I haven’t posted in a while but that’s because I was busy with all the conference calls, annual reports, and of course, keeping up with all the stuff coming out of the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting.

Anyway, there is plenty of stuff out there on the annual meeting and I don’t have much to say about it; it seems like the usual, same old stuff. It was great that Buffett invited a short to ask questions. People have often complained about the softball questions that Buffett has gotten, and the often non-Berkshire-related questions over the years. So he got journalists to sort out questions ahead of time and then invited professional securities analysts to ask questions that might satisfy the more hard core Berk-heads. That was a good idea. And to make it even more interesting and have tougher questions asked, he invited a short this year. Unfortunately, I don’t think any of the questions the short asked were very interesting and I could’ve answered those questions exactly as Buffett did (this is what happens when you follow Buffett for years; you tend to know what he is going to say before he says it).

OK, this is not the topic of this post. Let’s get back on topic.

Stock Market Overvalued Due to High Margins?

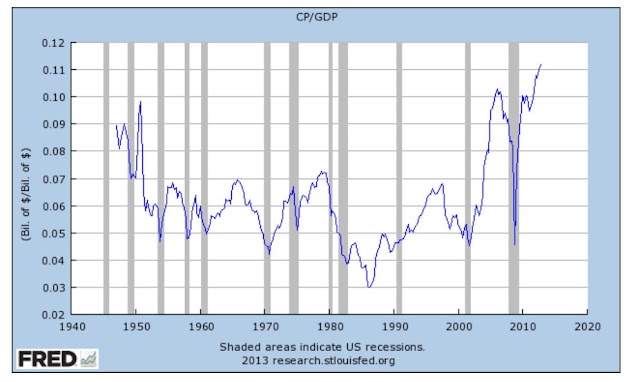

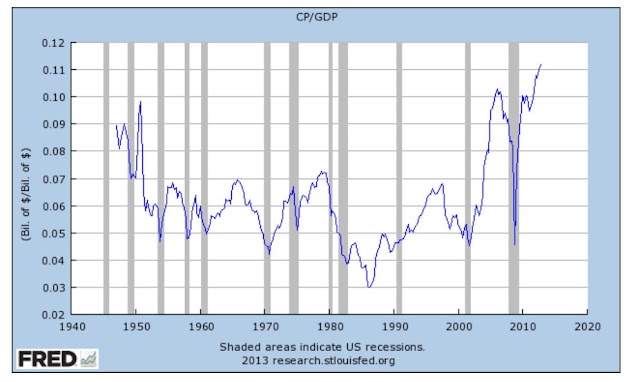

People have been saying for the past few years that the stock market is overvalued despite reasonable looking p/e ratios because earnings are abnormally high now. The usual chart shown is the corporate profits-to-GDP ratio. This has been trending up and it is unsustainable. Even Buffett said a while ago that to think corporate profits can stay above 6% of GDP is fantasy (it is now over 11% according to the chart below from the St. Louis Fed). Someone asked this question at the annual meeting and Munger said that just because Buffett said something a long time ago doesn’t make it carved in stone (or something like that), and he added that he thinks 6% is a little low.

Despite this record high corporate profit-to-GDP ratio showing abnormally high margins at U.S. corporations, Buffett said that the stock market is reasonably valued. Howard Marks said that too in one of his recent memos. Are they blind? Don’t they see that current earnings are bloated and unsustainable?

I looked at this a while back and concluded that none of the big blue chips companies have this trend in profit margin (corporate profits-to-GDP is not the same as profit margin but is used as a macro proxy…); I made a post about this a while ago (see here).

So I comforted myself by saying that if there is a stock I own that is showing rising and unsustainably high profit margins, I should watch out and lighten up. Having not seen that in my companies, I didn’t care. In fact, since I was mostly interested in financials, most of them showed below trend profit margins. This big chart of profit margins was not relevant to me at all.

I still don’t care too much about it as I don’t look at stocks as part of a stock market, but more as a piece of a business (would you sell the restaurant you love and built over the years just because the S&P 500 index is trading at, say, 50x p/e? Nope. If someone offered you 50x p/e for the restaurant itself, then you would have to think about it, of course!). If I like the business, how it’s doing and it’s current valuation is reasonable, who cares what some GDP ratio shows?

Having said that, I was still curious how people can keep saying (including myself) that the stock market is reasonably valued despite this fact.

Actually, the question is more why people like Buffett are not more worried about the market (we know he ignores market predictions but still) with this crazy looking chart. Why does he keep buying Wells Fargo every month (well, I told you he will keep buying WFC all the way up to $50/share. see Wells Fargo is Cheap!)?

Anyway, let’s get to the picture:

There are a lot of these charts all over the internet; people have been talking about this for a long time now. I’ll use the St. Louis Fed’s chart since they probably won’t come after me for copyright issues.

The chart is certainly staggering. I too tend to get acrophobic when I see charts like this with something shooting way out of range. Corporate profits has been in the range of 4-6% or maybe 5-7% for a very long time but is now above 11%. This can’t continue. The argument is that if profits went back to 5-6% instead of 11%, then the stock market p/e ratio of 15x (or whatever it is currently) would actually be 30x on a ‘normalized’ basis.

Scary for sure. I do agree with the fact that these things do tend to mean-revert, and I also realize that there may be factors (international business of U.S. corporations) that might make this trend up over time.

But I don’t want to get into the details of that now. The point of this post is much simpler.

What Are We To Do?!

The question is, with this ratio at such abnormally high levels, what the heck are we investors supposed to do? “Experts” tell us to get out of stocks or lighten up as profit margins are unsustainable and the market is expensive on an ‘adjusted’ basis.

As I said before, my personal reaction is to do nothing and just look at my holdings and see if I have a problem with any of them. If I owned a company that typically earned 10% operating margins and that went up to 20% due to some supply constraint that made the product prices spike up and input costs were lower than usual and the stock price reacted and is priced as if 20% margins is ‘normal’, then I might lighten up or sell out completely. If that is not the case, I would hold on. Who cares what the ‘national’ level profit margins are?

If you owned Berkshire Hathaway in August 1987 and were convinced that the market would crash soon, would you sell out? How many times would you have sold due to various reasons over the past few decades? And out of those times you would have sold, would you have gotten back in?

Anyway, let’s get back to the above chart. Profit margins seemed high back in the late 40s and into 1950. Interest rates were probably below 2.5% back then, and profit margins were pretty high. If you knew for a fact that the corporate profits-to-GDP ratio is going to head down, would it have made sense to stay out of the market and wait for it to get to a level that is more comforting?

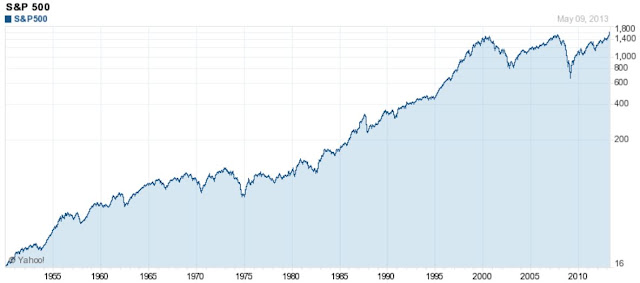

Here is the S&P 500 index from 1950 or so onwards:

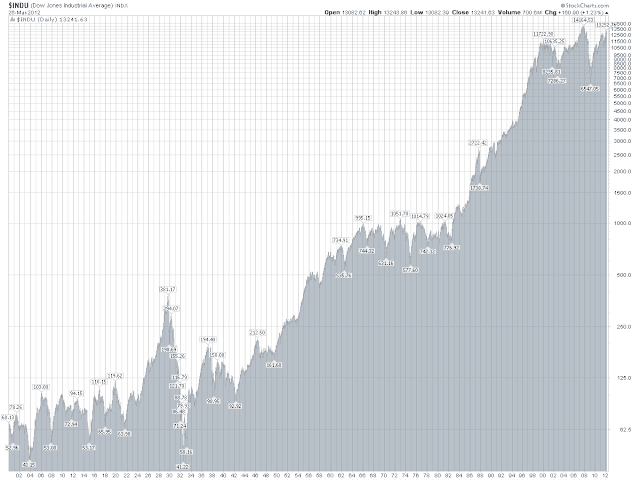

…and just for fun here’s the Dow in the last century:

So, check this out; from 1950 on, corporate profits as a percentage of GDP headed straight down all the way until it bottomed out in the mid-1980s. You can draw dots in February 1950, 1955, 1960, 1970, 1980 and 1985 and except for 1980, the ratio is lower than it was the dot before. I am eye-balling this so I may be off a little here and there. But the basic message is the same. Corporate profits-to-GDP went down all throughout that period.

OK, so here’s the fun part. You saw the S&P 500 and Dow charts so you already know where I’m going with this. Let’s see what happened to the stock market since February 1950. I used February since that was the earliest datapoint on Yahoo Finance for the S&P 500 index. I do have complete data somewhere, but I didn’t bother to look for it as I think this is good enough.

Let’s look at what happened from February 1950 onwards to the S&P 500 index:

S&P 500 annualized

level return since 1950

February 1950 17.22

February 1955 36.76 +16.4%

February 1960 55.49 +12.4%

February 1970 89.50 +8.6%

February 1980 113.66 +6.5%

February 1985 182.19 +7.0%

Keep in mind these returns exclude dividends. It’s only the change in the index.

So if you somehow had perfect foresight and you knew that the profits-to-GDP would head down in future years (back in 1950) and waited, when would you have bought stocks? If you waited until it bottomed out in 1985 (actually, I think it bottomed a little later, but…), you would have had to pay 11x as much as you could have paid for stocks in 1950.

If you waited five years, you would have missed out on +16.4%/year in returns. If you waited a decade, you would have missed +12.4%/year in returns etc.

So even if you knew for certain that profits-to-GDP would head down in the future, you still would have had no idea what the stock market will do. This is the essence (or one of many) of Buffett’s approach to these macro things; even if you knew exactly what the unemployment number would be one year from now and what the GDP would be, you would still have no idea where the stock market would be. There are just too many unpredictables, or what he calls unknowables.

Please excuse my very rough eye-balling, but let’s look at what happened during the time that profits- to-GDP went down versus the time it went up. As we saw in the above table, in the 35 years between 1950 and 1985, the ratio went down a lot, but stock prices rose 7%/year. Since 1985 through February of this year when profits-to-GDP went straight up to the current, obscene, unsustainable level, (just to keep the Feb-to-Feb comp constant), the S&P 500 index went up 7.9%/year.

So the market went up during the years when profits-to-GDP went down, and the market went up when this ratio went up. Is the profits-to-GDP really such a good indicator for stock market timing?

You can also try plotting the highs and lows of the profit-to-GDP chart and match it to the stock market. Maybe you would have gotten out in 2006 or 2007 and then gotten back in in 2009. But then maybe you sold out in 2010 or 2011. Not bad. But then, over time, you might have bought in 1970 and then sold in 1978 only to get back in in 1985 or 1986. You get my point.

Buffett has this sort of long term perspective on things and that’s why he is not alarmed or overly concerned with these things. It’s not always easy to do, but sometimes you have to look at the whole picture, not just the big picture. People, myself included, sometimes get mesmerized by certain graphs and charts and make them overly weight it and distract us from making good, rational decisions.

Interest Rates

We can make a similar argument about interest rates too. People say correctly that the stock market had a massive wind at its back with interest rates going down from double digits in 1980-82 all the way until today. They say that this wind at its back is now a headwind. Combine that with the abnormally high profits-to-GDP and the stock market is dead money, at least, for a very long time.

But again, in 1950, interest rates were 2% or whatever. That went up to double digits. I think rates peaked out in 1982, but since we already did the work for 1980, let’s look at that. The S&P 500 index went up by 6.5%/year from 1950 to 1980 despite interest rates going from 2% to 10% or so. And that 6.5%/year includes the stock market being flat pretty much since 1965 through 1980. And remember, these stock market return figures exclude dividends.

Conclusion

So here we are today with interest rates at unsustainably low levels and profits-to-GDP at unsustainably high levels. Putting those two together, it’s hard to imagine the stock market moving higher. At best, it seems like it will be flat for a long time to come.

But looking at the whole picture and not just at cherry-picked charts here and there that look scary, we see why Buffett says that the market will keep going up and will be substantially higher over the next few years even though he admits he has no idea what the market will do next week, next month or next year.

I am not arguing that stocks will go straight up and will always do so. I look at these charts and do believe in mean reversion and all that, and I don’t entirely disagree with the bears out there. But I just like to take one step further and ask myself, well, what would have happened if I used this as an indicator to get in and out of the market? Would I do better than just holding on to great businesses or buying special situations? A little digging shows that maybe not.

I don’t think these charts are irrelevant either. It’s just that there are so many factors that are not knowable that we can’t really predict what is going to happen based on one or two (or even five to ten) really, really convincing charts.

The S&P 500 was at a P/E of 7 or 8 in 1950.

I agree with you mostly. 🙂 But here are some devil advocate thoughts: perhaps market was very cheap in 1940's. If market was trading at 4 PE and margins dropped 50%, the PE would go to 8 PE, which is still very cheap, so market could go up (to PE 10-12) while margins dropped.

Another possibility is that GDP growth was high, so the drop of "margins" (not really margins, rather profits/GDP ratio) was due to high growth and therefore again market did not have to drop as ratio dropped.

Neither of these possibilities apply to current situation. 🙂 Well, perhaps GDP growth could jump up…

Good point. I think the first response is correct; p/e was around 7-8x in 1950 so much of the gains after that was p/e expansion.

But we can look at the 1950-1980 figure and that neutralizes the p/e part of it as the p/e in 1980 was also in the 7-8x range. And yet, with interest rates rising substantially and margins declining, the stock market did pretty well from 1950-1980 (see table in post).

And yes, that's thanks to the high GDP growth we had during that period which is unlikely in the future for us going forward.

But my point would be that we really don't know what happens going forward. Maybe U.S. corporations make more and more money internationally so earnings are not anchored to U.S. GDP as much as in the past.

I actually have no idea, and that's sort of the point.

In any case, I don't invest this way and spend much time on this sort of thing so I am not leaning on any of this stuff I say for my own investment performance.

And yes, I do see that we can't expect the high returns we've had in the past going forward. But that doesn't mean stocks is not the place to be…

Thanks for posting.

Back foreign profits out and see how things look. I have done some analysis on this if you want to see it. Need your email address though Brooklyn.

Hi,

Thanks for the offer. Can you post a link to a google doc or something so others can see too? I haven't publicized my email (although I will email people who put their emails here first).

Thanks for reading and posting.

Thanks so much for all your posts. I really enjoy them and feel like I learn a ton. Sorry to be off topic, but I would love to hear your thoughts on Banco Santander. Either way, thanks and have a great weekend.

Hi,

I do post a lot about financials, but I actually don't follow a whole lot of them. I write confidently about JPM, WFC etc. because I have been following them for years. So when I say JPM is a great buy at tangible book, there is a lot more behind that than just the simple valuation metric.

Unfortunately, I can't say the same for many banks around the world that I know are trading very cheaply, particularly European banks. I just don't have that familiarity with them, their cultures, management, experience as customer and knowing people who work or have worked there etc… (which is the case for U.S. banks/investment banks I talk about a lot).

Thanks for reading.

Your talking of getting out of the market. Where exactly were you thinking of running? Into Dollars, going completely liquid? Cash is an investment just like any other, and with FED intent on ruining its value, not a very promesing either.

Well, if the market was trading at silly levels including stocks I own, then I would not hesitate at all to go to all cash despite the risk of owning cash.

So the "what else is there?" argument works for me to a point, but only to a point where stock prices are reasonable. At times, cash can be the least worst option, but I don't think we are at that point.

Thank you very much for all these posts!

Excellent post, fresh and thoughtful, as usual on your blog. I always look forward to new posts from you. Thanks!

Hi, without looking at any numbers in detail my guess would be that the high earning to gdp ratio must be due to the advent of new high margin industries in the last 10 years.

Software/technology companies would be my primary suspect

As an example Apple with roughly 4% of the total s&p 500 earnings and 30% profit margins or Microsoft with roughly 20 billion of net earning power on less than 80 billion turnover.

These companies are becoming bigger and bigger in the last decade and so have a big impact on the ratio.

There are lots of this type of companies that simply didn't exist 20 years ago and have become enormous in the last 10 years.

Of course there is the other reason that is in everybody's head, companies are not seeing an increase on the top line so they are increasing their bottom line through cost cuts (increasing their profit margins) but given the scale of the increase on the ratio and the advent of the technology giants in the last decade i think that the first reason is the most important one.

About the interest rate environment my thoughts are:

1. The yield decrease in the last 30 years has helped companies as they can finance themselves cheap and increase their margins and leverage (sometimes this is also dangerous in companies with reckless managers)

2. Low rate environments rise the valuation of other assets as the treasuries are the yardstick used to measure any asset.

3. Contrary to conventional wisdom (please correct me if i am wrong) I think that and environment with interest rate rises is good for stocks. The reason for this is that when interest rates are going lower money flows into bonds because the price of them is going to increase over time and because today's yield is going to be better than tomorrow's and the opposite in a raising interest rate environment (bonds are going to lose value and I have an incentive to wait as i would get a better deal in a few months time). So in a raising interest rates environment more money flow into stocks (normally this raises happen with economies that are gathering momentum also)

Thank for your blog I think it is one of the best out there.

Hi,

Thanks for the comment. Yes, there are a lot of reasons for higher profits to GDP these days, one of the big ones being foreign profits of U.S. corporations. Lower labor cost, taxes and interest expense are other factors too. Having said all I said, it's not such a great idea to assume this will keep trending up or that it won't go down. It will eventually, at least a little.

As for interest rates, there is no question that we had a massive wind at our back, at least since 1982. Interest rates went from double digits to under 2%, so that does a few things. One of them was that stocks were at 7x p/e back then and now it's a more normal level and lower interest rates is part of that. Lower interest rate leads to lower discount rate and therefore higher asset prices. Also, borrowing gets cheaper and a lot of debt has been used to create the great demand we have seen in recent years. Plus interest expense at corporations go down so profits go up.

So to think that the reversal of this would be good is probably not correct. I would say that a rise in interest rates would hopefully reflect an improving economy, higher demand, and things like that. If that is the case, that interest rates rise in a normal way and not spike up, then it might not be as negative as it should be, and the positive aspects of higher inflation (pricing power at corporations, rising yields/income for banks and insurance companies etc.) and stronger demand/improving economy can offset that.

That's more the way I would look at it. And as for cash flows, yes, I suppose cash may flow out of bonds into stocks, but that wouldn't be the first reaction if interest rates start to go up (they may rush into cash first and avoid stocks as the market might think higher rates is bad for stocks).

One good thing, at least from the valuation standpoint, is that p/e ratios hasn't kept up with interest rate declines. Not too long ago, the FED model for the stock market was to look at the earnings yield against the 10-year treasury rate. That worked for a little while in the 1980s and 1990s, but hasn't really worked over longer periods of time.

But using that model, the stock market would be trading at an earnings yield of 2%, or 50x p/e. That's nonsense, and thankfully the market hasn't taken the market up there (yet. Who knows, maybe it will get there).

If the market was at 50x p/e, then a rise in rates would certainly kill the market.

The earnings yield stopped declining at a certain point even as interest rates continued to decline. So from a purely valuation standpoint (and ignoring what interest rates will do to the economy and earnings), there is a lot of cushion for rates to rise before it hits the p/e ratio.

Anyway, who really knows. But it's fun to talk about sometimes…

Thanks you for the reply.

I completely agree with the thesis of your post, the margins are not unsustainable in the sectors where you are invested so there is no need to worry about investing in particular stocks particularly if you believe in the bottom up approach that the best value investors apply.

My approach is similar and i am a long term buy and hold investor but i find very interesting looking at the macro picture.

Going back to interest rates my thinking is based on the last couple of cycles in the last 10 years. If you look at a graph of the S&p 500 and the fed rate when the fed starts easing (2001 and 2007) I see an initial spike on the indexes that lasts a few weeks or so followed by the market tanking.

The 3rd of January 2001 the fed cut rates and the s&p 500 bounced from 1283 to 1347 in the day and eventually went to a high of 1375 by the end of the month; from there the market went to a minimum of of 775-800 between the autumn of 2002 and early 2003.

In 2007 something very similar happened the s&p lost 100 points in a week in mid august and the fed reacted by cutting rates. The market bounced again going from 1400 to 1560 by mid October and from there to the 2009 lows.

The reaction when rates start raising is similar but not as clear cut but also points in the same direction. In late June 2004 the fed started raising interest rates, the s&p 500 went from 1140 the day of the announcement to 1060 mid august and from there it kept going up all the way to the 2007 highs.

This time interest rates have been kept extremely low for a very long time plus the QE which put us into uncharted territory so if you would have waited for the interest rates to start rising you would have missed the whole upswing but i still think that the reaction would be the same a steep drop that could last 4 to 10 weeks followed by a bull market.

I think that the steep decline is a sure thing but i would see it as an opportunity to buy.

This i think is specially relevant for financial shares as the decline will be the steepest but in reality the interest rate raises are fundamentally good for them as they will make a lot more money with higher interest rates..

This is not so good for other sectors as the consumer would have less money in their pocket as the rates raise.

My 2 biggest positions are BRK and MKL but i like the banks at this prices. What put me off buying them are the high taxes on dividends that i would have to pay in the country where i am resident. I specifically look for companies that pay no dividend

I think that this scenario is only applicable to interest rate hikes that come as a consequence of economic recovery. If the interest rates are going higher in a bad economy to control inflation like in the 70s this would not apply.

I also think that valuations are fair at the moment there is definitely no bubble in stocks but they are not cheap either and it is difficult to find good values except in the financial sector.

Hi K, thanks for writing what is one of the most insightful finance blogs out there. Your title on Buffett made me refer back to your posts on WFC being cheap and I was wondering if I could ask a brief question – I've been looking into Banco Santander de Chile (BSAC) and it seems to be priced at 3x equity. Can this ever be justified?

Hi,

I am not familiar enough with the bank to say. High valuations can persist for a long time so it's hard to say. If the bank is earning high ROE's without excess leverage and is managed conservatively, it may be maintained, even though history shows that high valuations tend not to persist forever (U.S. banks/investment banks were valued highly too for a long time until the crisis).

Also, accounting may be an issue. In some countries, balance sheets may not be marked to market. U.S. financials too used to mark their books at lower of cost or market; in this case, stated book may be way too low. There are other reasons why that may be the case.

So you would really have to dig in to see why the bank is trading at 3x book, and I don't know enough about it to say…

Thanks for reading.

I agree with some of the early posters – stocks can do well if interest rates are rising and profit margins are falling IF you purchase them at low valuations. That is certainly not the case for the broader market today with a Shiller PE of 24.5. High initial valuations = low long term returns, an investor who correctly guesses that stocks will become even more overvalued can do well, but in doing so they are risking capital losses should Mr. Market price stocks in line with historical norms.

Hi kk – Not really sure why the "rest of world" corporate profits in the fed flow of funds report is normally excluded from the corp profits to gdp ratio. maybe there's a good reason, but it is available and according to the FoF definition does support that more profits are earned internationally. i'm probably oversimplifying (not an economist) since it seems too easy of an adjustment. Plus, as you mention, it shouldn't drive investments anyway…

posted to google docs if any readers know why this isn't usually incorporated into the profit margin proxy ratio.

rest of world portion of profits to gdp is 2.7 pct points for 4Q2012, which if incorporated would equal 8.4% profits to GDP, not that far from mean. also some benefit from lower taxes using the same FoF data.

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B5l5PcmIV1nGTGRnTjFMeXdpU3M/edit?usp=sharing

https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B5l5PcmIV1nGRVhRUG8wOVFLSTg/edit?usp=sharing

I realize not everything Buffett said a long time ago is written in stone, but he did once comment that Total stock market cap/US GNP (which approximates GDP closely) is "probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment." Right now the ratio is at a historically high 112%. Buffett has said he likes to buy when the percentage is much lower…I forget exactly what the quote was, but I think he said he prefers something like 80%, obviously the lower the better. This info, compared with the CAPE being around 25, makes this seem like a pretty damn expensive market. Jeremy Grantham certainly agrees and claims the S and P's fair value is a shocking 1100! (though Im starting to think he is sort of a perma-bear). Any thoughts you have on these issues would be greatly appreciated. This is my first time in a situation such as this.

That's a good question and I do think about it a lot. The quick answer is that if you are an investor that picks individual stocks, just focus on the stocks you own and see if they too are ridiculously overvalued. I think the correct way to look at this is on a stock by stock basis. The big, macro figures don't tell you everything. For example, the S&P was bubbled up and expensive in 2000, but BRK and other value stocks were not. It would have been a huge mistake to look at the S&P 500 index p/e ratio and then sell BRK or some other stocks that may be cheap or fairly valued.

So I don't think people should really look at this sort of thing too much for investment decision-making. So that's the answer that applies to individual stock-pickers.

What about folks invested in an index fund? That's a really good question. My take is that people usually don't improve on the performance of the stock market over time by getting in and out of it based on these things. The big charts keep telling us that the market is expensive or cheap in the past 100 years, but I have yet to see any sort of 'system' or a real investor that bought when the market was cheap and sold when it was expensive and did better than just owning the index over the entire 100 years.

Sure, there are folks like Druckenmiller that will trade the market a lot and make money buying cheap and shorting when it's expensive, but those macro guys spend all of their time thinking about these things plus they make a lot in FX and other macro trades. I wonder how they would do if they only traded in and out of the market. My guess is that their performance wouldn't be so good.

So on the one hand, here is Buffett telling us that most people don't do well in the stock market because they try to get in and out according to all sorts of indicators and reasons when he says that staying put is the best thing to do. And he is very rich with proof that his method works (OK, so he got out once in the late 1960s).

And on the other hand, you got guys running around with charts showing us that when the market got to this or that level, the market doesn't do well or whatever. And none of those guys can show me compelling proof that that means anything; in other words, how has that knowledge improved their returns over time? Show me someone who made billions by just getting in and out of the market like that, like a Buffett version of the idea. They don't exist.

I exclude macro traders as they act differently. Macro traders use futures and leverage to time market movements, so what they do is very different than what most retail investors and even conventional equity managers do.

Sure, you will find a few folks who did get out before the crisis and in during the crisis. But if you try to find someone who did that consistently over time, I think it would be very hard to find anyone.

So however appealing the idea is to sell stocks now and get out, you have to wonder if you will get back in at the right time (if ever), and if you can keep doing that over time in such a way that you actually beat the market.

Despite all the volatility and seeming opportunity over the years, studies still seem to suggest that invidual investors lose money more from getting in and out of the market than picking the wrong stocks.

If you are really worried and can't stomach a 50% decline, then of course, you should lighten up to a point where you can sleep well regardless. And this should be done no matter what the GDP ratio says, because the market will go down a lot every now and then, even when the market looks cheap.

Anyway, thanks for reading.

Thanks for the wisdom and for your time.

I've been thinking quite a bit about your posts on why the market doesn't seem bubbly despite record corporate profits to GDP, and I just ran into an article which might explain this seeming paradox:

http://seekingalpha.com/article/2111533-the-only-20-companies-that-matter

As you can see, US profits don't look too excessive when compared to global GDP. This is especially true when you consider pre-tax profits, which haven't been affected by declining US corporate tax rates.

Anyway, this is essentially just a quantitative way of expressing the fact that more profits are being earned by US companies abroad, but I personally do find it reassuring.

Hi, that is interesting.

Check out what Rich Pzena had to say about record profit margins recently:

http://brooklyninvestor.blogspot.com/2014/02/pzena-quarterly-newsletter-record.html

I have something special for you

today!

This Profiteering Software App usually

retails at $497 but for my subscribers

it’s FREE!

This is invite only: http://five-minute-profit-sites.net?CCM114