The Magnificent Seven!

OK, I don’t care what you guys say or think, but that’s a cool picture. I may have even used it before for a similar post. If so, sorry. Anyway, it’s my blog so I can do what I want.

Anyway, this is just another one of those posts that popped into my head based on a question I was asking myself. It’s been on my mind for a while. I had more plans about this post, but I won’t do it all here and now. The question is, basically, what’s up with the Mag 7? How crazy is it? Is it Nifty-fifty all over again? Well, I sort of knew it’s not since I am aware of, and own some of these names. But I wanted to sit down and really look at what’s going on. Look at this table below.

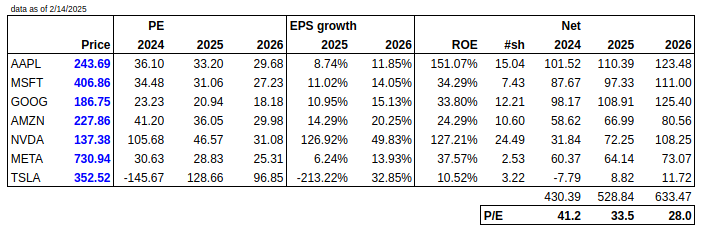

This is the Mag 7. I pulled out the EPS figures for 2024, 2025 and 2026 and calculated the P/E ratios of each of them, so it is sort of a “sanity check” on them. Not all the data is here, as the table was too wide, so I hid that columns that were just used for calculating. But you can trust these numbers are pretty good, as good as you can get from plucking them off the internet.

The first thing you notice is that other than NVDA, P/E ratios aren’t all that crazy. Not cheap. But not all that expensive either. As I said, in a world where the market spends more time above 20x than below, this is not all that outrageous. By the way, this is related to my other post, but when I first started in this business in the late 80s / early 90s, the mantra, the model we burned hard into our heads was that the market has traded at an average P/E ratio of around 14x for close to 100 years, and that in recessions / bear markets, the market goes down to 7x P/E, and that’s when to buy. And when the P/E gets up over 20x, watch out! Any chart you looked at back then proved it. The 2 times that was most obvious was 1929 and 1987. Therefore, it stuck. A P/E > 20x == Crash!! But I have long realized that is not relevant at all (as my many posts show). And it seems like many investors haven’t really changed that model.

Anyway, the other thing to notice on this table is the lower right hand side. I sort of grabbed the shares outstanding of all the companies, multiplied it by their EPS to get a net earnings figure to calculate a sum of earnings of all the Mag 7. And then I used the market cap total of all of them to give you a sort of combined P/E ratio. And based on that, the Mag 7 is trading at 41x 2024 earnings, which is close to ttm earnings. and 33.5x 2025 expected earnings, and 28x 2026 expected earnings. I know, expected earnings is sort of rubbish. Nobody gets that right. But we gotta start somewhere, right?

By the way, if you exclude NVDA and TSLA, the above would be 32.6x, 29.6x and 25.8x P/Es, respectively. In this case, this is valid to do, because you can actually create a portfolio of high ROE, decent growth stocks at that valuation.

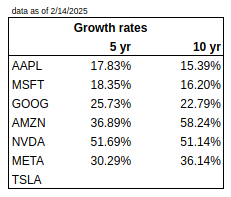

And then look at the ROE of each of these companies. And then look at the historic growth rates, 5 and 10 year of these companies (table below). And then look at the future growth rates (well, yoy of 2025 and 2026 earnings… Long term earnings growth estimates are even sillier than ntm earnings estimates so I won’t post them here). For reference, the historical earnings growth of the S&P 500 companies for five, ten and twenty years were +7.5%, +7.0% and +6.3% respectively.

Here are the historic growth rates of the Mag 7:

And now think of it this way. Let’s say the Mag 7 was a modern-day, techful version of a conglomerate like BRK. Its subsidiaries have grown tremendously in the past 5 and 10 years. Earnings will collectively grow 23% in 2025 and 19% in 2026 (willful suspension of disbelief may be key here), and look at the high ROE of each division (OK, I was too lazy to calculate a weighted average).

And this conglomerate is trading for 34x earnings! Or less than 30x if you don’t want NVDA and TSLA. Think about that for a second. How many ideas with those metrics can you find? Let us know in the comments!

Of course, this was just an exercise for me in thinking about this. This is not to say I think you should go all in and buy the Mag 7. I only did this to see how bad this Mag 7 dominance is, and put some color on it to see how terrifying this really is.

What I planned to do, but decided not to, was to illustrate an idea I talked about in the past. I was going to take this virtual conglomerate and break down sales by actual sector. So instead of calling these tech firms, call them for what they are. But I really couldn’t decide. It’s easy to call AMZN a retailer, for example. YouTube is a big part of Google, and the rest of Google is advertising. So is Facebook. They compete with linear television, radio and other forms of entertainment in the past, and they make money from advertising, just like old media (including magazines too…). So we can call it media and advertising, not even “new” media. Just media. Tesla is an automaker. AAPL is more like the old Sony; consumer electronics. Basically every single consumer electronic product ever invented rolled into one product. They do media too; music, streaming etc. Gaming too. Only NVDA and MSFT sort of feel like the conventional ‘tech’.

My point was going to be, the Mag 7 domination may or may not be a problem, but it is quite diversified as a virtual conglomerate.

The Markel Situation

OK, so someone mentioned Markel in the comments of my previous post, or maybe in the Twitter comments. Yes, this is a very interesting situation. My first reaction is kind of surprise, as I always thought of MKL as a pretty well-managed company with a good idea, vision, goal etc. So for someone to come in and try to get them to move away from their model is a little bit of a bummer. Sure, there can be improvements, so maybe this is not all bad. But who knows. Sometimes, activists come in with the goal of acquiring a bunch of stock, forcing some actions to get the stock price up, and then leave. The “actions” may or may not be in the best interests of the long term holders, even though many may be happy with the short term lift. For example, if they are forced into a sale, that would sort of suck, right? As it would give all of us one less stock to invest in that we like. I don’t think I want to be an owner, of ,say, Tokio Marine, if they bought MKL. The ideal scenario, if a sale is forced, is of course, BRK. BRK may let them stay independent and run the way they are now, and there may even be some investment synergies with BRK; more investment brain power helping each other. On the other hand, we all know investing by committee doesn’t work, so we wouldn’t want some investment committee to form at BRK.

Anyway, I haven’t really looked very closely at this, and haven’t heard much more detail about the proposals, so don’t have a whole lot to say yet. This may merit a full post at some point later when we learn more.

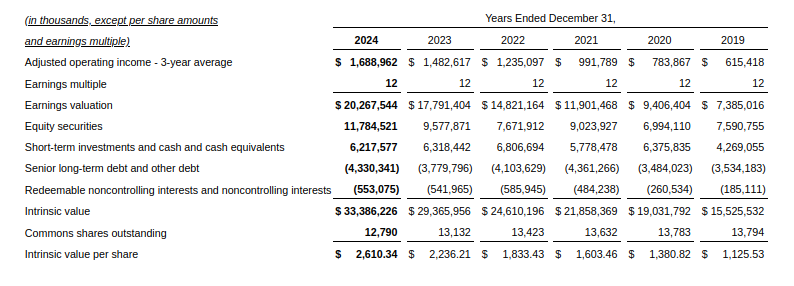

First of all, let’s look at their investment returns. I think this table was published in this form starting in 2023. This is a great table to keep track of how their investments are doing. This is from the 4Q 2024 earnings release.

By the way, the five-, ten- and twenty-year total returns for the S&P 500 index were +15.4%, +13.3% and +10.5% respectively. So MKL’s equity portfolio has been underperforming in all of these time periods. I guess this is not unusual in the value investing world, so maybe we should not be surprised.

By the way, since we are looking at equity returns, let’s just do a quick comparison of the stock price of MKL too. While we’re at it, I just tossed in BRK too, and compared it to the total return of the S&P 500 index for the above same, five-, ten- and twenty-year periods.

This is sort of a surprise. Well, we know that BRK is so big, it is having a hard time beating the S&P 500 index. It barely beat it for the 20-year time period, which is amazing. In case you haven’t looked recently, BRK’s market cap has exceeded $1 trillion. Book value is a whopping $630 billion. MKL’s market cap is $24 billion with book value of around $17 billion. Why I say it’s surprising is because way back when we were all looking for BRK-alikes, one of the arguments for investing in MKL was that it was much smaller, therefore much nimbler, with many more potential stock investments (larger pool of potential ideas) that can move the needle than BRK. You are talking about $630 billion in net worth versus $17 billion. This has obviously not panned out as MKL has not only underperformed the S&P 500 for all the time periods, but it has underperformed BRK too, which has a big handicap (size).

Anyway, back to the earnings release. The cool new thing is that they have clarified and published their concept of intrinsic value. There is a whole section at the bottom of the 2024 4Q earnings release, so if you haven’t already, you should go take a look and read it carefully. It is interesting.

I think this sort of thing has been mentioned in the past, so maybe there is nothing new here, but MKL does look at a model similar to the equity plus float model that was so intensely debated years ago about the BRK valuation. I also jumped into that argument, but my point was merely that BRK’s float was in fixed income / cash, and that with the really low interest rates, the float should not be valued the same as the rest of the ‘equity’.

You can make the same argument here, but rather than get into the discussion again, I will just talk about sort of a compromise way to look at it. For now, I will say that the above valuation is fine, and I will explain why. There was also an argument that float can’t be calculated as equity if you look at liquidation value, as that will obviously go away in a liquidation (it is a liability). But then, you can argue the same for any business. If you liquidated CMG, the pots and pans won’t be worth as much as CMG as an ongoing business.

As I said the first time around when the discussion about whether BRK’s float should be valued as equity, I argued that the float can only earn fixed income-like returns, not equity-like returns, so it should be discounted to reflect that.

Similarly, here, instead of arguing about whether MKL can just add equity securities, and cash/short-term investments to their valuation, we can frame it another way. Since they decided that MKL can be valued at 12x operating income, much of the work is already done. Thanks for that.

Now, we can just model the potential returns of the ‘investments’ and then capitalize it at 12x operating earnings. Right? Why not? So let’s say that they have and will maintain $12 billion in equity securities over time, and short-term investments, cash and cash investments stay around $6 billion. That’s $18 billion in investments. Fixed income investments are not added back, which means that income from the fixed income portfolio is already included in the adjusted operating income. So that’s fine. We don’t care either way for now.

Let’s just look at the $12 billion equity portfolio and $6 billion of cash and short-term investments. The reason why we don’t like to include unrealized gains and losses in earnings is because it is lumpy. So let’s just ‘normalize’ it and assume equities return 10% over time. And short term cash and cash equivalents is easy (well, not really, as we don’t know if it’s going to 7% or down to 3%). Let’s just say short term rates will stabilize at around 4%. Then the portfolio will return 8%, or $1.44 billion. Capitalize that at 12x, and the portfolio is worth $17.3 billion. To make it worth exactly $18 billion, return on cash/short term needs to be around 5%. But, OK, why split hairs? Equity returns of 10.5% and cash returns of 4% would also get you to $18 billion. So you see what I did. Instead of just adding on the value of the portfolio (which is fine for them), I just normalized an assumed long-term return on these assets and then capitalized it. Of course, this level / weighting will change over time, so it can only be a snapshot estimate of how much the portfolio contributes to MKL’s earnings.

And the good thing is, you can get granular and make your own assumptions about these future returns and get a more conservative estimate. If equity returns over time go down to 8% (with the same 4% short rates), then the $18 billion portfolio would only be worth $14.4 billion at a 12x cap rate. It makes sense, right? It’s not right or wrong or anything. It’s just another way to look at it. You can plug this into a spreadsheet and change around the assumed return figures and you can come up with your own intrinsic value.

Markel Ventures

Oh, and one other thought is about Markel Ventures. I thought it was really cool and a great idea. As even Buffett says, when you are fishing in a pool that includes unlisted businesses, of course your opportunity expands. When the stock market is really expensive, sometimes private businesses are not. BRK has benefited a lot from this, even though some are arguing that the many of these wholly owned businesses may not be doing as well as we think. But, OK, that’s a different topic. Let’s just say that the idea itself is a great one, and it can even serve to stabilize MKL over time, with unlisted businesses that Mr. Market can’t crush (both stocks and bonds are vulnerable to that). I like it.

However, here is an issue that even came up when talking about BRK many years ago. A while back, Buffett used to post these long term growth figures; how much the privately owned businesses grew in terms of pretax profits, and how much float has grown over time etc. One thing that bothered some people was that it was hard to know how well the private businesses were actually doing. Even if it grew a lot over time, it was hard to tell if the growth was ‘organic’, or if some acquisitions were funded by fresh capital. If so, who cares about the growth? But I don’t think it was Buffett’s intent to say that the businesses were growing on it’s own.

Now, to MKL, when you see the growth in Markel Ventures, how do we know some of that growth didn’t come from them selling some listed stocks to buy another private business? If so, that figure, the growth, is kind of irrelevant. You can argue, when CMG opens a new restaurant, they are investing to build a new restaurant. Yes, but that comes out of CMG’s balance sheet, so it is their own, internal growth. But for MKL, what is the ‘organic’ growth rate within Markel ventures adjusted for capital going in and out? The equity portfolio returns are certainly adjusted for that.

But possibly more important than that growth figure, what about the return on capital? BRK used to show the income statement and balance sheet of the MSR (Manufacturing, Services and Retail) segment, so you were able to see what they collectively earned in ROE. Should MKL not publish something similar for Markel Ventures? I guess the key question for investors, is, how is investing in Ventures doing versus the S&P 500 index, or some other benchmark? Venture capital and private equity funds report returns based on estimates of fair value, but those returns are, of course, adjusted for whatever capital is invested. They can’t just improve returns by injecting more cash into a fund.

What is the return on investment on those investments? If not much change in value, what about the cash returns on investment? I think some sort of metric would be useful to investors. I think it may be helpful to show that these investments are doing well compared to other investments.

Sure, many other companies show growth of the various operating segments without showing how capital is moved around between them. But the problem here is that people look at it and want to compare it to investments.

Conclusion

It seems like this sort of activist action is inevitable given the long term underperformance of MKL as seen above. I have been and am still a huge fan of MKL, and am a believer in the model. But at the same time, it gets difficult to defend when the numbers don’t support it. It’s OK to have good times and bad times, but 20 years is a long time to underperform, both in the equity portfolio and the stock itself. I will still support MKL, as I would rather let the model play out rather than to take actions to optimize short term performance, which may ruin the model for the long term (with this sort of threat, will private businesses want to sell themselves to MKL, not knowing when an activist will come along, force a sale of some businesses to new owners who may possibly pull a DOGE? BRK is a trusted buyer and long term owner of businesses. Will MKL be able to develop that sort of reputation?)

The size of BRK, the high ownership of BRK by Buffett himself, and long term owners have long protected BRK from this sort of thing. But insiders don’t own a significant amount of MKL, and the nature of the shareholders is not as apparent as hardcore BRK owners. I’m sure there are a lot of hardcore believers and long term owners, but who really knows? If this gets into a proxy fight, how will it go? Will BRK step in as a white knight? BRK need not acquire the whole company, but would MKL issue a bunch of new shares at an attractive price to BRK?

I have no idea, but it will be interesting to see how this plays out.

Anyway, maybe I will come back to this subject when I learn more about it and dig in a little more.

I fear that, similar to some of the other poster children of the “value” community, we ( I am an MKL shareholder) have been investing for the long, well-written reports and membership in the shrewd investor club, not for the underlying execution. Certainly, since around 2005. I remember during 2020, when bargains became plentiful, Markel was selling public equities and not repurchasing shares. Something about high return opportunities in insurance. Management promised to let us know how that worked out. Spending money on outside consultants to confirm obvious capital allocation missteps and underinvestment in your technology stack feels like a symptom of the problem and not the cure. Sadly, a sale of the business at a competitive price might be best for long-term shareholder value. Patients has a price.

*patience.

You forgot to mention the issuance of preferred stock during Covid as well. Tom said it was all borne out of conservatism and I guess if you consider the range of possible outcomes they needed to guarantee the business survived. But I don’t disagree with what you are saying.

This is a great point

The question for me was always whether Markel has the opportunity to outperform Berkshire because outperformance is a requirement given the higher intrinsic risk of Markel vs Berkshire. For over a decade I stuck with MKL until I could no longer deny that BRK was simply a better run collection of businesses and that prospective returns were likely to be better at BRK. I like management very much and am not saying they can’t yet succeed but for my capital it became too hard to justify not just owning more BRK instead.

Yeah, I own it sort of as supporting the culture and what they are doing etc. But it’s never really gotten traction. I own BRK too, but honestly, I don’t expect all that much better than the index, but I also own it for the same reason; love the culture, what it represents. But not expecting it to do all that well. Probably will do OK, which is fine. Neither of these positions for me has been as big as some BRK owners, who have 30%-50% or more of their net worth in BRK… So they are like baseball cards in my collection. May not be huge winners, but it’s OK because I like them.

Yes and not many truly appreciate how much higher that intrinsic risk is either, it is dramatically higher.

Fairfax makes up 43% of my portfolio, with Markel and Berkshire in 2nd and 3rd positions, both roughly equal at 8%.

My impression is that many investors misjudge the risk/reward. The reason is simply the coloured past: we are just coming out of a decade where float was historically worth little (with interest rates close to 0%), where growth value historically outperformed (not great for FFH, MKL, BRK as value investors) and we had a soft market.

Why am I talking about ‘coloured’? Because we are always subject to the bias of overvaluing the recent past and extrapolating it. But 10 years is rarely ‘average’. In the 70s we had high inflation and the oil crash, high interest rates. I wouldn’t say we had a similar economic scenario for businesses in the 2010s, for example.

And yet we forget that all too often. The best example is Brooklyn itself: in 2011 (or was it 2014? from memory) Brooklyn already compared Berkshire and Markel. At that time, Markel was ahead of Berkshire in all the periods analysed. Reading the article, one could therefore be more hopeful that Markel would continue to outperform Berkshire.

Why do I see a bias? Berkshire and Markel differ not only in terms of their sheer size. They also differ in terms of float per share. Markel has a multiple on this metric compared to Berkshire (I don’t have the factor on hand right now). Markel’s outperformance in 2011/2014 in the rear-view mirror was not least due to the fact that there was much higher interest on the float during the period under review than afterwards. Of course, an earlier onset of a hard market would also have given Markel with its larger insurance business a bigger boost compared to Berkshire.

As important as it is to keep looking at and scrutinising management (and Markel currently looks worse than FFH and BRK in the rear-view mirror), it is also important not to compare apples with oranges. FFH and Markel may still be apples as insurance companies, but BRK is more of a value conglomerate with insurance as one business among many others; and to stay with the image, more of a pear.

In my opinion, another overarching question is whether larger companies are really less risky per se than smaller ones.

I would say, for example, that FFH reduces its risk with its international positioning. They have self-sufficient insurance businesses spread across the globe, so to speak. In addition, large parts of the business portfolio are in India and Greece. This makes FFH much more diversified worldwide. I don’t want to go against Buffett, who sees ‘America’s best days ahead’. But Buffett also has some of his investments in Japan and many of his businesses generate sales worldwide (not least Coca Cola, American Express and Apple)

Another point concerns the ‘margin of safety’. As a value investor, I would say that an equity portfolio with a large margin of safety (and the favourable purchase of companies or unlisted company shares) reduces the risk. In my opinion, FFH is clearly ahead in this area. A few years ago, FFH sold its pet insurance business for well over $1bn; it had bought it for $30m about a decade earlier. Eurobank, Poseidon, Digit, KI, Bombai Airport (and many other investments in India, Greece and the world) are largely (extremely) strong performers, but are still largely very favourably valued on the stock markets and in the books (Eurobank with a P/E ratio of 6).

Another advantage of MKL and FFH is certainly their smaller size: both have managed to develop stable sources of income that fluctuate little. Certainly even more so than BRK, but still quite secure thanks to the diversification of income streams, own companies, etc. The longer investment horizon (even smaller investments can move the NAdel), the ability to build up and reduce positions more quickly, to expand into other countries, sectors etc. increase flexibility. And flexibility is a factor for security compared to immobility.

Berkshire certainly has other factors that reduce risk (more so than MKL and FFH). But I am not convinced that Berkshire (especially as Buffett will certainly – unfortunately – not be at the helm of BRK for very long) has the best risk/reward profile. The potential rewards are definitely lower at BRK than at the other two – and even the risk attribution is not as clear-cut as it is often made out to be.

Everyone has to make their own analysis, but I see FFH as having the best Risk Reward, followed by Markel and BRK.

Do you manage $?

Agree. The quality of the BRK businesses have always been better on balance than the MKL ventures businesses. The returns on capital have never been great. I don’t think there is any special edge that MKL has in buying private companies. I personally think the secret sauce of Markel was not in being able to be a mini-BRK, it was not even that they had a good stock picker (Tom is good, not great; and perhaps only average). Their biggest advantage is the simple decision they made a long time ago to put their float into stocks instead of bonds. They could have done just as well just buying the SPY and spending all the time they spend on stock picking just focusing more on insurance. It hasn’t hurt them to pick stocks, but I think the biggest advantage the company always had was that they are a great insurance organization and they optimized the asset allocation toward stocks instead of bonds. Just sticking with that simple formula and using any excess capital to buy back shares would have created a lot more value.

I’d easily recommend buying their own stock back or just buying more SPY rather than buying these privately owned businesses.

“The question is, basically, what’s up with the Mag 7? How crazy is it? Is it Nifty-fifty all over again? Well, I sort of knew it’s not since I am aware of, and own some of these names.”

Care to share which names you own and why?

I own MSFT, GOOG, AMZN and NVDA. NVDA, I lightened up a lot over the past year as I was afraid it was getting too crowded a trade. I have owned the others for a long time. AMZN, mostly because of AWS, MSFT only after Nadella took over and programmers told me Azure is very interesting etc., and GOOG is probably one I’ve owned the longest, just because of its dominance, and I thought they had the smartest employees anywhere. This can be said of MSFT and AMZN too. Basically, when you start investing based on management, you have too look at these companies. Also, understanding the dynamics of winner take all (thanks to the book, Singularity is Near by Ray Kurzweil), and how technology is changing everything, NVDA fit into that as they provided a solution to the flattening out of Moore’s law; I bought NVDA even before the bitcoin bubble took the price up… that made me nervous and was going to sell, but then AI hit and…). Of course, big tech is sucking everything up. Rather than complain about it, I just chose to get on the right side of it, lol…

These are crowded, very popular investments at the moment, of course, so I am looking for any excuse to lighten up on them…

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on your Mag 7’s. I wouldn’t dismiss continuing to hold them just because they are “crowded” and/or “popular”. Do agree though that most are priced for future perfection.

I’m a holder of GOOGL as I believe they are still reasonably priced with dominance in so many areas (search, video, cloud, self driving and possibly soon to be AI). Antitrust could be a risk for GOOGL, or possibly not as a break up could result in the separate parts being ultimately worth more than the sum of the parts combined.

Guess we’ll see.

Are you not concerned about big capex spending by the Mag7? P/E might become not such a meaningful metric to value those businesses considering they are becoming very capital intensive (or at least more capital intensive than they used to be)… thank you !

That’s a really good question, and one of the things that popped up in my mind when I saw this big rush, especially figures like $100 bn. It is an astounding amount, if it’s true GOOG and MSFT are going to spend that in one year. Usually, they are in the $20-30 bn range, I think. AMZN is already capital intensive (dist centers, trucks, etc…).

But GOOG/MSFT have plenty of cash / liquidity and cash flow to easily pay for this. Plus, I think this sort of capex is more ‘flexible’, than say, INTC in the old days building huge factories or other, traditional capital intensive businesses. Maybe I’ve drunk too much tech Kool-aid, though.

Anyway, liquidity is not an issue, and impact on ROE may not be much if MSFT/GOOG has all this liquidity already on the balance sheet (which is a headwind to ROE). The other thing, of course, is if they invest $100 bn in servers for AI, and it is depreciated at the usual 5-6 years, that’s $17-20 billion in depreciation hit to earnings if the AI investment doesn’t lead to incremental profits. It will be interesting to see what the return actually will be on this $100 billion. But even if they don’t earn much, they already earn close to $100 billion so it won’t be a huge hit to earnings if they produce no revenues at all… Well, of course, 15-20% is certainly big, but not business destroying. Plus, these investments will probably go a long way in enhancing the products throughout the system, so it will be hard to judge pure incremental or marginal return on this investment.

Also, keep in mind, just because they say $100 bn doesn’t mean the whole $100 bn has to be spent this year. I assume they are smart enough to move forward, but adjust as they see what’s happening etc… This is not like a signed contract, say, to build a $100 bn mega-factory somewhere, where it becomes an all-or-none deal…

Oh, oops, my comment is from browsing stuff through 2023, capex has already grown dramatically in 2024 too… I haven’t been through 2024 full year for a lot of companies at this point…

ChatGPT estimates GOOG’s value at $3.2 Trillion using sum of the parts:

https://chatgpt.com/share/67b380a1-80c8-8010-a8a3-d535b0605283

In context, $75 billion in Capex is not that big of a number.

Google’s 10 yr, 5yr and 1 year returns on invested capital have been 29, 31 and 33% respectively.

Spending $75 Billion in Capex seems prudent as long as they can continue to generate those kinds of ROIC numbers .

Small nitpick: I think your NVDA numbers are incorrect – their fiscal year ends in January, so FY26 is essentially CY25. I see $4.45 for CY25 and $5.46 for CY26 for consensus, which puts it at 31x and 25x, respectively.

Ah, thanks for that! I knew there would be some CY / FY issues. MSFT too is June-end, I think. So NVDA looks much better, then.

Dear Brooklyn Investor – I always enjoy your posts.

However, with the long term track record of MKL, it is clear that they do not walk the talk and Gayner is a merely an average CEO. Their valuation has been supported by a cult like dedication to “value investing” and the “BRK model”. Gayner’s investments look like closet indexing to me. In that case, what is the point of being active/in housing investments when you could just buy the index? That would rip out a lot of HQ costs and maybe free up management to focus on fixing the (re)insurance and ILS businesses. Secondly, they walked away from Allied World in 2017, letting FFH scoop it up (AW is now hitting it out of the park) and instead diversified into ILS business outside their core specialties. As a result, they are neither here nor there. They then decide to launch MKL ventures. The long term story here makes sense – an uncorrelated source of earnings and I support that.

In contrast, flying under the radar, and significantly outperforming MKL is FFH – I think you would enjoy taking a look at that and making some comparisons.

I agree. FFH made some mistakes, came clean and done well both on the investment and underwriting front since then.

I do own FFH too, and am surprised at how well it’s done in the past 3 years. Maybe all of this stuff merits another post. Stay tuned…

There are many Buffett wannabes. There are very few who are successful.

I think the constant comparison of MKL to BRK is a bit of a smokescreen put out by MKL longs…it is an OK company and the insurance model that they use with the ventures and equity is interesting but I think there are better places to invest.

Hi Brooklyn, always get a lot from your posts, thank you. I found the previous post about S&P 500 valuation against ten year treasuries informative and clear. I therefore wonder why you didn’t make life easy and use the same method for valuing the Mag7? To my mind looking at yields is much more straight forward than PE ratios. Any chance you could value the Mag7 again, this time against 10 year treasuries? Thanks.

Yeah, the thing is, for the S&P 500 index and 10-year, we have data going back a long, long time, so can do all sorts of analysis on it, whereas the Mag 7 is not all that old, so the same sort of analysis wouldn’t really work. Best you can do is get a fair value of the S&P, and then see where they stand in terms of premium / discount to the index etc…

Thanks for answering my question

Oh wow, a new post – thank you! 🙂

That’s two really, really interesting topics. I own Meta and owned a lot of AAPL (through BRK) and som thoughts seem familiar, but I haven’t dinged that deep into the Mag 7.

Regarding MKL just some remarks:

– intrinsic Value of FLOAT: You are right, that Float can’t be invested into stocks and equity and from this perspective (alone) I’d agree, that float should be worth less than equity. But if the insurance business itself makes profits, you’d have to add that profits. Let’s say, the premiums could be invested with 4% and the business has a Combined ratio of 94 – then you’d have an another 6% earned on the premiums/float. So 4% plus 6% gives you 10% – and equity like returns. Of course, having a CR of 94 isn’t an easy thing to do. But we haven’t added growth of float (which shouldn’t be below inflation over the longterm, if an insurer wants to stay profitable. So maybe a roe of 10 on float is not totally off the mark. I have to admit, that I haven’t a clear perspective how to value the growth into a formula (Is it like 4% yield + 2% CR + e. g. 4% growth of float = 10%)

– FLOAT, another perspective: As float isn’t equity it doesn’t contribute to the “E” in “ROE”. But at the same time, the returns of float add to the “R”. from this perspective, float to me seems like a hidden magic power. If an insurer manages to e. g. grow the equity part of its business equitylike (say 10%) and than you can add e. g. 5% earnings on top just from the insurance business (bond-like yields on float + CR below 100 + growth of float), than you have a business with an roe of 15%, even though you have grown your equity just at the same pace as all other businesses.

– Comparison of BRK and MKL (and FFH). I own all 3 since around 2011 (BRK for longer). It always strikes me

In the beginning, Markel was the best performer, Berkshire was average and Fairfax made several decisions that really weighed on performance. And then it changed: for the last 5 years Fairfax (underlying it started getting better in 2016) has been doing everything right and Markel has missed a lot of opportunities, a quality problem in the insurance business became apparent, etc.

It’s also interesting to see how strategically different the three have acted over that 1 and a half decades. First Fairfax bet on deflation (‘Black Swan event’), and now they are leveraging their own stock. They also went extremely short before interest rates exploded (while Markel continued to ride his boot). Fairfax insurance business became more profitable (very!) since 2011, while Markel got worse. Fairfax massively expanded its insurance business during the insurance crisis (Berkshire a little, but that didn’t really move the needle). Berkshire bet heavily on Apple while Prem railed against the high valuations in tech. Now Berkshire is going into cash while Fairfax is buying back shares, betting on India (and Greece) and is heavily invested in equities and corporates. Markel expanded ventures. Back then – 2011 – Tom Gayner’s returns looked very good in the rear-view mirror over many years and decades; now Berkshire and since a few years Fairfax is clearly ahead. Fairfax has also established a global insurance business in the last decade (REALLY global), Markel focussed on ILS. For many years Markel looked like the winner, well ahead of Berkshire and especially ahead of Fairfax. Since the start of the hard market and the turnaround in interest rates, that has totally changed: Fairfax seems to be doing everything right that they had previously done wrong, Berkshire is doing quite well too – and Markel is now the ugly duckling.

When I look at it like this, I find it enormous how different the strategies of the three conglomerates have been over the past 14 years or so. And yet, or perhaps precisely because of this, it feels good to back all three equally. All three clearly come from Graham and Doddsville and utilise the ‘Berkshire system’, so diversification feels good!

A few more comments on “normal times”: there are certainly never ‘normal times’, but the last 1.5 decades have been extreme for insurers and value investors in several ways: financial crisis, a long soft market followed by a very long hard market, growth outperforming value, the development of many successful disruptive companies (technology is historically more of an underperformer) dominating huge markets. Interest rates close to zero – with corresponding effects on the value of the float – and a sudden explosion of interest rates, no inflation followed by high inflation and now visibly more contained. In other words, we could do a lot wrong and a lot right. Timing was enormously important. Prem didn’t understand for a long time that ‘this time was indeed different’ in terms of the success of new players and their disruptive power (unlike Markel and Berkshire), but Fairfax capitalised perfectly on the hard market and the change in the interest rate regime (unlike MKL and BRK). Is it simply that sometimes you back the right horse and sometimes you don’t? Both between these three and on the sector side. Insurers with a value focus have certainly rarely had such bad times overall, caught between zero interest rates, a soft market with little float growth and ‘growth beating value’ and the establishment of new disruptive business models.

When I think about your thoughts on price trends, it occurs to me that the S&P500 has reached completely new (and yet reasonable) valuations over the last few decades. 10 and 20 years ago, the S&P500 had a P/E ratio of 20-21; today it is just under 31, i.e. 50% more expensive. At the same time, I suspect that the valuations 10 years ago for BRK, MKL and FFH have roughly not changed much – and 20 years ago BRK (and maybe Markel) will have been rather higher (I haven’t checked though and I might be wrong). It is understandable that in view of the ‘lost insurance decade’ insurers today are still valued lower than the average S&P500 company. and in this respect it is also logical that MKL, BRK and FFH have not shot the ball out of the park, as in many years before. As a sailor, you simply don’t get to your destination as quickly in a headwind. If float is worth nothing for many years, you also make hardly any insurance profits (high CR), inflation is low (i.e. low float growth) and as a value investor you don’t bet on the successfully growing disruptive companies that leave the rest of the S&P500 in the dust; isn’t it almost astonishing that you have generated decent returns after all? That sounds a bit milder than I feel, but you get the point. Would you bet on the next decade offering similarly poor conditions for insurers than in the 2010s? I wouldn’t and if it gets more normal, then the times should look better for all three insurers, especially for the smaller ones with a lot of float per equity. Anything is possible regarding the general conditions for the next decade, but the average is more likely than the extreme.

Good points. As far as the float issue is concerned, at least when talking about MKL’s intrinsic value, the profits from the insurance is already included in the operating earnings, so you can’t add back the underwriting profits to the value of their float. That would be double counting. Remember, in their case, they take operating earnings x 12 plus value of stocks and cash etc…

Your description of the 3 berk-alikes (or brk and 2 ba’s) is good and reminds us of how things change over time, things cycle in and out of favor etc. So your point is valid. But the only thing is, I base my comments on 10, 20 year figures, not 5 years, and 20 years is a very long time to underperform. I don’t remember if FFH, during the worst days, did all that poorly on 20 year figures.

One thing you can say is there is certainly end-point bias, meaning, maybe the S&P started at an especially low point 20 years ago, and may be nearing an extreme peak now, thus exaggerating the 20 year return (and vice-versa for the berk-alikes). That is certainly possible.

In any case, I too own all three of them as I do like their models, so it is like owning them for moral support, lol… Support the model, the people, trust the process, etc. But they are not all that big positions compared to your typical BRK owner…

Thanks to all who responded here!

My point about float was not so much related to your argument. Rather, I wanted to bring a completely different perspective, a different mental model, into the discussion. If you achieve an equity-like ROE on your equity alone (i.e. even without the profits from the insurance business) and achieve additional profits and investment results (and growth) from the insurance business (on no further equity) as a second pillar – then you have above-average returns by definition.

Of course, this mental model is not perfect, because an insurance business also requires equity (which in my mental model is incorrectly removed from the insurance business). In this respect, this perspective does not claim to be ‘100% correct’. But which one does? And aren’t mental models rather there to understand something superordinate?

And yet it is helpful in this respect, because for BRK, MKL and FFH, 1 (equity) + 1 (insurance business) is not simply 2, but something more – and that’s what Mr Market doesn’t understand when he looks at insurers. And if a value investing mindset should be helpful when investing equity, this might be even another factor for ‘more outcome’ as a result.

Great, article, thank you.

I understand Gayner wants the Buffett and Berkshire comparisons — the meetings in Omaha, the annual “reunion” in a basketball arena in Richmond, the long form interview availability, etc. However, Buffett is the greatest to ever do it. He is head and shoulders above everyone else. I don’t think it’s fair to expect either Markel’s stock or stock portfolio to perform similar to Berkshire’s.

I am long Markel, and I see no reason to change that view. Gayner seemingly makes mostly good decisions, and I have no doubt of his character. I think that’s a pretty good starting point.

I just dig deeper on Markel, BRK and the S&P500 regarding valuations 20 and 10 years ago etc. to see, if valuations of especially MKL were high etc.. so that the returns might be dragged lower for a high starting point. Here we go:

First thing that gets apparent in the table of the shareholder letters is the year end price of MKL between 2004 and 2010. It hasn’t changed, here‘s the list:

2004: 364 dollar (bvps: 168 dollar / 2.17 pb ratio)

2005: 317 dollar

2006: 480 dollar

2007: 491 dollar

2008: 299 dollar

2009: 340 dollar

2010: 378 dollar

2011: 415 dollar

2012: 433 dollar

2013: 580 dollar

2014: 683 dollar (bvps: 544 dollar / pb ratio: 1.26)

Then I researched the book valued end of the years and the price and added the bvps above. Don‘t forget: in reality the growth in book value is calculated on older numbers (the quarter before), so when comparing those numbers with todays numbers, my researched numbers should be adjusted maybe 4% higher, assuming a lag of a wuarter and growth of 16% in 2004.

So MKLs valuation 20 years ago (well not exactly 20 years ago, but that’s what I could find) was elevated. Within an old chart I found it looks like BRK was valued around 1.5 pb ratio end of 2004 and 1.6 pb ratio end of 2014.

Today BRK is valued at 1.7 and MKL 1.5

So all together BRK „now“ is valued nearly 13% higher then back in 2004, while MKL was valued 45% higher end of 2004. That‘s a big difference!

The pe ratio of the S&P500 stood nearly exactly at 20 both end of 2004 and end of 2014. And now it‘s at 28.4; so it’s valued over 40% higher today than 20 years ago, while Markel was valued 45% higher then – just the opposite.

Looking back just 10 years, both BRK and Markel are valued a bit higher now: MKL 20%, BRK 6%, compared to to the S&P500 being valued 45% higher.

The interesting questions in my eyes are:

– Does it make sense, that the S&P500 is valued 45% higher today with treasuries above 4% then they were with interest rates of 2% in 2014?

– Shouldn‘t help higher interest rates especially those companies with float, that’s going to be invested into bonds?

– Does it make sense, that the companies profitting the most from higher yields lag the valuation expansion of the average S&P500 company? Shouldn’t it be just the other way around?

Maybe that gives a little more context to the 20 years table.

Maybe it’s an idea to look at growth of intrinsic value too.

So here we go: Tilsons approach valuing BRK.a says it’s worth 742.000 dollar based on the actual numbers from end of 2024 and it was worth 103.000 dollar end of 2004. That‘s a CAGR of 10.4%

I don‘t have the same numbers from MKL. But back of the envelope I‘d say: Growth in book value should be a proxy, that underestimates the growth in intrinsic value. Why? Same reason as at Berkshire: The more wholly owned subsidiaries, the more widens the gap between intrinsic value and book value. Book value lags the intrinsic value each year a bit more, when buying more and more businesses not listed at the stock market.

MKLs bvps was around 150 dollar in 2004 and is 1.210 dollar today. So that‘s an 8-bagger (BRK was a 7-bagger), AND we know intrinsic value of MKL has grown stronger then that. So MKLs intrinsic value has done better.

But how much better? Gayner supports using nearly the same model then Tilson (Gayner likes to take three year averages though, to smooth out the ups and downs) and he guesses 2.610 dollar being the intrinsic value today. If I get it right, then those iv calculations of Gayner in fact are inflated a bit, as he uses the three year average and MKLs numbers grew over the last three years. So calculating only with2024 numbers iv should be higher.

Anyway: I don’t have the same numbers from 2004 here, so I can‘t calculate with the exact same formula and with that numbers from 2002, 2003, 2004.

But we could make a rough guess on what Buffett did: Until around 2010 he was clearly communicating, that bvps was a good proxy. And later on, when BRK had invested really big into wholly owned subsidiaries over years that changed, but he still was willing to buy at 1.1 pb ratio, so a lot of people believed, he would see BRKs intrinsic value around 1.5 pb ratio.

Okay, but other then BRK in 2010, MKL back in 2004 had no ventures at all. So we could assume 1.0 pb ratio being equal to intrinsic value back then. Or we could just build in a margin of safety and take that1.5 times bvps on the 2004 numbers even though BRK was earning loads of cash from its wholly owned subsidiaries, which MKL was clearly not. And don‘t forget: We have that second layer of margin of safety, as the 2.610 dollar of iv in fact are an average of the years 2022 to 2024; so the ending value in fact represents the iv of mid 2023, while we don‘t use an average of bvps from 2002 to 2004.

Okay, here we go. The numbers:

Iv Markel 2024: 2.610 dollar

Iv Markel 2004: 149 dollar (with 1.0 pb ratio) – CAGR 15.4%

Iv Markel 2004: 224 dollar (with 1.5 pb ratio) – CAGR 13.1%

So for Markel even building in some margin of safety, the iv seems to having outpaced BRKs CAGR of 10.4% by 2.7% per year or even 5.0% per year. That’s a lot.

I wasn‘t expecting such a clear outcome. Am I wrong here, did I miss something?