So, I keep hearing that markets are broken, or that the market is as expensive as ever. I know I keep saying this and I am sounding like a broken record, but I am not so sure. Well, let’s take one thing at a time. Are the markets really broken? Someone said this implying that value investing doesn’t work anymore as passive indexing has taken over and nobody is valuing individual stocks anymore. This may be true to some extent. If this is true, it may become even more so over time. One of the books I read early on was the Alchemy of Finance by George Soros.

I have not reread this one in a long time, so excuse me if I remember wrongly, but one of the takeaways I got from it was, Soros writes about how conventional economics gets things all wrong because they are based on the assumption that markets tend towards equilibrium when in fact that is not true at all. In fact, economies and markets are driven by self-reinforcing moves leading to big, wild cycles. This was a very interesting idea to me.

Now, looking at the “value investing is dead” idea from this point of view, it sort of fits to look at value investing as sort of the “conventional” view of things; maybe we are in an extended period of a cycle where things are diverging more and more.

Maybe this whole indexing thing is a self-reinforcing cycle of the sort Soros talks about. The more active managers underperform, the more investors rush into index funds, and the more investors rush into index funds, the higher the index goes, and the more active investors underperform. I won’t do this, but when I was planning on writing this post, I was going to create sort of a long/short basket of passive asset managers (Blackrock, mainly) and active managers (BEN, TROW, AMG etc…) to show how the passive guys are getting all the assets and active ones losing them. Of course, this can’t go on forever, but like any big cycle, it is very hard to call the turn. It may take a big bear market to wash out all the passive investors first, and maybe when investing is no longer viewed as the right thing to do, the next cycle will start with active managers outperforming the indices (like Buffett in the 50s). Maybe putting on a pair trade like this is a good hedge against ‘broken’ markets!

But is the market really broken?

I think this argument came up in the past too, in the 2000’s and 2010’s. And I always scratched my head. I understand what people are saying. But if you look at individual stocks, markets are clearly differentiating between individual stocks. Look at Nvidia vs. Intel. If nobody was really evaluating them and the market was ignoring fundamentals, you would think both stocks would be performing similarly. But they are clearly not. People are clearly differentiating between winners and losers. It’s a separate question whether they are over-discounting their views. That’s a different discussion, and contrary to the view that passive investing is killing fundamental analysis.

Another example: JPM, the better bank, is trading at 2.4x book, versus C, which is a crappier one, selling at 0.8x book. You can’t complain that the market is broken just because you don’t agree with it. On the other hand, Buffett in the 50s loved the fact that institutional investors of the time completely ignored company analysis / valuation.

Market Valuation

I know, I know, I keep coming back to this. There was an article recently saying how the market is the most overvalued in a long time because the earnings yield has basically gone below the 10-year treasury rate, something that hasn’t happened since forever. I have long said that I am a believer here in the old Fed model, and an earnings yield sitting at or below the level of 10-year treasuries is not a problem for me at all. It feels pretty normal.

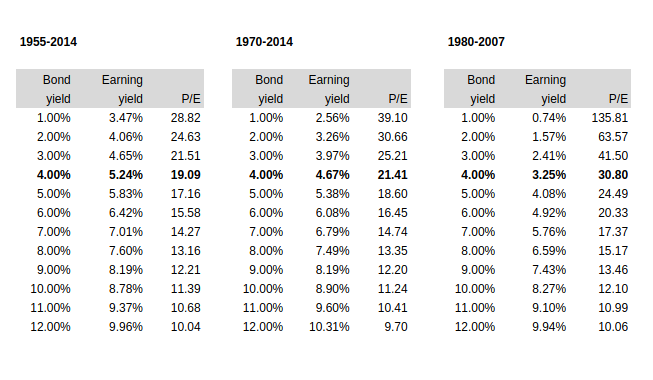

As I was looking for something, I came across these old tables I used for a post here a while back.

This is just a table of the results of a linear regression of earnings yields against the 10-year treasury yield. I think at the time, I thought a normalized long term interest rate would be around 4% (2% real growth, 2% inflation). As you can see, a P/E of 20x is not all that unusual, and not cause for a crash or anything like that at all. Using the various time periods, P/E’s can be normal at interest rates between 4% and 5%, at 17-19x, 19-21x, or even 24-31x if you look at the time period between 1980-2007. You may accuse me of cherry-picking time periods, but I just wanted to see how the relationships held in various time periods. I thought of updating this but I didn’t think it would give relevant information as interest rates went to zero on the short end, and QE made long term rates get below 1% after this period (2014, which means I probably posted this in 2015).

Crash!?

OK, so the above table is just for reference. Sort of a sanity check. This is not to say the market should be valued here or there. My point is, with this sort of history, the market can have a pretty wide “zone of reasonableness”, and what I’ve been seeing in recent years is not all that alarming.

Now, first of all, let me just say that a crash or bear market can happen at any moment, so I don’t mean to suggest we are not going to have one any time soon. These things can happen for any number of reasons. Especially now, when some say there are no adults in the room and the patients have taken over the asylum.

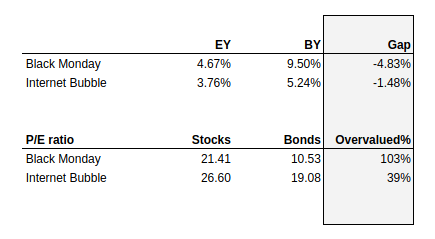

But, related to the above, let’s take a quick look at the two most prominent crashes. Black Monday and the internet bubble. Black Monday was before my time, but of course, like many others, I spent a lot of time reading about it, analyzing it and whatnot. But I told you the story about my early years in investment research. A colleague dropped a chart on my desk and it blew me away. It was an X-Y plot of the earnings yield vs. the 10-year treasury rate in 1987. It was like a perfectly straight line except for one dot that was way over the line, and that was August or September, 1987. I know I mentioned this here before, probably many times. But due to what I am reading in the press now, I think it’s important to point it out.

People are freaking out now that the earnings yield went below the 10-year treasury yield, but looking at the two big crashes of my generation, look at the numbers.

Before the crash in ’87, with P/E’s above 20x, the U.S. bond market crashed, and I think even spiked over 10% at one point. The above table shows that according to the silly, discredited (but still one of my favorite) Fed model, the market was overvalued by 100%! It needed to go down 50% to reach fair value. During the internet bubble, it wasn’t as bad, but the earnings yield went 1.5% below the bond yield, making the market 40% overvalued.

For me, that’s the “rubber band” I am looking at, and right now, it is certainly getting a bit stretched. With a P/E of 28x, currently, and the 10-year at 4.5%, the market seems 26% overvalued. Again, not to manipulate the numbers too much, but the forward P/E at the peak in 2000 was 25.2x, and long term rates were 6.2%, making the market 56% overvalued then. Now, the forward P/E is around 21-22x, and the bond P/E at 4.5% is 22x, so the market is actually pretty fairly valued on forward P/E.

The above regression table, it suggests that the earnings yield (ttm basis) can be fairly valued below the bond yield at certain interest rates (1980-2007 regression). That may be cherry picking (of the 3 tables), but 27 years is a long time period so not completely irrelevant. I think I chose that period because on an X-Y plot, it looked like there was a pretty visible, clear, straight line during that period. Before that was ‘extreme’ due to the high inflation of the 70s, and post-financial crisis was distorted due to QE QE2, QEx… etc. I know, this is not very academic, and it is easy to shoot down. Plus, who is to say we won’t have a period of high inflation again, or another financial crisis? So, excluding those periods may be unfair.

But for me, just looking at it and saying, during relatively normal times, what does the relationship look like? It gives me some perspective.

Valuation Sanity Check

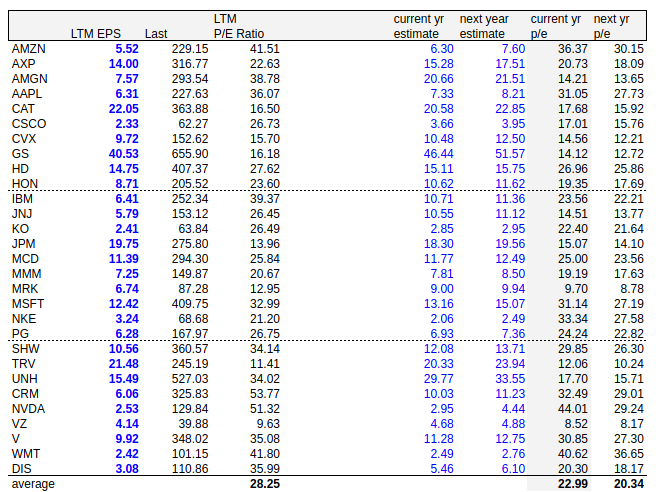

Here is another old table that I just updated by hand. I used to have a bot update this daily on an old web page somewhere, but things keep changing so I stopped trying to keep it up to date. Later, I will play with the Yahoo Finance API and see if I can create some data pages to keep up to date. But frankly, I am not all that much into data these days. I prefer just to read 10-K’s and listen to conference calls etc… But I guess having some data handy might be good. If I do anything, I will post it here. It is kind of fun to get a Jupyter notebook up and running and playing with data…

Here is the old table. I just updated it by hand now ( Just the blue stuff. Price is from Google Finance. I spent a lot of my early career updating spreadsheets by hand, so this is no big deal for me).

I excluded BA here as they are losing money, and since this is just a simple average of P/E ratio (and not an aggregate of total cap divided by total earnings, or total price / total eps), a negative P/E would understate P/E.

The LTM P/E looks on the high side, even for me, at over 28x, but current year and next year estimates are 20-23x, so not looking all that crazy. But that assumes the estimates will be achieved. If so, the market can consolidate here and let the earnings grow into the valuation. The S&P 500 P/E is also around 28x at the moment. Using the Fed model, the market looks 27% overvalued.

So, maybe for the first time, or maybe the first time in a while, I actually agree that the market is getting a little pricey. For the past few years, I pushed back hard against the idea. And, honestly, that was my plan when starting this post too. But facts are facts, the numbers are the numbers. The market is getting expensive. The market has had high P/E ratios, much higher than now in the recent past too, but I don’t care about P/E ratios during times of turmoil, like the financial crisis or during Covid shutdown. Just because it rains, or a hurricane is coming, you are not going to value your nice seaside restaurant by looking at the receipts on those bad weekends.

As mentioned above, though, on a forward P/E basis, things look OK.

When To Sell?

So, with the market looking a little expensive, what do we do? I have always said that I don’t really care too much about valuation if things get moderately overvalued. Even if things look a little bubbly, I wouldn’t care either. For me, what I want to avoid is a 10-year or 20-year bear market like Japan after 1989. And back then, P/E ratios went to 60-80x. It took Japan more than 30 years to recover.

During and after the internet bubble, if you held on, you would have been fine as long as you were not too exposed to the bubble stocks. So my view is still the same. I think a lot of funds did fine in the late 80s and into the 90s too, even with the crash. I wouldn’t want to get too clever and try to get out and back into the market based on valuations. We all know that usually doesn’t work, and it has destroyed the performance, if not careers, of a lot of managers. But, one good thing to do is to look over the portfolio and lighten up on things that are getting a little silly.

I do own COST, which is up to over 60x P/E, which seems a little nuts even to a valuation apologist like me for sure. WMT, I don’t own, is over 40x P/E too. Is this crazy? It’s one thing for good stocks to trade in the 20s and 30s P/E when the market was trading at 15x P/E. But with 20-22x P/E normal in this era (and level of interest rates), a P/E in the 20s and 30s is only a slight premium. So should really good businesses trade for much higher? Probably, yes. But 60x for COST?

What would Munger do? Would he sell? Trim down? Over the years, BRK’s main holdings have been priced ridiculously high at times, and Buffett hasn’t sold out (he trimmed AAPL, though). I think he did say he regretted not selling KO when it was trading at over 40-50x P/E at one point. Is this a similar situation for COST now? I don’t know, but I will have to take a good look at COST and other holdings and maybe trim some things down. I always did say I will sell / adjust on valuation on a stock by stock basis, not on prediction / forecasting.

The market valuation is not where I would want to dramatically reduce exposure, though. As I said, that would happen much higher than here. It would have to be Tokyo 1989-like silliness. And in any case, it would be a stock by stock thing, not a market valuation vs. percent exposure question.

Punch Card Investing

So this whole idea of selling is a hard one. Professional asset managers tend to turn over their portfolios to keep their portfolios optimal in the sense of having the best companies at the most attractive prices at all times.

But what about the punch card investor? Some say that there are only a few true opportunities in a lifetime. But what if you find something great but it goes up a lot and gets really expensive. Then you sell. Then what? Most of the time, you will probably not be able to get back in. Just think of all the people who bought Apple when Jobs came back, and then sold out at a double or triple (I have no idea, actually, what the valuation of AAPL was at the time). It would have been the investment of a lifetime, but I do know people who didn’t go along for the whole ride.

Look at all the rich folks at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting. Look at BRK stock since 1970. How often did it look ‘overpriced’? What about the market? What if people sold out when they thought BRK was overpriced? Or the market? Would they be as rich as they are now? Probably not. Maybe there are some smart folks that got in and out of BRK over the years, but I would bet that the richest of them are the ones that just held it and did nothing.

I keep telling people this, but if you look at all the richest people in the world, a lot of them are people who held a single asset, and held it for decades. Look at Bill Gates. What if he was hip to value investing and knew more about stocks and values. He may have sold out of MSFT when it looked really overvalued. What about Buffett? What about Bezos?

A lot of the rich used to be real estate moguls, and I thought a lot of them were wealthy because real estate was not very liquid, so they had no choice but to hold on even in bad times. Stocks have what you may call the “curse of liquidity”. It’s so easy to say, holy sh*t, something bad is going to happen, and *click*, you can get out of the market. Back in the 90s, we used to fear a 1-800 crash; people will call their brokers’ automated trade execution lines, 1-800-Sell-Everything, and go “Get me out of the market!!! See everything NOW!!!”, and the market would not be able to open the next morning. Some of us truly feared that, and hedge funds talked about that sort of thing all the time. But you can’t do that with your house.

This is another reason I don’t post as much… Just like old people, I start to tell the same stories over and over. But one of my favorite ones is about a person I know who never really made all that much money, but was very frugal and saved and invested everything he can. And he never sold anything. He just held it and didn’t care. Once he studied something and bought it, that’s it. And one day, we went for a walk and he whispered to me that he was a millionaire. Well, I didn’t ask for proof, but I had no reason to doubt it. His losers? Didn’t matter. They became trivial and a non-factor in his portfolio. His winners? Of course, they get big. Huge. Let them run.

Now, this may not work for a professional fund manager, when you are trying to outperform every quarter, every year. But it can be fine for individual investors. You pick a stock, a bunch of them go to zero, say. And then a few of them just take off and make you a multi-millionaire. Do you care if you outperform every quarter? Probably not. That’s really a huge advantage for the individual investor. Time is on your side. You can afford to wait.

Conclusion

OK, so I had more things I wanted to talk about, but this is already getting too long, so I will end it here, and maybe put together another post soon.

But, I do acknowledge the market is getting a little pricey. Something that I didn’t feel for a long time, always disagreeing with people calling the market overvalued over the years. Of course, I have no idea where interest rates will go, so if rates get up to 6-7%, the market can obviously be very overvalued, or it can settle around here, or go back down to 4%. Who knows? I still tend to think it will be in the 4-5% range for a while. I was thinking about 4% as the normalized rate for a while, even when rates went under 1%. But I guess maybe it’s prudent to call it 4-5%. I know many are calling for much higher long term rates, so we’ll have to see.

But I don’t really make investment decisions based on the valuation of the whole market, so all of this is sort of like casual discussion / conversation… Something I would talk about in a bar, explaining to someone why I am not overly concerned of the market in general etc. But not something I would pitch as the ‘correct’ way to value the market in front of a bunch of professional investors. It doesn’t really matter all that much either way, if I am right or wrong. The idea is to make sure I do OK either way.

Great post. Thank you Brooklyn Investor.

Wise and sage advice.

Signed a simple Investor trying to get a little bit “smarter” every day.

Great post. I think looking at specific investments while weighing the economic backdrop serves well here. I also think that embracing recessions as the price to pay is essential. As you said, timing the market has ruined many careers.

Thanks for the post. I liked the line about posting less frequently as you get older because you end up repeating yourself. I find same when I have to write my annual fund letters. Good investing maxims dont change. Hard to keep it sounding fresh.

I have to nitpick the part about letting your winners run and losers fade… that I believe is the widely accepted coffee can portfolio idea but it is statistically just terrible. Most stocks do very poorly and so if you had a 100 coffee can portfolios for sure there will be ‘that guy’ the owned L’Oreal for 50 years so who cares if the rest went to zero but the odds are most of the 100 owned ‘not’ the winners and had very mediocre/less than tbill returns. Bessembinder study is good on this if you Google it.

Thanks. Your nitpick is understandable. Having told my friend’s story, I have to admit to my own story too. A while back, I too had a bunch of crap in my portfolio that I accumulated over the years and I remember one year, I just dumped everything that was ‘crappy’, subpar… And I only kept my best investments, and my performance improved dramatically since then. BUT, a lot of that is because my old stuff really were crappy. I had things in there that I bought, “just in case”, or with very little research, or an idea that went bad long ago etc… They weren’t the punch card-type, high quality businesses (they included closed-end funds, lol… at deep discounts, and other things with a decent idea/concept at the time that just didn’t pan out).

But if your picks are really the best of the best, and infrequent opportunities, then you may do better. You probably won’t find 100 things to buy in that case.

In any case, this is just sort of an illustration of Buffett’s favorite holding period, “forever”. And how hard it is to hop from one winner to the next one, and to do it consistently.

From December 1999 to December 2016 Walmart stock price was unchanged … PE went from 50 to 14. Maths of valuation compression even if underlying stock grows is almost as impressive as long term effects of compounding.

Bingo

This blog has changed the way I think about valuation. It’s just that it’s taken many years and posts for what you are saying to really sink in. As far as I’m concerned you can’t tell the story often enough.

Good read! Thanks for sharing!

I’d have to say both yes and no to some of these thoughts. In particular, the idea that riding through the tech crash or housing bust meant you were “OK” in the long run. Those events were so well telegraphed that staying in to ride them out was not very smart. If you stepped out and then back in – and I know people who did – them you made a generational step up in a short time.

At the tech crash time I was young and stupid and believed the ‘ride it out’ advice. I paid a huge price for that but learned a lesson., When the housing crash came – widely trumpeted in advance – I was smarter. If I knew in 2000 what I knew in 2007-2008 I’d have a multiple of the wealth I have now. Live and learn.

I bought my major holding in 1999 before the crash and rode it out. It is still my major holding, and it is now widely known as one of the best investments of the era. Won’t deny there is some luck involved. Still, the fundamentals were good before the crash, and recovery was a matter of time. My employer income of course allowed me to ride it out.

Great article thank you.

I guess the “answer” here is to simply apportion more of your portfolio to fixed income (re-invest dividends into FI or re-balance?). In the TINA era we’ve just exited I guess stressing about over/under valuation has been more of a thing as bonds were extremely poor risk/reward (I have allocated zero to bonds for years and am now buying – Howard Marks wrote a good note on this recently). Now it seems likely that FI and equities will be negatively correlated again in an equites bear market.

On self re-enforcing cycles this was thought provoking. The value of a stock does not reflect the value of the company, only the value of the marginal unit of supply of that stock. For example, if Elon Musk tried to sell all his Tesla holdings, he simply wouldn’t find a price anything like the current market price. With the rise of passive, if you have wealth (which generally increases over time due to GDP growth) blindly buying a basket of stocks (and because of said wealth increase the net flow is generally buying), it by definition blindly buys the marginal price without regard for value. Without active managers, you require the marginal stock to be released by somebody (company founders for example) but often this marginal supply is in short supply so you get these insane valuations (Tesla being a notable example but also NVDIA etc). Active managers themselves have become passive like for fear of underperformance also causing a shortage of the marginal unit. Hedge funds could provide the function by shorting but it’s very hard to short a cult like belief system (again Tesla, now NVIDIA). All of this is the self re-enforcing cycle you speak of and where it ends nobody knows, but low tide ultimately will follow a high tide.

look forward to your next article

I find your insight to be differentiated and quite valuable. I once ran a total return calculation on S&P 500 if you bought on day before crash of 1987 and short time afterward, I found that over a sufficient enough time period the average annual difference was nothing you would lose sleep over. I try to remember that when I feel things are jumpy. Thanks again for all your knowledge

Thanks for the post. I might add that markets outside the US (yes, they do still exist) on average look cheaper.

I also don’t mind if you keep posting the same stuff as long as you keep posting 😉

On a high value stock like COST, would a simple framework like if the stock dropped 50% and a ~30 PE ratio, would you buy more? This simple framework is based on the business not changing, only that valuation changed. Since Costco is a high quality business with pricing power and growth, I think the answer is yes. But is it at 35x? For me probably not, so 70x would be a good selling spot. And 80x cut to 40x, I wouldn’t buy at 40x.

Yeah, I would buy it back on big dips like that. I have done similar in the past with CMG, which I have owned for many years. But I did dump a lot of it when it traded above 70x P/E, and then got back in when the food-poisoning thing hit them etc.

What scares me about valuations like Costco are the premiums for consistency. Yes, it’s a good business with strong management, but there are better businesses like MCO and V trading at 46 and 35 P/E. Reliability premiums can be fragile, as we see with Hershey’s dropping from a 30 P/E to 18.

Great point

I never realised “the market” consists of the cited tickers plus BA.

Yeah, well, as flawed as the Dow 30 is, in the past, it correlated highly with the S&P 500 index. Recently, we have more days with the Dow tanking and S&P up and vice versa, but over time, the correlation has been pretty high. So, instead of looking at the P/E ratios of each of the 500 stocks, I used to just, every now and then, look at the 30. Not perfect, or great, but just one of the many things I used to look at regularly…

“Look at Bill Gates…” don’t forget Steve Ballmer!!

Excellent piece, thanks!

Your conclusion lines up with other research indicating that apparent overvaluation by itself isn’t a sufficient reason to sell. Sometimes the market is simply anticipating an improvement in earnings. Other times, there’s a macro backdrop influencing asset allocation decisions. In recent years, for example, there have been arguments to be light on bonds given that both low rates and the view that some inflation may be needed to work down real debt levels.

I started my investment career about 15 months before the 1987 crash and it was quite a shocker for someone who had only been watching markets for ~7 years. At the time, Quotron machines were the primary terminals for looking up prices and I remember some colleagues gathered around as the index decline approached 100, wondering if the coders had allowed for a three-digit decline in their formatting rules.

As you note, getting in and out of the market at the best times is difficult. I think there are at least a couple of reasons for that:

1) Doing so requires not just one good decision, but two.

2) If you’re wrong, you must recognize that promptly and reverse course

3) A very small percentage of days (I want to say 1%?) account for the vast majority of stock appreciation. If you miss the bottom and anchor on those prices, you’re likely to miss several of these days at key inflection points.

With regard to when to sell a particular stock, I try to sort these decisions into two buckets:

1) If I believe the company has a long runway of growth well above the average for the economy, I’m unlikely to sell even when valuations get quite high — unless I have a more compelling alternative competing for capital.

2) If my investment was based largely on valuation and I see more normal rates of growth ahead after the business has recovered from a short-term challenge, I think about the degree of overvaluation relative to tax impacts(*)

(*) Perhaps considering a sale is appropriate when the stock is overvalued by: a) my marginal cap gains tax rate, plus b) an overvaluation factor tied to the volatility of the stock and valuations on alternatives in the market. Factor (a) ensures you can have the same level of equity in whatever entity into which you plan to redeploy the capital (and, for income-oriented investors, a similar level of capital with which to generate dividends).

Sounds good to me. Thanks for dropping by!