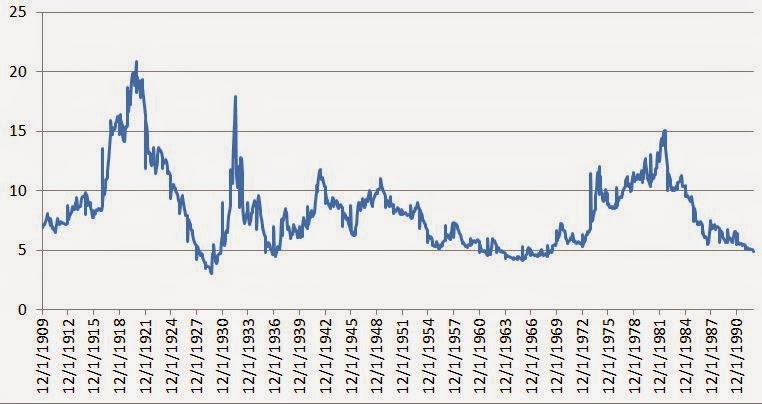

And then check this out:

If 5% earnings yield was silly expensive and you held to that ‘standard’ which has proven itself over 100+ years in the stock market, you would have basically been out of the market (or even short) for just about the whole period since 1992. You may have gotten in during the financial crisis, but then you would have gotten out again pretty soon after that.

It’s crazy, isn’t it? Now you see why a lot of people have been saying that the market is overvalued for more than 20 years!

This is why it’s so dangerous to make investment decisions based on this stuff. And again, this is why Buffett is such a great investor; he ignores it. Well, I’m sure he sees the graphs and charts and goes, whoa… But he doesn’t let this stuff distract him from doing what he knows what to do. And he isn’t tricked by these charts into thinking that he can guess where the market will go in the future.

As great as any argument sounds, you still really can’t know what is going to happen to the stock market going forward.

You can look at these charts and go, wow, returns are going to be lower going forward. I’ve seen those tables that show stock market return based on the P/E ratio of the market on the initiation date. Yes, higher P/E’s mean lower prospective returns.

But what I haven’t yet seen is a table that shows, for example, that when a P/E is 25x, that, say, there is a 30% probability of a 30% correction within the next three years such that if we get long at the bottom of such bear market, our total return from this timing strategy will be Y%. This could be a table. Maybe there is a 50% chance of a correction of 30% or more within the next five years after such a valuation, and if this happened, and we were able to go 100% long at the bottom of that bear market, our prospective return would Y% etc…

All of these possible scenarios have to be calculated, including the probability that there won’t be any correction greater than 20% within the next five years. And if the sum of all the expected returns in all those scenarios is higher than the prospective, buy-and-hold expected return, then you can say maybe it’s a good idea to try to time the market. But then again, we all know how these complicated calculations with layers and layers of assumptions go.

But anyone who has traded (and/or studied) equity derivatives knows, there is a cost to such opportunism and it can be calculated. For example, in the old days, there used to be interesting-sounding options like “down-and-in” options, or “lookback” options, and other trigger or barrier type options. These options were designed for buy-the-dippers. For example, you can create a call option that becomes effective when the market goes down 10%, and the strike price becomes the stock market level 10% lower than when you put on the trade. Of course, you would have to pay a call option premium to the seller for them to take that risk, and for them to effectively ‘trade’ for you. If the market didn’t go down 10% within the time period of the call option, it expires worthless and you lose your premium.

The theoretical value of these options can be calculated, incorporating the probability of the movements in the market, trading costs etc. And this theoretical cost would effectively be the opportunity cost of waiting for the market to come to your level. This has to be compared to the buy-and-hold, fully invested return. If, say, interest rates were 8% and the expected return in the stock market is (unlikely in this scenario) 1%, and the knock-in option is worth 3%, then maybe it’s a good idea to sit it out; you are getting paid 8% to wait, and out of that you pay 3% for an opportunity to get in lower, so you are earning 5% already; much better than the 1% you would get by investing fully now. Again, unlikely scenario, but I just did that to illustrate the thought process that would go into something like this.

Even simple hedges have their costs. You can buy put options to hedge against stock market risk, but those premiums can add up over time. And especially in this lower return environment, it’s going to be hard to make money with low return stocks when you dish out a bunch of money on put premiums.

But again, if you can precisely calculate the odds, maybe some sort of hedging structure makes sense.

But you never really hear anything like that. Usually, it’s something much simpler, like, “the market is overvalued because the P/E ratio is as high as it’s been in 100 years, therefore the market must go down soon so we will buy puts, short futures and buy gold”, or something like that.

Conclusion

So anyway, market timing mutual funds and macro hedge funds are very, very different animals. They are not even close in terms of what they do and how they make money. Even the best traders of all time, I don’t think, could time in and out of the markets if his sole mandate was to hold a U.S. equity portfolio and then hedge / unhedge according to his market views. No way. In fact, many of the great macro hedge fund traders have lost tons of money trying to short the U.S. market. But they make it up elsewhere in other massive, leveraged trades so it’s not an issue for them. Each trade is like a single poker hand; one bad hand or bad beat is not going to ruin their year; and macro hedge fund traders typically make many, many trades a year (as opposed to market timing funds that make very few decisions; if they are bearish due to market valuations, they will stay bearish etc.)

If a market timing mutual fund gets the timing wrong, it’s just going to be a total disaster.

Just as there is no way that even Warren Buffett can predict which stocks will go up and down in the future (out of, say, a list of the 2000 Russell stocks), even the best macro hedge fund traders couldn’t time in and out of the markets consistently.

And the key is that neither Buffett nor macro hedge funds have to do that. Just like Buffett has to only find the questions he knows he can answer (just buy the stocks that he thinks will go up and then ignore the rest), macro hedge funds can take massive bets when they see an opportunity and can throw the direction of the U.S. stock market in the “don’t know” bucket and leave it there for years if need be.

But just like analysts have to have an opinion on every single stock they cover (even if they personally may be indifferent and have no strong opinion either way most of the time), market timing funds have to always have an opinion on the market, and if they are wrong, they are dead.

It is impossible for market timers to get it right consistently all the time just as it is impossible for analysts to be right on every opinion they have on every single stock they cover.

But unfortunately, those people are in a game they can’t win. Buffett and macro hedge fund traders have the luxury to only pick their shots when they have conviction.

Having said that, not all macro hedge funds are good. Most are probably no good. And having said what I said about analysts, they do have a role to play in the financial markets. It’s not always critical for them to be right or wrong on stocks; they do act as a conduit between companies and investors. And they have sort of a high level ‘reporter’ role in keeping a professional eye on companies and report on various developments. Many analysts are valued not necessarily for being right or wrong, but for their deep knowledge about companies and industries that can be helpful to investors.

And no, I am not arguing that the markets will stay expensive forever. I am just trying to point out that it is not so easy as saying “the market is expensive, let’s get short!”.

very well done post

This comment has been removed by the author.

As always, great stuff! I do want to point out that the one could have bought long treasuries in 1992 and done pretty well on a relative basis. Also, if you measured returns at the end of 2008 or 2012, the analysis would look a lot different. Measuring anything at all-time highs tends to make the series look better than it would at different end-points. It would have also required a very, very strong stomach to simply hang on to the index through the 2000-2002 bear market and then the financial crisis. CAPE isn't meant to be a timing tool. It is a tool that lets one know what long-term, absolute valuations are at a given point in time. This will help to properly frame one's expectations. Jumping in and out of the market successfully is not possible. However, it is prudent to manage one's asset allocation and risk level based on valuation.

Thanks. Yeah, treasuries have done well. But in that world, people seem to have been even more wrong. I've heard calls for a bottom in yields since the early 1990's.

And yes, measuring things to a high is not necessarily good, but I just used what was convenient for illustrative purposes. Even if you measured to the 6500 low in 2009, that's still a 4.3%/year increase in price excluding dividends, or 6.3%/year including dividends (assuming 2% yield). So that's not bad; going from an all time high in valuation to a once-in-a-century financial crisis low.

And yes, CAPE isn't a timing tool, and my point would be that there really isn't *any* really good timing tool. And it is definitely important to look at this stuff to manage expectations.

And I agree, it's hard to sit through bear markets.

Buffett asked someone once why the market has returned 10%/year for 100 years and yet noone has a track record even close to that (of course, not 100 years, but any length of time). The market was there for all and anyone could have just bought an index (or portfolio of blue chips) and could have gotten really rich. And yet, nobody has done it (or not many).

Why? He said it's because people just can't sit still! They have to go in and out of the market because they read stuff in the newspaper and people talk about this, that or the other thing.

Mutual fund research has also shown that investor behavior is more detrimental to their financial health than the poor performance of the funds themselves! In other words, investors have realized returns in mutual funds that are far lower than the long term performance of the funds! Why? Cuz people need to get in and out and the wrong times!

Anyway, it is prudent to manage one's asset allocation and risk level based on valuation, but I have yet to see anyone do it well over time. Who has done it well and what kind of published returns do they have? I haven't seen anything, really…

Thanks for dropping by!

I appreciate the reply. My point isn't that a manager should monitor asset allocation for an investor. I am saying that the individual investor should monitor their own asset allocation. That being said, GMO has a pretty decent track record in asset allocation. Research Affiliates does a decent job. There are many value investment managers that are willing to let cash build as a residual of their process (FPA, First Eagle, Longleaf, IVA, etc.). I am in 100% agreement that market timing doesn't work and is generally not repeatable. However, asset allocation is not market timing. Managing risk is not market timing. Nobody should jump in and out and try to time markets, but rebalancing and reducing one's allocation to expensive assets is not the same thing as market timing.

Great post as always.

I agree. CAPE is not a timing tool. That being said, here is a good reply Tobias Carlisle wrote in his wonderful blog (Greenbackd)

"In December 1992 the Shiller PE was 20.45. The average return from 20.45 according to Asness’s chart was 3.9 percent per annum for the subsequent decade. The annual total return for the S& 500 TR was 8 percent per annum for the period to November 2001, which was about ten months from the eventual bottom of the dot com bust in September 2002. Including that final date reduced annual returns to 2.5 percent, which is slightly below the average return. It’s roughly correct over longer periods (10 years +).

3.9 percent is not a signal to sell out, it’s a signal to anticipate 3.9 percent from the market. It makes it possible to compare the returns available to other opportunities, which might be better. For example, the ten-year treasury in late 1992 was ~7 percent."

Regards from Spain

Thanks for that. That's precisely what the Shiller PE tells you; what the expected return might be. It doesn't follow that one should get out or hedge their portfolio. What we don't hear about, ever, are the people who got out in 1992, for example, or hedged their portfolio in 1992 and then unhedged at the right time to go on to outperform the market during the time period. That's where the fallacy is.

Thanks for filling in some details.

Yes, thanks for putting the exact numbers out there. The point of CAPE is to manage one's expectations and to measure opportunity costs. The opportunity cost of reducing one's allocation to equities at 20x CAPE isn't huge over the long-term. Now, that doesn't mean sell out of equities entirely. That means to manage the risk/reward in your portfolio and understand what to expect in the long-run going forward. That is how CAPE can help an investor.