So we continue. Let’s see what he says in 1991:

BRK LTS 1991

Our outsized gain in book value in 1991 resulted from a phenomenon not apt to be repeated: a dramatic rise in the price-earnings ratios of Coca-Cola and Gillette. These two stocks accounted for nearly $1.6 billion of our $2.1 billion growth in net worth last year. When we loaded up on Coke three years ago, Berkshire’s net worth was $3.4 billion; now our Coke stock alone is worth more than that.

We all know what a home-run KO was, but I still had to go back and read that again about how BRK’s KO position is now worth more than the net worth of BRK three years before when they intitially bought KO.

So here’s a chart of KO from 1987 to the end of 1991. While many were waiting for next great depression to come, Buffett was scooping up KO, and not even at value prices.

Here’s the large holdings of BRK as of the end of 1991:

12/31/91

Shares Company Cost Market

------ ------- ---------- ----------

(000s omitted)

3,000,000 Capital Cities/ABC, Inc. ............ $ 517,500 $1,300,500

46,700,000 The Coca-Cola Company. .............. 1,023,920 3,747,675

2,495,200 Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. .... 77,245 343,090

6,850,000 GEICO Corp. ......................... 45,713 1,363,150

24,000,000 The Gillette Company ................ 600,000 1,347,000

31,247,000 Guinness PLC ........................ 264,782 296,755

1,727,765 The Washington Post Company ......... 9,731 336,050

5,000,000 Wells Fargo & Company 289,431 290,000

He talks about the difficulty of maintaining their book value growth over time. And here he makes one of those market forecasts that he does occasionally:

The third point incorporates two predictions: Charlie Munger, Berkshire’s Vice Chairman and my partner, and I are virtually certain that the return over the next decade from an investment in the S&P index will be far less than that of the past decade, and we are dead certain that the drag exerted by Berkshire’s expanding capital base will substantially reduce our historical advantage relative to the index.

Making the first prediction goes somewhat against our grain: We’ve long felt that the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good. Even now, Charlie and I continue to believe that short-term market forecasts are poison and should be kept locked up in a safe place, away from children and also from grown-ups who behave in the market like children. However, it is clear that stocks cannot forever overperform their underlying businesses, as they have so dramatically done for some time, and that fact makes us quite confident of our forecast that the rewards from investing in stocks over the next decade will be significantly smaller than they were in the last. Our second conclusion – that an increased capital base will act as an anchor on our relative performance – seems incontestable. The only open question is whether we can drag the anchor along at some tolerable, though slowed, pace.

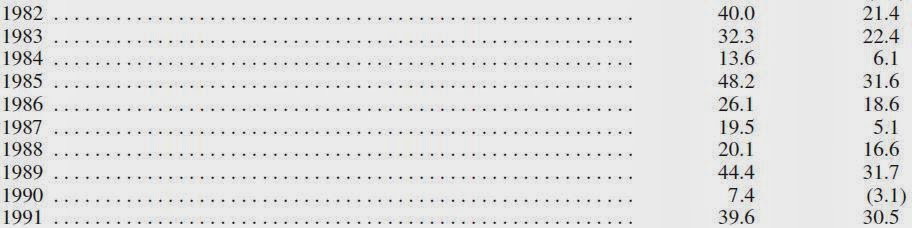

So let’s take a look at this. In the decade through 1991, this is what the BRK and the S&P 500 (including dividends) did. This is from the 2013 annual report:

BRK book value grew +28.4%/year in the 10 years through 1991 versus +17.5%/year for the S&P 500 index.

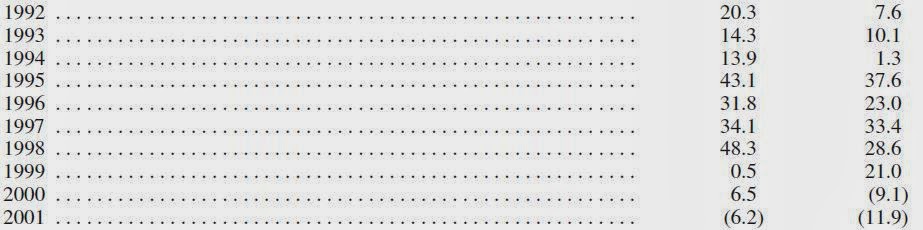

Now let’s see if Buffett’s prediction held:

In the next decade after his comment BRK BPS grew +19.4%/year and the S&P 500 index returned +12.9%/year.

So he was exactly right. The returns over the following decade were lower than the previous ten years. But again, here’s the deal. Did Buffett lighten up on stocks or sell out to wait for a better opportunity (like many investors did all throughout the late 80’s and throughout the 90’s)? Nope. He managed his expectations, but didn’t do anything to exploit his view on the market.

It’s hard to believe now, but in much of the 1990’s, many people were still shaken by Black Monday and were afraid of getting back into stocks; they thought another crash was around the corner (sound familiar? Right now feels sort of like the 1990’s; people still suffering from (PCSD) Post-Crash (or Crisis)-Stress-Disorder.

BRK LTS 1993

In 1993, Buffett talks about how intrinsic value and market price may not move together in lock step over the short term (but will over the long term). He mentions how Coke and Gillette stock prices far outpaced their businesses up to 1991, but have lagged in the couple of years to 1993. But he said:

Let me add a lesson from history: Coke went public in 1919 at $40 per share. By the end of 1920 the market, coldly reevaluating Coke’s future prospects, had battered the stock down by more than 50%, to $19.50. At year-end 1993, that single share, with dividends reinvested, was worth more than $2.1 million. As Ben Graham said: “In the short-run, the market is a voting machine – reflecting a voter-registration test that requires only money, not intelligence or emotional stability – but in the long-run, the market is a weighing machine.

And about the low amount of activity in the equity porfolio, he says:

Considering the similarity of this year’s list and the last, you may decide your management is hopelessly comatose. But we continue to think that it is usually foolish to part with an interest in a business that is both understandable and durably wonderful. Business interests of that kind are simply too hard to replace.

Interestingly, corporate managers have no trouble understanding that point when they are focusing on a business they operate: A parent company that owns a subsidiary with superb long-term economics is not likely to sell that entity regardless of price. “Why,” the CEO would ask, “should I part with my crown jewel?” Yet that same CEO, will offhandedly – and even impetuously – move from business to business when presented with no more than superficial arguments by his broker for doing so. The worst of these is perhaps, “You can’t go broke taking a profit.” Can you imagine a CEO using this line to urge his board to sell a star subsidiary? In our view, what makes sense in business also makes sense in stocks: An investor should ordinarily hold a small piece of an outstanding business with the same tenacity that an owner would exhibit if he owned all of that business.

Here’s another great lesson on investing using Coke as an example:

Earlier I mentioned the financial results that could have been achieved by investing $40 in The Coca-Cola Co. in 1919. In 1938, more than 50 years after the introduction of Coke, and long after the drink was firmly established as an American icon, Fortune did an excellent story on the company. In the second paragraph the writer reported: “Several times every year a weighty and serious investor looks long and with profound respect at Coca-Cola’s record, but comes regretfully to the conclusion that he is looking too late. The specters of saturation and competition rise before him.”

Yes, competition there was in 1938 and in 1993 as well. But it’s worth noting that in 1938 The Coca-Cola Co. sold 207 million cases of soft drinks (if its gallonage then is converted into the 192-ounce cases used for measurement today) and in 1993 it sold about 10.7 billion cases, a 50-fold increase in physical volume from a company that in 1938 was already dominant in its very major industry. Nor was the party over in 1938 for an investor: Though the $40 invested in 1919 in one share had (with dividends reinvested) turned into $3,277 by the end of 1938, a fresh $40 then invested in Coca-Cola stock would have grown to $25,000 by year-end 1993.

I can’t resist one more quote from that 1938 Fortune story: “It would be hard to name any company comparable in size to Coca-Cola and selling, as Coca-Cola does, an unchanged product that can point to a ten-year record anything like Coca-Cola’s.” In the 55 years that have since passed, Coke’s product line has broadened somewhat, but it’s remarkable how well that description still fits.

Charlie and I had decided long ago that in an investment lifetime it’s just too hard to make hundreds of smart decisions. That judgement became ever more compelling as Berkshire’s capital mushroomed and the universe of investments that could significantly affect our results shrank dramatically. Therefore, we adopted a strategy that required our being smart – and not too smart at that – only a very few times. Indeed, we’ll now settle for one good idea a year. (Charlie says it’s my turn.)

There’s more about investing in the 1993 letter which talks about the benefits of focusing investments rather than diversifying, and what real risk in investing is (and it’s not volatility or beta!).

BRK 1994 LTS

1994 was another eventful year in the market with a bond market bubble popping. Here, Buffett talks about investing again and really gets down to what this series is sort of all about:

We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts, which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen. Thirty years ago, no one could have foreseen the huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%.

But, surprise – none of these blockbuster events made the slightest dent in Ben Graham’s investment principles. Nor did they render unsound the negotiated purchases of fine businesses at sensible prices. Imagine the cost to us, then, if we had let fear of unknowns cause us to defer or alter the deployment of capital. Indeed, we have usually made our best purchases when apprehensions about some macro event were at a peak. Fear is the foe of the faddist, but friend of the fundamentalist.

A different set of major shocks is sure to occur in the next 30 years. We will neither try to predict these nor profit from them. If we can identify businesses similar to those we have purchased in the past, external surprises will have little effect on our long-term results.

Later on he talks about pricing investments and not timing them.

We purchased National Indemnity in 1967, See’s in 1972, Buffalo News in 1977, Nebraska Furniture Mart in 1983, and Scott Fetzer in 1986 because those are the years they became available and because we thought the prices they carried were acceptable. In each case, we pondered what the business was likely to do, not what the Dow, the Fed, or the economy might do. If we see this approach as making sense in the purchase of businesses in their entirety, why should we change tack when we are purchasing small pieces of wonderful businesses in the stock market?

And if he is not going to sell these businesses when market valuations are high, why would he sell any of his permanent stock holdings? They need to be attractively priced with a margin of safety for purchase, but not necessarily for them to be held.

BRK 1995 LTS

In 1995, Buffett talks about American Express, Capital Cities and Disney (he actually bought shares in the market before the deal closed) and other investments, but here’s an interesting story that he tells:

One more bit of history: I first became interested in Disney in 1966, when its market valuation was less than $90 million, even though the company had earned around $21 million pre-tax in 1965 and was sitting with more cash than debt. At Disneyland, the $17 million Pirates of the Caribbean ride would soon open. Imagine my excitement – a company selling at only five times rides!

Duly impressed, Buffett Partnership Ltd. bought a significant amount of Disney stock at a split-adjusted price of 31 cents per share. That decision may appear brilliant, given that the stock now sells for $66. But your Chairman was up to the task of nullifying it: In 1967 I sold out at 48 cents per share.

If he had continued to own Disney from 1966 to 1995, he would have earned 20%/year for 29 years!

BRK LTS 1996

In the 1996 letter, Buffett writes:

I was recently studying the 1896 report of Coke (and you think that you are behind in your reading!). At that time Coke, though it was already the leading soft drink, had been around for only a decade. But its blueprint for the next 100 years was already drawn. Reporting sales of $148,000 that year, Asa Candler, the company’s president, said: “We have not lagged in our efforts to go into all the world teaching that Coca-Cola is the article, par excellence, for the health and good feeling of all people.” Though “health” may have been a reach, I love the fact that Coke still relies on Candler’s basic theme today – a century later. Candler went on to say, just as Roberto could now, “No article of like character has ever so firmly entrenched itself in public favor.” Sales of syrup that year, incidentally, were 116,492 gallons versus about 3.2 billion in 1996.

So don’t you wish you can read the 1896 annual report too? Don’t you wish you can show your kids or grandkids for educational purposes? This is why I mentioned the idea of a Warren Buffett Library of Corporate Annual Reports.

The 1996 letter has a lot of stuff including advice to those who want to invest for themselves. But since I am only looking for specific views on the market, or his actions at market extremes (in terms of valuation), let’s move on.

BRK LTS 1997

The 1997 letter is very interesting for a couple of reasons. First of all, Buffett for the first time mentions some unconventional investments. He also mentions selling some stocks to adjust the stock-bond ratio of the portfolio based on expected returns. Buffett is not known for setting target ratios for that, but I suppose there was some adjustments done there. This was the late 90’s after the 1996, Greenspan “Irrational Exuberance” speech.

Unconventional Commitments

When we can’t find our favorite commitment — a well-run and sensibly-priced business with fine economics — we usually opt to put new money into very short-term instruments of the highest quality. Sometimes, however, we venture elsewhere. Obviously we believe that the alternative commitments we make are more likely to result in profit than loss. But we also realize that they do not offer the certainty of profit that exists in a wonderful business secured at an attractive price. Finding that kind of opportunity, we know that we are going to make money — the only question being when. With alternative investments, we think that we are going to make money. But we also recognize that we will sometimes realize losses, occasionally of substantial size.

We had three non-traditional positions at year-end. The first was derivative contracts for 14.0 million barrels of oil, that being what was then left of a 45.7 million barrel position we established in 1994-95. Contracts for 31.7 million barrels were settled in 1995-97, and these supplied us with a pre-tax gain of about $61.9 million. Our remaining contracts expire during 1998 and 1999. In these, we had an unrealized gain of $11.6 million at year-end. Accounting rules require that commodity positions be carried at market value. Therefore, both our annual and quarterly financial statements reflect any unrealized gain or loss in these contracts. When we established our contracts, oil for future delivery seemed modestly underpriced. Today, though, we have no opinion as to its attractiveness.

Our second non-traditional commitment is in silver. Last year, we purchased 111.2 million ounces. Marked to market, that position produced a pre-tax gain of $97.4 million for us in 1997. In a way, this is a return to the past for me: Thirty years ago, I bought silver because I anticipated its demonetization by the U.S. Government. Ever since, I have followed the metal’s fundamentals but not owned it. In recent years, bullion inventories have fallen materially, and last summer Charlie and I concluded that a higher price would be needed to establish equilibrium between supply and demand. Inflation expectations, it should be noted, play no part in our calculation of silver’s value.

Finally, our largest non-traditional position at yearend was $4.6 billion, at amortized cost, of long-term zero-coupon obligations of the U.S. Treasury. These securities pay no interest. Instead, they provide their holders a return by way of the discount at which they are purchased, a characteristic that makes their market prices move rapidly when interest rates change. If rates rise, you lose heavily with zeros, and if rates fall, you make outsized gains. Since rates fell in 1997, we ended the year with an unrealized pre-tax gain of $598.8 million in our zeros. Because we carry the securities at market value, that gain is reflected in yearend book value.

In purchasing zeros, rather than staying with cash-equivalents, we risk looking very foolish: A macro-based commitment such as this never has anything close to a 100% probability of being successful. However, you pay Charlie and me to use our best judgment — not to avoid embarrassment — and we will occasionally make an unconventional move when we believe the odds favor it. Try to think kindly of us when we blow one. Along with President Clinton, we will be feeling your pain: The Munger family has more than 90% of its net worth in Berkshire and the Buffetts more than 99%.

This is certainly a rare move; I don’t remember any other commodity investments that he has made like this. But he does move into areas when there is an opportunity, like junk bonds and writing derivatives puts on global indices. But this is clearly not a major contributor to the earnings at BRK.

Here is a comment that sounds a little unusual, though. So if you want to jump up and say “Aha! Buffett is a market timer after all!”, well, do so now.

We made net sales during the year that amounted to about 5% of our beginning portfolio. In these, we significantly reduced a few of our holdings that are below the $750 million threshold for itemization, and we also modestly trimmed a few of the larger positions that we detail. Some of the sales we made during 1997 were aimed at changing our bond-stock ratio moderately in response to the relative values that we saw in each market, a realignment we have continued in 1998.

But still, this is a minor adjustment in the portfolio. I’ve never heard of BRK wanting to maintain any target bond-stock ratio, so maybe the terminology is misleading.

And here is his comment (that he occasionally makes) on the level of the stock market:

Though we don’t attempt to predict the movements of the stock market, we do try, in a very rough way, to value it. At the annual meeting last year, with the Dow at 7,071 and long-term Treasury yields at 6.89%, Charlie and I stated that we did not consider the market overvalued if 1) interest rates remained where they were or fell, and 2) American business continued to earn the remarkable returns on equity that it had recently recorded. So far, interest rates have fallen — that’s one requisite satisfied — and returns on equity still remain exceptionally high. If they stay there — and if interest rates hold near recent levels — there is no reason to think of stocks as generally overvalued. On the other hand, returns on equity are not a sure thing to remain at, or even near, their present levels.

In the summer of 1979, when equities looked cheap to me, I wrote a Forbes article entitled “You pay a very high price in the stock market for a cheery consensus.” At that time skepticism and disappointment prevailed, and my point was that investors should be glad of the fact, since pessimism drives down prices to truly attractive levels. Now, however, we have a very cheery consensus. That does not necessarily mean this is the wrong time to buy stocks: Corporate America is now earning far more money than it was just a few years ago, and in the presence of lower interest rates, every dollar of earnings becomes more valuable. Today’s price levels, though, have materially eroded the “margin of safety” that Ben Graham identified as the cornerstone of intelligent investing.

Despite his “unconventional commitments” and the adjustment of the “stock-bond ratio”, BRK’s portfolio is pretty much unchanged. He continues to own the wholly owned businesses and the core holdings in the equity portfolio.

BRK LTS 1998

Investments

Below we present our common stock investments. Those with a market value of more than $750 million are itemized.

|

|

|

12/31/98

|

|||

|

Shares

|

Company

|

Cost*

|

Market

|

||

|

|

|

(dollars in millions)

|

|||

|

50,536,900

|

American Express Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

$1,470

|

$ 5,180

|

||

|

200,000,000

|

The Coca-Cola Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

1,299

|

13,400

|

||

|

51,202,242

|

The Walt Disney Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

281

|

1,536

|

||

|

60,298,000

|

Freddie Mac . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

308

|

3,885

|

||

|

96,000,000

|

The Gillette Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

600

|

4,590

|

||

|

1,727,765

|

The Washington Post Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

11

|

999

|

||

|

63,595,180

|

Wells Fargo & Company . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

392

|

2,540

|

||

|

|

Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

2,683

|

5,135

|

||

|

|

Total Common Stocks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

$ 7,044

|

$ 37,265

|

||

|

=====

|

=====

|

||||

During the year, we slightly increased our holdings in American Express, one of our three largest commitments, and left the other two unchanged. However, we trimmed or substantially cut many of our smaller positions. Here, I need to make a confession (ugh): The portfolio actions I took in 1998 actually decreased our gain for the year. In particular, my decision to sell McDonald’s was a very big mistake. Overall, you would have been better off last year if I had regularly snuck off to the movies during market hours.

The total cost of the equity portfolio in 1997 was $7.2 billion versus $7.0 billion in 1998, so if this is the right way to think about it, the trimming of the stock portfolio wasn’t much; more like fine tuning.

At yearend, we held more than $15 billion in cash equivalents (including high-grade securities due in less than one year). Cash never makes us happy. But it’s better to have the money burning a hole in Berkshire’s pocket than resting comfortably in someone else’s. Charlie and I will continue our search for large equity investments or, better yet, a really major business acquisition that would absorb our liquid assets. Currently, however, we see nothing on the horizon.

As there are no opportunities, BRK sits on cash. But again, sitting on cash and letting it accumulate is not the same as getting out of stocks because they are fully priced. They need a discount to intrinsic value and margin of safety to buy stock, but not necessarily to own them (which Buffett said they will do even if they get substantially overvalued, at least for their permanent holdings).

And then he mentions the unconventional commitments he wrote about in the 1997 letter:

Last year I deviated from my standard practice of not disclosing our investments (other than those we are legally required to report) and told you about three unconventional investments we had made. There were several reasons behind that disclosure. First, questions about our silver position that we had received from regulatory authorities led us to believe that they wished us to publicly acknowledge this investment. Second, our holdings of zero-coupon bonds were so large that we wanted our owners to know of this investment’s potential impact on Berkshire’s net worth. Third, we simply wanted to alert you to the fact that we sometimes do make unconventional commitments.

This makes you wonder what else they have done over the years and haven’t been disclosed. But that’s OK because most of the wealth at BRK was created by the activities that are disclosed (profit of private businesses, large equity portfolio etc.)

BRK 1999 LTS

So 1999 was a relatively bad year for BRK, with BPS flat versus the 20% gain in the S&P 500 index. And here he expresses his confidence that they will do moderately better than the index (but not as much as in the past due to size etc.) and reservations about the stock market:

Our optimism about Berkshire’s performance is also tempered by the expectation — indeed, in our minds, the virtual certainty — that the S&P will do far less well in the next decade or two than it has done since 1982. A recent article in Fortune expressed my views as to why this is inevitable, and I’m enclosing a copy with this report.

And here’s the discussion about stock price levels (emphasis mine):

Right now, the prices of the fine businesses we already own are just not that attractive. In other words, we feel much better about the businesses than their stocks. That’s why we haven’t added to our present holdings. Nevertheless, we haven’t yet scaled back our portfolio in a major way: If the choice is between a questionable business at a comfortable price or a comfortable business at a questionable price, we much prefer the latter. What really gets our attention, however, is a comfortable business at a comfortable price.

Our reservations about the prices of securities we own apply also to the general level of equity prices. We have never attempted to forecast what the stock market is going to do in the next month or the next year, and we are not trying to do that now. But, as I point out in the enclosed article, equity investors currently seem wildly optimistic in their expectations about future returns.

We see the growth in corporate profits as being largely tied to the business done in the country (GDP), and we see GDP growing at a real rate of about 3%. In addition, we have hypothesized 2% inflation. Charlie and I have no particular conviction about the accuracy of 2%. However, it’s the market’s view: Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) yield about two percentage points less than the standard treasury bond, and if you believe inflation rates are going to be higher than that, you can profit by simply buying TIPS and shorting Governments.

If profits do indeed grow along with GDP, at about a 5% rate, the valuation placed on American business is unlikely to climb by much more than that. Add in something for dividends, and you emerge with returns from equities that are dramatically less than most investors have either experienced in the past or expect in the future. If investor expectations become more realistic — and they almost certainly will — the market adjustment is apt to be severe, particularly in sectors in which speculation has been concentrated.

Berkshire will someday have opportunities to deploy major amounts of cash in equity markets — we are confident of that. But, as the song goes, “Who knows where or when?” Meanwhile, if anyone starts explaining to you what is going on in the truly-manic portions of this “enchanted” market, you might remember still another line of song: “Fools give you reasons, wise men never try.”

Again, he sees the market way too high and expectations way too high and yet he makes very little changes in the equity portfolio. We can argue that he doesn’t own the bubbled up internet and other technology stocks, but we do know that Coke was pretty expensive as was Gillette. He later does regret not selling the more expensive things, though.

Fortune Article 1999

So now let’s get to that 1999 article where he warned of a high stock market. Here’s the link if you haven’t read it. It’s very good. You can read it here.

I’m not going to go back and get figures as we all know the market did phenomenally well in every time period up to 1999 (OK, it went up more than 24% per year from the end of 1981 through 1999 including dividends).

Buffett was alarmed that polls showed investors expecting returns of 22% (inexperienced investors) and 12% (experienced investors) over time going forward.

The gist of this article is that this is way too high an expectation.

First he says that valuation won’t tell you what the market will do in the short term, but can give you an idea what to expect over the long term:

Investors in stocks these days are expecting far too much, and I’m going to explain why. That will inevitably set me to talking about the general stock market, a subject I’m usually unwilling to discuss. But I want to make one thing clear going in: Though I will be talking about the level of the market, I will not be predicting its next moves. At Berkshire we focus almost exclusively on the valuations of individual companies, looking only to a very limited extent at the valuation of the overall market. Even then, valuing the market has nothing to do with where it’s going to go next week or next month or next year, a line of thought we never get into. The fact is that markets behave in ways, sometimes for a very long stretch, that are not linked to value. Sooner or later, though, value counts. So what I am going to be saying–assuming it’s correct–will have implications for the long-term results to be realized by American stockholders.

And in summary after a great explanation, he says:

Let me summarize what I’ve been saying about the stock market: I think it’s very hard to come up with a persuasive case that equities will over the next 17 years perform anything like–anything like–they’ve performed in the past 17. If I had to pick the most probable return, from appreciation and dividends combined, that investors in aggregate–repeat, aggregate–would earn in a world of constant interest rates, 2% inflation, and those ever hurtful frictional costs, it would be 6%. If you strip out the inflation component from this nominal return (which you would need to do however inflation fluctuates), that’s 4% in real terms. And if 4% is wrong, I believe that the percentage is just as likely to be less as more.

So here’s the key point, I think. He warns people (who are expecting high returns in the stock market) that returns going forward are not going to be as high as they think. His best guess of returns in the stock market going forward is 6%/year, not too far from long term bond yields at the time, I think.

This is not a warning that a crash is imminent, even though he expects a correction when people’s expectations are adjusted down. Even at the then prices in 1999, he was expecting 6%/year returns.

So this is not really a “get out of stocks now!” warning or anything like that. It’s more of an issue of managing expections (as he would have no idea when the market would decline). I guess it was a strong warning to get out of the more speculative areas of the market.

But this sort of explains why he wasn’t rushing to sell his stocks; he was still expecting 6%/year over time in the stock market. That’s no reason to run to the hills.

It turns out that since 1999 through the end of 2013, the S&P 500 index returned only 3.6%/year. He did say that returns could just as likely to be less as more.

BRK LTS 2000

He is still lukewarm on the market, but maintains BRK’s positions:

Another negative ¾ which has persisted for several years ¾ is that we see our equity portfolio as only mildly attractive. We own stocks of some excellent businesses, but most of our holdings are fully priced and are unlikely to deliver more than moderate returns in the future. We’re not alone in facing this problem: The long-term prospect for equities in general is far from exciting.

BRK LTS 2001

We made few changes in our portfolio during 2001. As a group, our larger holdings have performed poorly in the last few years, some because of disappointing operating results. Charlie and I still like the basic businesses of all the companies we own. But we do not believe Berkshire’s equity holdings as a group are undervalued.

Our restrained enthusiasm for these securities is matched by decidedly lukewarm feelings about the prospects for stocks in general over the next decade or so. I expressed my views about equity returns in a speech I gave at an Allen and Company meeting in July (which was a follow-up to a similar presentation I had made two years earlier) and an edited version of my comments appeared in a December 10th Fortune article. I’m enclosing a copy of that article. You can also view the Fortune version of my 1999 talk at our website www.berkshirehathaway.com.

Charlie and I believe that American business will do fine over time but think that today’s equity prices presage only moderate returns for investors. The market outperformed business for a very long period, and that phenomenon had to end. A market that no more than parallels business progress, however, is likely to leave many investors disappointed, particularly those relatively new to the game.

Here’s one for those who enjoy an odd coincidence: The Great Bubble ended on March 10, 2000 (though we didn’t realize that fact until some months later). On that day, the NASDAQ (recently 1,731) hit its all-time high of 5,132. That same day, Berkshire shares traded at $40,800, their lowest price since mid-1997.

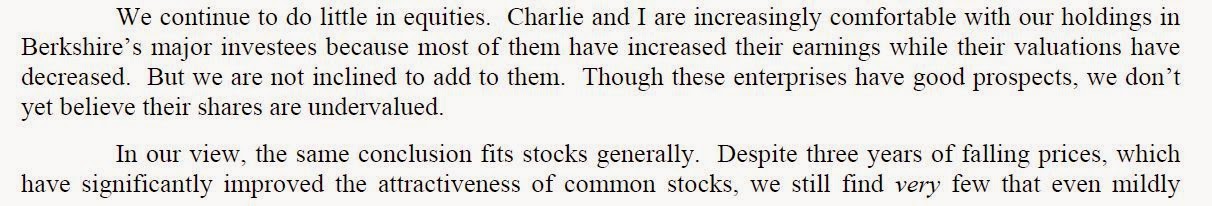

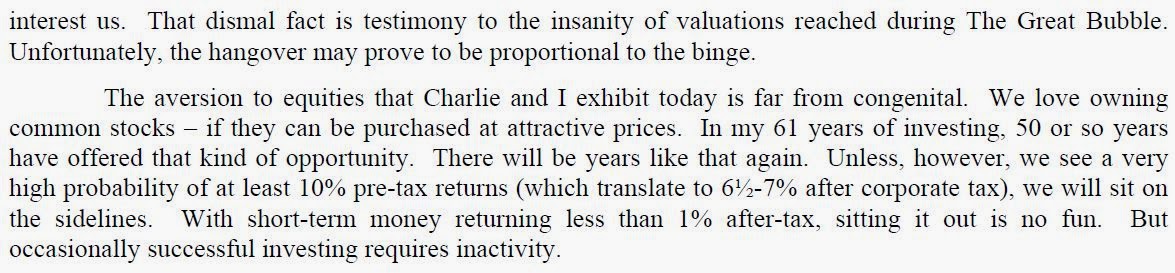

BRK LTS 2002

Here is the 10% pre-tax return benchmark. We’ve all heard it at annual meetings and such, but I don’t recall seeing this in the annual report (even though I’ve read all of them before; I didn’t remember that).

BRK LTS 2003

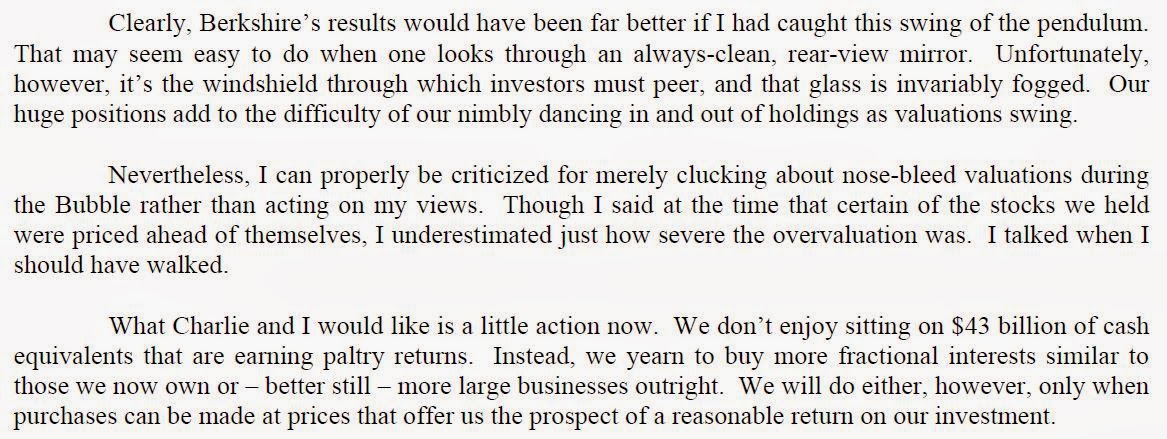

And here he admits a “big mistake” in not selling some large holdings that got way too expensive:

BRK LTS 2004

Buffett still has trouble finding places to invest:

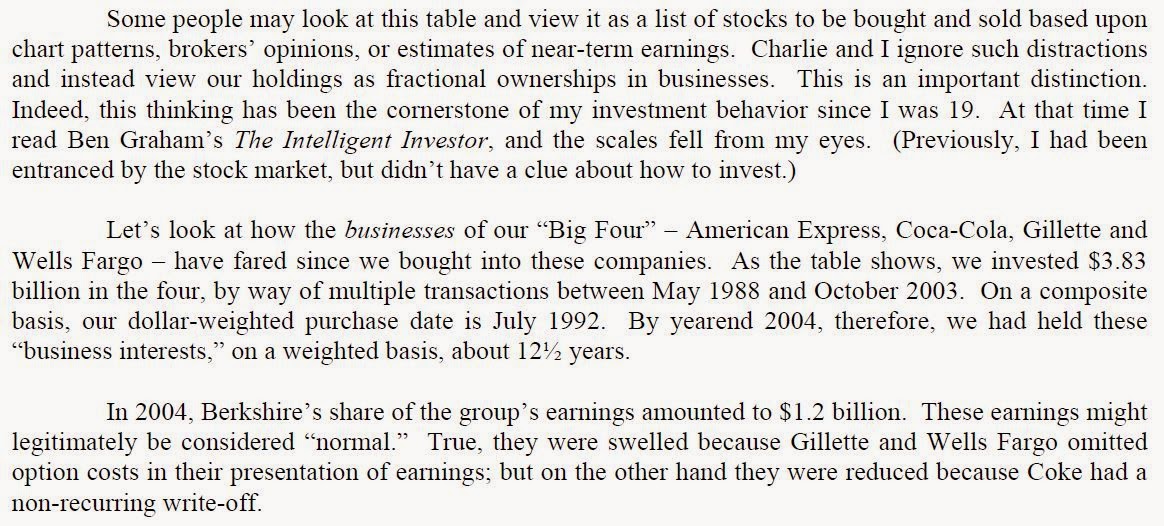

And he discusses why, despite such a strong stock market over the years, many investors don’t do too well:

He does say that if people want to really time their participation in equities, that they should buy low and sell high. But from what I’ve seen, people do tend to buy low but then sell way too soon as soon as they think the market is fully priced. So doing that can be difficult too. When are people greedy, and when are they fearful?

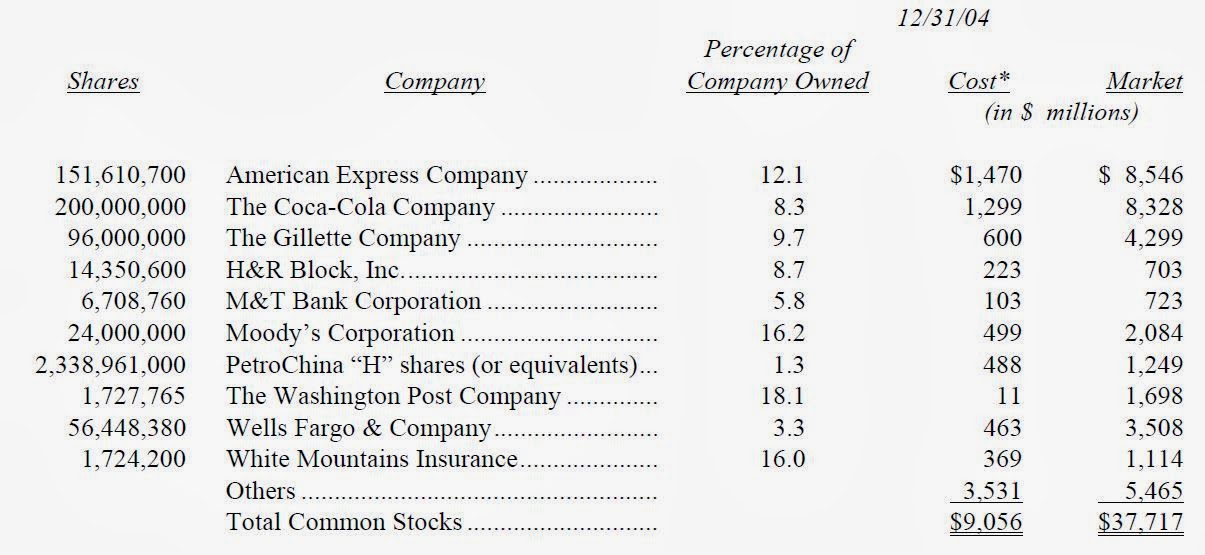

Here is the large equity holdings as of 2004:

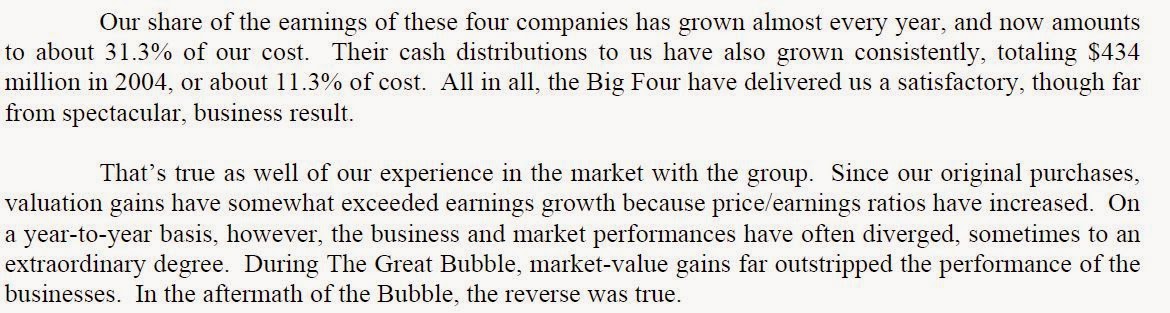

And he discusses his long term holdings and contemplates the idea of BRK catching the swings of the pendulum. But he does still regret not selling things during the Great Bubble.

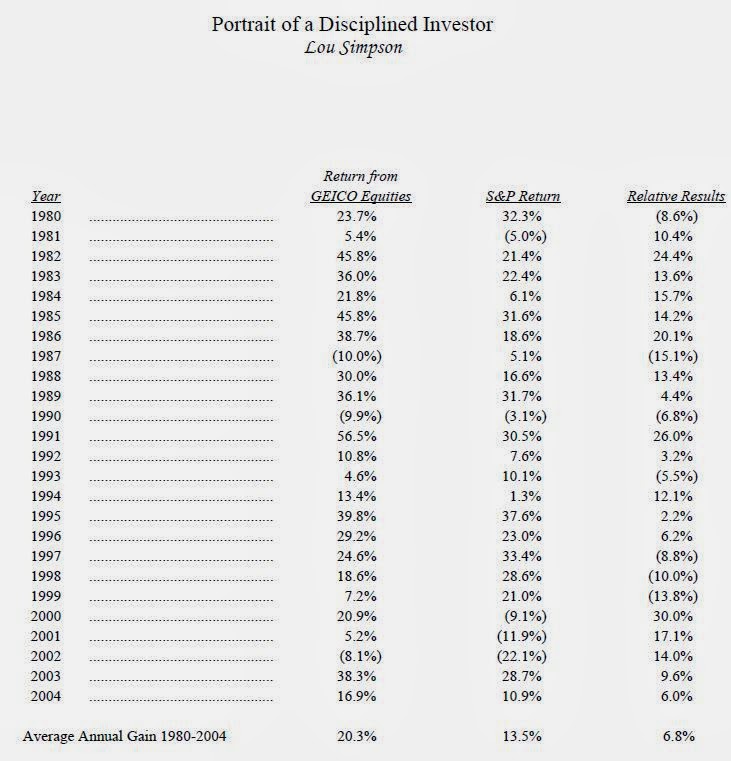

This isn’t really related to our topic, but it’s a nice table so I just threw it in here:

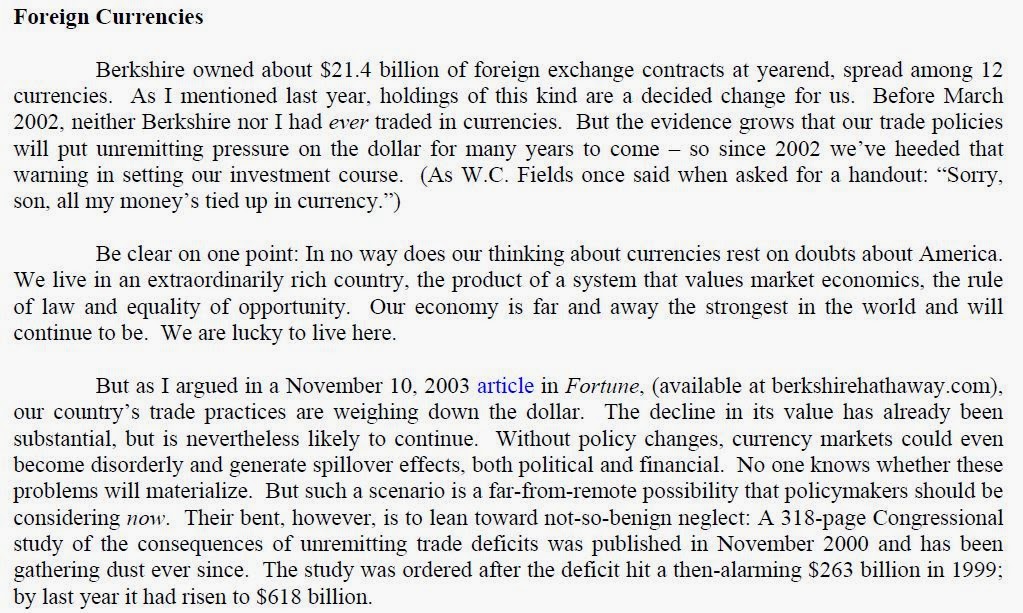

Aha, and here again is Buffett playing with the macro:

It is another one of his unconventional commitments, I suppose. I don’t think it was a major factor either way, and I remember he said that he put on these positions at positive carry so he was being paid to carry the position; he wouldn’t hold the position if he had to pay to maintain it. And in fact, I think he did say he unwound it when it was no longer positive carry.

Conclusion for 1991-2004

OK, so again this is getting too long so I will chop it off here and continue hopefully the last segment in 2004-2013. There is a lot of stuff including the 2006/2007 bubble and then the Great Recession, so reviewing his comments on the markets would be very interesting.

Since he really regrets not selling stuff during the Great Bubble, it will be interesting to see how his actions during the 2006/2007 bubble changed from that experience (or not changed).

Anyway, stay tuned…

Thank you very much for posting! Wonderful blog!

As for the whole topic and last segment please consider this:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/17/opinion/17buffett.html

"So … I’ve been buying American stocks. This is my personal account I’m talking about, in which I previously owned nothing but United States government bonds. (This description leaves aside my Berkshire Hathaway holdings, which are all committed to philanthropy.) If prices keep looking attractive, my non-Berkshire net worth will soon be 100 percent in United States equities."

So personally Buffett was owning bonds, perhaps with not so very impressive yields and what is even more interesting, at the same time, in 2006-2007, BRK started for the first time since 2003 (at that time Buffett was saying that equities still are not attractive) to put more and more money into equities: Kraft, Burlington, J&J, US Bancorp. So this is interesting how to reconcile this and maybe this is different level of required returns, maybe size/ability to move problems in case of BRK and it is understandable. Anyway, if the best place for the long term is equities and valuations was not extremely high (new holdings for BRK) how is that happened, that personal portfolio (perhaps supposed to be even more on auto pilot mode) was all in bonds?

Thank you!

That's a very good point. I would guess that for Buffett, bonds is the default position in his personal account. He already has (or had) 99% in BRK, so whatever he does in the persnal account is not going to move the meter of his personal wealth. If he was going to work to get richer, he should focus on BRK, not his PA.

Having said that, like the Korean stocks he bought a while ago in his PA, I think there are times when things get so silly and out of whack that he just moves his PA into it. Recently he owns JPM. (or maybe that's what he bought in 2008).

So that's not really market timing or anything like that at all. It's just a one-time thing (that happens occasionally).

I think that's the same with DJCO. If Munger was trying to create a good 'track record' as an investor, sitting on cash all that time is not the way to do it. I think even in that case, Munger wasn't treating DJCO as his personal hedge fund. But when things got so silly and out of whack, he just jumped on it becuase the cash was there.