I’ve read the 1934, 1940 and 1988 editions of Securities Analysis but haven’t read the 1951 and 1962 editions. For whatever reason, they slipped through the cracks. I really love the 1934 edition because it is the first edition and really digs into what went wrong in the 1920s and early 1930s (sounds exactly like the 1990s bubble), and the 1940 edition.

I think Buffett has said that the 1940 edition is his favorite. He said he has read it at least four times over the years. A sixth edition was published recently with comments by some of the current great investors and those ‘essays’ alone are worth the price of the book. The sixth edition is just a reissue of the 1940 edition (updated) with these essays added.

The commentators are:

- Seth Klarman

- James Grant

- Roger Lowenstein

- Howard Marks

- J. Ezra Merkin (?!)

- Bruce Berkowitz

- Glenn Greenberg

- Bruce Greenwald

- David Abrams

- Thomas Russo

Anyway, here are the links to the various editions (of course, from the Brooklyn investor store; I just set up this bookstore for fun. I wanted to understand how this stuff works (after following Amazon for so many years) and did it out of curiosity, plus I find myself recommending the same books over and over to people so figured I would put it all up somewhere. I haven’t really finished stocking it up and organizing it, though).

1934 Edition

Sixth Edition (1940 reissue)

1951 Edition

1962 Edition

If you haven’t read any of them and only had to read one, I would say start with the Sixth Edition (The 1988 edition was not written by Graham).

1951 Edition

Anyway, so I started reading the 1951 edition and in the preface dated October 1951, there was a paragraph that struck me as relevant to today (well, everything he says is still relevant today):

This preface is being written when the possibility of a third world war weighs heavily in all our minds. We need to say only a word about this unhappy subject in relation to our present work. The effect of such a war upon ourselves and our institutions is incalculable. But in the field of securities analysis we need consider only its bearing on the choice between various securities and between securities and (paper) money. It seems sufficient to observe that since war and inflation are inseparable, paper money and securities payable in specific amounts of paper money would seem to offer less financial or basic protection than soundly chosen common stocks, representing ownership of tangible, productive property.

And in the footnote, there was an excerpt from an essay Graham wrote for the Analysts Journal in the first quarter of 1951 titled The War and Stock Values.

Here is a quote from there:

Stock prices as a whole may be expected to rise, sooner or later, to reflect this cheapening of the dollar. The course of the stock market from 1900 to date (1951) shows a fairly close over-all correspondence between the rise in stocks and the general prices, although there have been significant divergences for fairly long periods.

This is relevant today because most people seem to fear now high inflation due to all the pump-priming around the world. This is not news to stock investors; many believe that stocks are better than cash and bonds, but others are worried that high inflation will cause stock prices to go down; they think they should wait by holding cash (despite inflation risk), gold or look into investing in ‘hard’ assets like real estate.

Hard Assets or Stocks?

I wrote a lot about what I think of gold here so I’ll talk about other assets. There is somewhat of a boom in farm land around the world with purely financial buyers bidding up prices. The story makes a lot of sense; there will be inflation in the future so own hard assets. Food demand will continue to grow on increasing population so farmland prices will go up.

But it’s important to remember (and nobody really talks about anymore) that the housing bubble in the U.S. was driven largely by people wanting to own a ‘hard’ asset. They got killed in stocks in the 2000 internet bubble. They vowed, no more stocks! And they rushed into real estate. It’s a hard asset, right? It will hold it’s value. The Fed will always print more money at every economic downtick. The government will keep spending money. Inflation is inevitable. So why not own houses and real estate? Land bank stocks boomed too back then. They don’t make more land, right? But they do keep printing more money.

So it made perfect sense. Buy houses, land, land bank stocks etc. And what’s more, you can borrow to do so. Borrowing money is shorting the U.S. dollar. And sometimes you can do it with positive carry or zero carry (cash savings or rental income pays interest and other expenses so you get the rise in prices for free).

This was a major factor in people rushing into real estate, I think.

And there are people driven to certain investments today for the same reason and I am a bit skeptical of them.

Stocks are Real Assets Too

People tend to brush off stocks as a piece of paper and forget that it’s a partial ownership of real assets, or “tangible, productive property” as Graham called it. Of course, this is not true for all stocks. As I mentioned in a post a while back, Coca-Cola has done really well over time despite the inflation that has occured in the past century. As Graham says, stock prices eventually catch up to the rise in general price levels. (I wrote about KO and inflation here)

If a business has a good product, good management, good business etc., then inflation won’t be much of a problem. The only problem is that if inflation ticks up, stock prices may go down in the short term (Earnings may go down too, but if it’s a good business, they will be able to reprice and do well over time).

I think this is what most investors worry about. They remember stocks at 7x p/e back in the late 1970s and think it can go back to that level when high inflation inevitably comes.

In the above mentioned The War and Stock Values essay, Graham wrote:

War conditions could be destructive to stock values but the mere possibility proves nothing of significance. It is the weight of probabilities that is important.

This is another key point. People worry about inflation, but it is important to weigh the probabilities. Many smart people do think inflation is inevitable (as I do too), but we don’t really know when and how much. Some feel hyperinflation is inevitable and others have more moderate views.

But nothing is certain. When a scenario is certain and absolute (and many agree), you should look elsewhere anyway as you can only make money on the divergence between perception and reality. (There is a conundrum here as gold and other hard asset prices says inflation is inevitable but bond prices say deflation).

Stocks Outperform Inflation Over Time

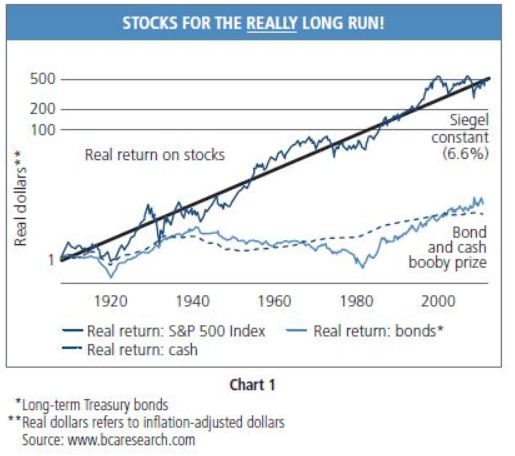

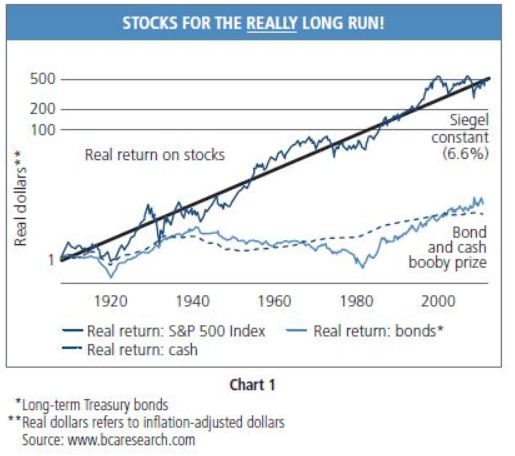

OK, so I’m going to borrow this chart from Bill Gross’ (PIMCO bond guru) recent, controversial letter that I will comment on later.

This shows that stocks over time have handily outperformed inflation, bonds and cash. But the key words are “over time”. Of course, stocks were flat in the inflationary 1970s. One might have averted that flat period by successfully timing the market, but I think it’s been proven that nobody can time in and out of markets over time successfully (most individual investors lose money or underperform because they get in and out of stocks at the wrong time!).

(I have shown here that there is a class of investors (residents of a village) that can make good returns in a flat market period without resorting to getting in and out of the market. This group has outperformed in all sorts of market environments over long periods of time. I have yet to find similiar performance figures for tactical asset allocators and market timers).

Fear of 7x p/e Stock Market

So anyway, yes, if inflation spikes up like in the 1970s, stock prices will go down and may go down really hard. But we don’t know when and how much things will go down. One big risk in avoing stocks until such event occurs is that it may not happen as planned. Back in 1987, people thought a 1930s-like depression was inevitable (so they stayed out of stocks). Others thought that the market won’t bottom until the market p/e gets to 7x. They looked at a long term chart of market p/e ratios and they saw that the market went down to that level in 1932 and 1972. So they figured it must get there in 1987 or 1988 too. In fact, many called for 7x market p/e’s in 1990-1992 too during the Iraq crisis, real estate / Citibank crisis etc. I heard people call for it in 1997/1998 too.

If there were two times it should have happened, it was after the 2000 bubble collapse and of course the financial crisis. The market p/e didn’t get low then either. You can fairly argue that stocks haven’t done much since 2000 so it doesn’t matter; staying out of the market wouldn’t have cost much.

But it’s still not a certainly that we will get 7x p/e’s in the near future.

So what if it does? Odds are that people who get out now and wait for a 7x p/e before jumping back in will do worse over time than people who ride it all the way through.

Cheap Can Be Good for Current Stockholders

There is a big difference between thinking that the bear market will bottom at 5x or 7x p/e and thinking that stocks will get to 7x p/e and stay at that valuation forever. If you think the former, it doesn’t matter. If you think the latter, then maybe you are better off staying out of the stock market (even though you have to calculate the odds that you may be right etc.).

People want to keep cash on the sidelines so that they can buy stocks when they get cheaper, or so they can moderate the losses on the downside.

This is something each person has to figure out on their own and do what is comfortable for them. But it’s important to remember that even if you are fully invested, that doesn’t mean you can’t take advantage of a cheap market.

Charlie Munger talked about this at a recent annual meeting. He said low stock prices is good because it allows good companies to grow. He said this is how Rockefeller, Carnegie and others got rich. They were around in bad times to buy stuff on the cheap to get bigger. Without the bad times, they wouldn’t have grown as big and wouldn’t have gotten as rich (I assume Munger meant Rockefeller/Carnegie got big at the company level; strong balance sheet and good cash flow to reinvest in bad times to expand).

If you own a stock that generates good cash flows, then you are going to benefit in bad times as long as the people who run the business know how to allocate capital. They will get better deals than most individuals and even most professional investors will get.

This is why it’s important to invest in companies with solid businesses with high moats, not too cyclical and strong balance sheets.

Most investors are afraid of the mark-to-market losses they will have to take on a decline in the stock market and they don’t think about what happens on an upturn after that.

So even if you have no cash and are fully invested, that doesn’t mean good companies you own can’t take advantage; in one sense, you are not fully invested. (Think about the companies that I write a lot about here; BRK, LUK, L etc. A lot of these companies have good cash flows and excess capital they are waiting to deploy. This is true for strong operating companies too).

Culture of Equity is Dead

So Bill Gross wrote a letter stating that stocks are basically dead and even said that the stock market is a sort of Ponzi scheme. He points to the difference in real stock market returns over time of 6.6%/year versus a real GDP growth over time 3.5%/year and says it is unsustainable as the stock market is just skimming 3%/year off the top. Many have already pointed out the error in Gross’ thinking; that difference is basically dividends that get paid out.

He confused growth in stock market capitalization and total return.

In any case, there was something else I thought about while reading that letter. Even if the stock market as a whole can’t outdo GDP over time, I do think that great companies can (not that we can always identify great companies).

For example, Walmart has been taking market share from unlisted, small mom and pop shops for decades. This would show up in an increase in stock market earnings over and above GDP growth. The same could be said of some great restaurant companies. Roll up strategies might give the same effect. Globalization can also contribute to this trend; McDonalds, YUM Brands, Coke all get a lot of growth outside the U.S. and yet book earnings here in the U.S.

As usual, regardless of what the macro, top down charts show, at the end of the day, it’s all about the individual businesses and the price you pay for them.

P.S. Market Up More Than 11% YTD

Not that short term stock market movements matter much, but I just couldn’t resist pointing out yet again the futility of macro-analysis for stock market investing. All year, we have been worried about a real implosion in Europe and even China. I too was convinced that a real crash may happen and things really might get out of hand. Reading the newspapers every day was a scary thing to do; sometimes I just wanted to not read the paper at all.

And yet here we are with the S&P 500 index up over 11% on the year. As I said many times before, if you took all that has happened this year, went into a time machine to the beginning of the year and told them what would happen, I don’t think people would have guessed the stock market would be up at this point. (On top of the Europe problem, slowing China and the fiscal cliff, we also had JPM’s whale problem etc.)

Louis Bacon recently gave back some of his investor’s capital saying the markets are too tough to trade with all of this macro noise (or more the government interference). He is supposed to make money off of that. He complained that political meddling / interfering in the markets has made it hard to make money. I scratched my head because it seems that that has always been the case. Remember the Greenspan put? Remember the Plaza accord? Central bank intervention in foreign currency markets? Rubin’s bailing out of Mexico? LTCM bailout?

I think it has always been pretty hard. I would guess that Bacon’s problem is size, and possibly even information flow. I think some hedge funds were privy to some good, advantageous information (not necessarily illegal inside information) in the past and due to the crackdown on banks, independent research firms, insider trading busts and overall heavier regulatory scrutiny, maybe that sort of information doesn’t flow as much as it used to. But that’s just a shot in the dark guess. (I noticed that a high performance hedge fund’s return started to slow dramatically also around the time that independent equity research companies started to be investigated. This may be a coincidence, but I always wondered about that. Still, size is probably the biggest hurdle to high performance).

For equity oriented hedge funds, Sarbox and Reg FD may be a factor too in flattening the information flow; previously analysts were able to get access to more information and pass that on to favored institutional investors including hedge funds. These new regulations made it harder to get good information.

This is nothing new; I am not making any allegations. Michael Steinhardt himself has said in one of the Money Masters books that one advantage he had was that he paid Wall Street so much in commissions that he was a valued client. Therefore, he often got the first call on upgrades, downgrades etc. And when he didn’t get the first call, he would go ballistic.

The world has changed quite a bit since then, and this may be a factor in the moderation of hedge fund returns lately.

i really think you should start this post with the Hard Assets or Stocks?

and finish it with the Book part. get us str8 to the good stuff.

great post tho!

Thanks for the comment. Yeah, maybe that would have been better. My posts do sort of end up as stream of thought kind of thing; I wasn't sure where I was going. I don't want to change it after posting, though (except fixing typos and minor changes).

The way I think about inflation and other items is that it affects everyone. Thinking in only relative terms and not absolute terms, inflation is something that affects everyone, and so prices will adjust. In some though, price changes may take more time than in others, and some companies may stay ahead of the inflation instead of responding to it – if you have pricing power, you can adjust pricing very quickly, whereas others may be lagged. Inflation in and of itself isn't an issue as much as unexpected inflation is specifically for insurers.

Regarding stocks for the "really long term" – it's interesting to note the different mentality among some investors. Some want prices to go up, but when I invest in a rock solid company, I would prefer the stock price to go down and stay that way for years. Good operators will get a chance to retire shares at a very low price and it will provide more time for me to accumulate the stock. With a 20-30 year time horizon, I think this will out perform those chasing instant gratification.

The challenge with investing, in my opinion, is the feedback loop. The markets let us think that their movements are our feedback loop, but I don't buy that – our feedback loops are really long. If you write a set of 1,000 auto loans that are set to be repaid in 2 years, then you know how you did on an absolute basis in 2 years, or whenever everyone has paid off their loans.

In a business though, that feedback loop can be 10, 20, or even 30 years. Even if a stock price rises over 1 year and you exit with a big success, is that something to celebrate? I think we need to continue monitoring the performance of the company to see what happens, otherwise if it's going to blow up, then it's an adult version of hot potato.

This 10+ year feedback loop also means that investors only have a certain number of opportunities in which to run their "experiments," because our lifetimes do not allow for 100's of tests to be run. If you assume that someone starts investing shortly after college, at 25, and do it till they are 75, then you're at 50 years of total time. In that period, your 10-year feedback loops mean that you'll only experience 5 iterations in sequential order. There are other ways of viewing this to argue that there are 50 iterations, however the point is still that there is a really long *real* feedback loop versus the *artificial* one of the stock market.

(I know there are also arguments for the way the stock market operates, because there is an element of probability embedded in it, so your thought process could be right despite the stock falling, and I will grant you that this is a good argument. The challenge I see is that 1) I don't think any investor can distinguish between 76% odds of something succeeding and 78% of the same thing happening, and even then, the results can be so widely distributed that it's tough to quantify, and 2) It lends us to a shorter time frame in which we are focusing on what others are telling us rather than what we believe to be correct)

Great post! Had the same feeling about the research boutiques and hedge fund returns – peculiar coincidence.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Your post is really good providing good information.. I liked it and enjoyed reading it. Keep sharing such important posts.

A nice article with a great stuff of information, I really like that. This is really interesting site that gives huge of information to all readers thanks a lot.

Structured finance

Very nice and helpful information has been given in this article. I like the way you explain the things. Keep posting. Thanks..Stock Tips

How does inflation affect the stock market? How does it affect your stock investments? Some companies compensate for inflation by raising prices. However, globally competitive companies are unable to stay competitive against foreign producers who don’t have to raise their prices to fight inflation. Also, inflation robs companies of the value of their increased prices. This means they are paying more for less, and this forces them to overstate their actual income, when in fact, the raised prices have no real value at all.

Neil Salser

Hi,

Thanks for posting. I did make a post about inflation and the stock market. Check it out here:

http://brooklyninvestor.blogspot.com/2012/03/on-gold-and-inflation.html

Buffett also wrote an essay about how inflation swindles the stock investor back in the 1970s. He explained how inflation is not good for stock investors, but ended the article by saying that he was buying stocks.

Over time, if you have a good business model, you are going to be able to earn what you deserve. If you do add value and provide a product or service people want, you will be able to earn a fair return on your time, capital etc…

Inflation has been positive in just about every single year in the past century and stocks did very well. A Coke cost, what, $0.01 per serving? $0.05 per serving? And now it's more like $1.00. Coke investors did just fine.

Of course, it would have taken a genius to find Coke back then to invest and hold through everything, but even if you just stuck with stocks in general you would've done fine.

High inflation like the 1970s will depress stock prices due to the impact on earnings and higher capitalization rate caused by higher interest rates, but when it inevitably settles down, the economy will reprice and the good businesses will earn decent profits again. The trick is to be able to have confidence and hold on until you get to the other side. Many don't (and that's why there are so few Buffett-like billionaires).

Hi kk,

This is a brilliant writeup. If you haven't link it recently, I could have missed it.

BTW, there is a dilemma that has been puzzleing me for some time. Some great businesses are great because they can increase prices above inflation. Eg. Coke, Sees Candy. But surely that can't continue indefinitely, right? At some point coke price has to grow in line with inflation. Otherwise a can of coke will become too expensive relative to other goods. If you have a meal, its OK the main dish cost $10 and the drink $2. But its not if the main is $10 and the drink is also $10. You would rather to have a full stomach than satisfy your crave. Thoughts?

Hi,

Thanks. That's a good point; things can't keep going up above inflation every year. That's what happened to healthcare cost and it hit a ceiling recently.

I think the point with these companies that have pricing power is that they have pricing power enough to offset cost. Their margins don't necesarily keep rising for 100 years, right? And if prices don't grow above inflation, they should be able to manage cost to maintain margin etc…

So that's the way I would think about it.

Thanks for reading.

Thanks for posting this informative post. I like the content because its rather easy to understand. And the topic captures my attention. Keep on posting like this and more power

Very nice and helpful information has been given in this article. I like the way you explain the things. Keep posting. Thanks.. Stock tips

This article is full of excellent informative content. The points you make are interesting and original, and I agree on many of them. Thank you for writing on this topic.

offshore banking

This page is very informative and fun to read. I appreciated what you have done here. I enjoyed every little bit part of it. I am always searching for informative information like this. Thanks for sharing with us.

This is a really good read for me. Must agree that you are one of the coolest blogger I ever saw. Thanks for posting this useful information. This was just what I was on looking for. I’ll come back to this blog for sure!